Adventures in Belfast: Child’s Play

If you get a chance, next time you’re in Belfast, visit the historic and colorful Falls Road.

The Falls was a powerful IRA-stronghold during the Northern Irish Troubles, as its many murals will attest. The larger than life, multi-colored paintings commemorate different events in Irish republican history, such as the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin and the loss of 10 IRA volunteers during the 1981 hunger strikes.

The North is no longer so sharply divided between the two camps of Protestant British and Irish Catholic. While still proud of its roots, the neighborhood is now far more open to “outsiders” and is known as a culturally vibrant, friendly, even touristy part of the city.

The story below is taken from Adventures in Belfast: Northern Irish Life After the Peace Agreement, a book that chronicles life in Belfast, past and present. This excerpt recalls the days of the Troubles from a man who grew up on the Falls in a proudly republican family.

![]()

From Chapter 5 – Child’s Play

I asked Padraig if he would give me a tour of the Falls Road as he’d grown up there. It would be a chance to hear a nationalist describe what their side of the Troubles had looked like. Soon after, on a windy day in February, we spent four hours wandering that area. We walked through the upper and lower Falls Road, the Andersonstown area, known as Andytown, and the Turf Lodge area.

Walking into the area from the city centre, Padraig explained that the area had had, for a long time, the effect of a psychological barrier for Catholics, who felt they were not entitled to that part of town. Then he pointed out a long metal wall with barbed wire on the sides and top—the famous peace line.

“All the locks are on the Protestant side,” he said, so the cops could come and go as they liked, from the Protestant neighborhoods. On the other side lay the Shankill, an area Padraig has never wandered much. Except once when he was a teenager, when he’d been smoking hash and was stoned out of his head. Of course some guys saw him, knew he didn’t belong there and starting running after him—lobbing bottles at him as he scaled up the wall and over the jagged top of the fence, tearing his jeans.

Then he came down on the Falls side, and a man walking his dog started nervously and started running away from him, thinking he was “a Prod” from the Shankill.

He laughed remembering it. “I told him, ‘It’s okay, it’s okay! I’m a taig!’

“Isn’t that term always an insult?” I asked.

He shrugged—it was harmless enough when a Catholic was using it lightly—and explained that “taig” [pron. TAYG] came about because so many Irish men were called Taidgh [pron. Ty-EEG] that the English started calling all Irish that, and due to English pronunciation, it became “taig.” An ethnic slur, a little worse than “mick” or “paddy.”

We walked past where the infamous dilapidated Divis Flats public housing used to be—only the tower now remained, with Army technology atop it in the form of what looked like satellite dishes and other technology.

“Divis Tower is still used by the British army—” Padraig began.

“As a security post,” I said automatically, from my collection of gathered facts.

He smiled and asked, “Security from what? Security for who?”

A mural on the 'International Wall' in west Belfast. During the Troubles, city buses stopped running in west Belfast, so the local people pooled their money, went to London and bought taxis to be used locally. Sinn Féin politician and former Provisional IRA volunteer Martin Meehan (1945-2007) is also remembered here. He was the first person to be convicted as a Provisional IRA member and spent 18 years in prison during the Troubles. Photo Wikimedia Commons: Ross

We walked up the lower Falls, past the Sinn Féin office and bookshop, St. Dominic’s School, and a beautiful old church once used for Presbyterian services, now a landmark west Belfast building called An Chultúrlann (Cultúrlann McAdam Ó Fiaich). It had become an Irish-language arts and performance center in 1991, named in honor of Roibeard McAdam, a Presbyterian businessman who led the revival of Irish-language speaking in nineteenth century Belfast, and Tomás Ó Fiaich, a twentieth century Irish-language advocate.

We resumed walking, and Padraig commented that much of Irish culture had been lost over the last century.

“Why do you say that?” I asked. “Because you don’t hear people speaking Irish on every corner as often as you hear English?”

“Do you not think that’s a significant cultural loss?” he asked. I had to agree that it was.

As we walked on, Padraig mentioned Bombay Street, and asked did I understand why all of its houses had been burnt down in 1969. I knew little of the exact events, only that 1969 was a seminal year that had brought ongoing clashes among Catholic civil rights activists, the RUC and Protestant loyalists. Padraig explained that the civil rights activists were met with violent resistance from loyalists, backed by the RUC.

One August day in Derry, the RUC moved to disperse nationalists who were protesting a loyalist parade, pushing them back into their Catholic neighborhood, called the Bogside. When the police attempted to enter that neighborhood, all hell broke loose in a three-day riot involving hundreds of police officers and thousands of Catholic residents.

Nationalists throughout the North were called upon by the Civil Rights Association to support the Bogsiders. Demonstrations turned to riots, particularly in Belfast. Barricades were set up between neighborhoods, and nationalists fought the RUC with rocks and petrol bombs. Then guns were brought in, on both sides. The IRA, at that time limited to only a few gunmen, exchanged fire with RUC officers and loyalist gunmen, trying to hold off further incursions into their west Belfast neighborhoods. But loyalists drove their way into the Catholic neighborhood, burning all of the homes on Bombay Street and some on the neighboring streets as well.

We next stopped at one corner and Padraig pointed out a building where he and a few of his brothers witnessed something terrible one day, in a barber shop, when he was four or five years old. The IRA was positioned on the next corner, and British soldiers, always called “the Brits,” were positioned across the street from them. Shooting began, then “the Ra” launched a missile at them.

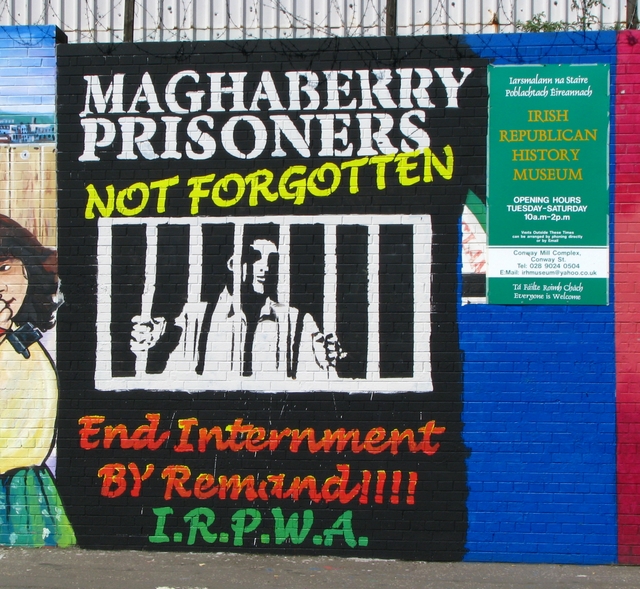

Part of the 'International Wall,' this mural depicts Irish Republican prisoners in jail. They were supported by the IRPWA (Irish Republican Prisoners Welfare Association). Photo Wikimedia Commons: Ross

“All I saw was legs flyin’ everywhere,” he said. “The Brits weren’t expectin’ that!”

I was horrified that he’d had to witness that at such a young age. The street where it occurred was Beechmount Avenue. The street sign showed “Beechmount” crossed out and “RPG” written above “Avenue.”

“Rocket-propelled grenade,” Padraig explained.

From there we walked west up a hill, past more of the sort of street art Belfast is famous for: pro-IRA graffiti and republican murals, some commemorating historical moments like the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin, and the IRA hunger strikers of the early 1980s.

It had been hard for Padraig growing up. His mum was a political activist on unemployment benefit, supporting six kids on her own after her husband died.

Because of his mother’s feminism, Padraig had been raised with a very different outlook than that of the men around him. He had an unusual awareness of the world. His mother would tell him when he was a boy, “Women get the short end of the stick in this world.” That had shaped his thinking early on.

I asked what it was like growing up in west Belfast “while the Troubles were on,” as they say in the North.

“My earliest memory of the Troubles, when I was very young,” he said, “would have to be soldiers coming into the house, basically throwing my ma around the room, throwing all our toys out the window. Just destroying the house. I would have been probably four or five. As far as I could tell, they were just big, bad, bad men. That’s all I saw them as. I didn’t see them as soldiers or anything like that. I just saw that there was a sort of dark cloud around them. And they had a bad intent coming into the house. They didn’t have any respect. Whenever they were around, it was like the clouds came and the sky was dark all around. And that sounds a bit over the top, but as a kid, that’s how I remembered it.

“There used to be riots around our area—quite a lot. I remember once all the children had built a sort of barricade. It was sort of the culture of the entire west Belfast, that whenever you heard the women banging the bin [aluminum garbage can] lids on the ground, it was a warning to the Ra that the soldiers were coming in.

This is an anti-war mural, based the painting Guernica by Pablo Picasso, which depicted the 1937 Nazi bombing of a town in Spain. This version was painted by Danny Devenney, a renowned Irish nationalist painter, and Mark Ervine, son of the late Progressive Unionist Party leader (and former loyalist paramilitary) David Ervine. Photo Wikimedia Commons: Ross

“The barricade was on the entrance to our estate from the main road. We had built a barricade with stuff, me and my friends. There was all these small planks of wood with nails coming out of them. Don’t know where we would have got them from, but we would’ve nailed the nails through the planks, right? And we’d have them all set up one side of the barricade, so if someone hopped over the side, it’d burst their tires. And it did happen—there was some degree of success with that,” Padraig said, and laughed at the memory. He was about six or seven at the time.

“We kids would go around with pieces of metal or wee poles that looked like machine guns or whatever when we played soldiers. I remember the cops would always take them off us—‘That looks like a gun! That looks suspicious, so it does!’ And they would take it off us. I remember being absolutely devastated by that.

“I remember going on the marches was quite a regular thing for us as children. A lot of them, I wouldn’t know the specifics of them, being a kid, but I remember a lot of them would have been for women’s rights, and for the women in jail. There were a lot of marches we went on that had to do with what was happening with the women in Belfast or all over the North even. I remember going down to protest at the site of the Armagh jail, and basically protesting the conditions that the women were kept under. They were deprived of exercise and washing facilities. A lot of them would have been strip searched quite often, by men. This happened to my mother also, on a number of occasions, when she was put in jail for one reason or another.

“But the marches—the one that stuck out in my mind the most—my mum wasn’t there—I think she was in jail. My brother was about three, and we were walking along the front of the march with our aunt. We were marching down the Falls, and I remember that every march we were on, we were absolutely surrounded by police and army, helicopters flying above us.

“So we got down to the bottom of the Falls and we went through Divis Street, and we were supposed to march on City Hall. I knew that Catholics were not allowed to march on City Hall. I don’t think the marches were necessarily republican. I think the marches were just about the treatment of Catholics. But we weren’t allowed to march on City Hall at that stage—definitely not.

Children playing in the Falls Road area, 1981. Photo Wikimedia Commons: Jeanne Boleyn

“Castle Street was the old barrier for the Catholic people, psychologically. It was right along Castle Street where the Brits had set up their cordon. And I remember it was all barbed wire and they were all standing behind it with their guns and their riot shields and everything on. And as we turned left off Castle Street, I just remember a lot of soldiers running up from the sides, and they just opened up. There were rubber bullets, because I remember these big black bullets flying past me and bouncing off the ground. And I ran over to the wall and I started crying—I remember people running everywhere. I was about five, and I got separated from my auntie.

“These houses are still there—this part of west Belfast was called the Pound and the Pound Loney. I remember I ran, and there were soldiers all around me. I remember being really, really scared, that everybody had left me, and they had left me with these soldiers that were going to shoot me. But they didn’t pay any attention to me, and I ran off and all the way up through the streets, and as I got up to the top, there was a lot of the younger fellas that turned round and started throwing stuff back at the Brits.

“Some woman just grabbed me into her house and put me in behind her front door. I remember standing behind her front door, and all the shouting and screaming, and bottles smashing, and all the gunfire all round. And I honestly can’t remember what happened after that there. But somehow I was located again by my aunt or whoever was with her.

“See it was a funny sort of mixture for me, growing up in west Belfast. In one sense, strangely enough, my childhood was quite exciting—in some ways the best time of my life, which sounds strange. But I think it was the real sense of community—I had lots of friends and lots of places to go. And even though, looking back, the Troubles was a bad thing to be around as a child—as a child, I thought it was great. It’s not how I feel now. But I remember, I wasn’t even afraid half the time, I was just fascinated by all this stuff that was going on. So in one sense my childhood was a lot of fun and excitement, and in another sense I remember that definitely there was a lot of darkness around. The adults were all afraid. There was a lot of seriousness among the adults, plus the fact that most people were bloody alcoholics as well, you know?

“A lot of people are screwed up from the Troubles. You wouldn’t believe the amount of children that went into [state-run] care over that time. A lot of people would have been killed, some of them would have volunteered [joined the IRA] or had to go on the run. Or some would have just hit the drink because of what had happened. But everyone was affected in one way or another, on all sides. I think that is the reason the IRA decided to take the war over to England, because everybody here was being affected by it, so they decided to take it to them—the main perpetrators weren’t being affected by it at all. So there was the paradox for me, for my childhood. The adults were afraid, all the time.”

“Did you think then that you would grow up to be afraid all the time?” I asked.

“I did,” he said. “A good part of my life. But in a way that was normal for us. When you’re used to something, you just think that’s the way it is. It’s like a lot of working class communities, they’re used to poor education and they’re used to in some respects, a lower quality of life. So they think abuse is normal, violence is normal. And that was what it was like for me.”

Adventures in Belfast: Northern Irish Life After the Peace Agreement (2014) is now available in the Kindle store. You can Download it for free now through February 28, 2014, on Story Cartel -- then post a review on the book’s page on Amazon to be entered to win one of three $10 Amazon gift certificates.

More Adventures in Belfast Goodness: an excerpt from Chapter 4: Tempestuous Witch.

Caroline Oceana Ryan is an author and freelance writer, and Northern Ireland Editor for Wandering Educators. She blogs about personal growth and bullying prevention at www.carolineoceanaryan.com.

Excerpts from Adventures in Belfast: Northern Irish Life After the Peace Agreement Copyright 2014 Caroline Oceana Ryan. All Rights Reserved.

No part of this content may be reproduced in any form whatsoever without written permission from the author.

Belfast's living history: the days of the Troubles from a man who grew up on the Falls in a proudly republican family.

Posted by: Caroline Oceana Ryan