The approximate 6,000 ships that have succumbed to raging storms attest to the power of the Great Lakes. As I traveled, writing and compiling information for my three-volume travel series, Exploring Michigan’s Coasts, I heard or read the tales left behind by those ill-fated ships. They add a somber, but compelling backdrop to Michigan’s waterways.

The Carl D. Bradley was a self-unloading Great Lakes freighter that sank at 6:00 p.m. on November 18, 1958, during a gale-strength storm in northern Lake Michigan near Gull Island. That dreadful night, 60-mile-an-hour winds and 40-foot angry waves claimed the lives of 33 of the 35 crewmen. Two men were found alive the next day.

A painting of the Steamer Carl D. Bradley battling a storm on Lake Michigan on November 18, 1958. The painting by Ken Friedrich, a former Bradley crewmember, depicts the boat breaking in half. Only 2 of the ship’s 35 crewmembers survived the sinking. Photo Presque Isle County Historical Museum

Although the ship went down in Lake Michigan, the Bradley’s ties were clearly to Rogers City and Lake Huron. Of the 33 lost, 23 were from Rogers City, and most of the others called nearby cities and villages home. It was said that you couldn’t walk a street of Rogers City without passing the home of a widow.

The Bradley remains the largest ship to sink in Lake Michigan. When launched in 1929, she was the most powerful ship on the Great Lakes, but she proved no match for the mighty lake. Most of the deceased were of Polish descent, many knew each other’s families, and many were related. The ship’s cook often served the sailors kielbasa purchased from a neighborhood market in the Polish Town section of Rogers City.

Ship Captain Roland Bryan was an outsider. He still made his off-season home in Loudonville, New York, but he had been sailing with the Bradley Transportation Line for twenty-four years, and even when his crewmen sprinkled their conversation with Polish, he usually understood.

The night the Bradley sank, she was returning empty after delivering her last shipment of limestone for the 1958 season to Gary, Indiana. It was a happy day. Captain Bryan had a sweetheart in Port Huron. For the eight-month shipping season, he rarely saw her unless he picked up a load in Lake Huron and could blow his horn in salute as he passed by. In a couple more days, he would see her again. He wished the weather forecast was less ominous, but he had endured many storms in his career. He knew if he delayed leaving Gary, his entire crew would be unhappy. They, too, wanted to get back to families and loved ones.

The Bradley was in her thirty-first season, and she was due for inspections; inspections that would have revealed she needed work. But winter was coming and that was the time for repairs.

Captain Bryan headed northwest, seeking protection from the winds along the west shore of Lake Michigan. The next day the weather worsened. It might not have been the worst storm to ever hit Lake Michigan, but it was too much for the Bradley.

The ship’s Mayday signal was picked up at the Charlevoix Coast Guard station at 5:30 a.m. on November 18. The message described the Bradley’s position twelve miles southwest of Gull Island. The radio operator listened to the crewmen shouting, “Run, grab life jackets. Get the jackets.” Then came another, “Mayday. The ship is breaking up.”

It was the terrified voice of Elmer Fleming sending the Mayday calls. He and Frank Mays, the two survivors, were found the next morning in the life raft they shared. Two additional crewmates had clung to the raft until a huge wave flipped the frail vessel, drowning Dennis Meredith in the brackish water. Fleming, Mays, and Gary Strzelecki managed to climb back aboard. Just after dawn, Strzelecki declared he had enough. The men were sending up flares but had no reason to believe they had been spotted. Strzelecki jumped off the pontoon-like raft and began swimming toward shore.

Fleming, too, doubted his Mayday signals had been heard. He was a happy man when he saw the Coast Guard rescue ship Sundew headed his way an hour after his crewmate had given up and begun swimming to his death. Mays admitted to doing a lot of praying that night and said he had never been so cold in his life. His numb hands did not want to continue hanging on to the ropes attached to the raft, but his mind did not want to let go. Ice formed on the hair and clothing of the two survivors who endured fourteen hours before their rescue.

When news reached Rogers City that two survivors had been found, the city rejoiced, hoping the remaining thirty-three missing were also alive. Instead, search vessels began retrieving bodies. The survivors gave the following accounts: Mays was working below deck when the ship started breaking up. He was thrown into the water as the Bradley capsized. He had the good fortune to surface a few feet from the raft and was able to get aboard. From there he watched the stern of the ship go straight down. An explosion followed as the ship slipped under, and water hit the boilers.

Carl D. Bradley Pilot House. Depth here is approx. 315 feet. Photo Wikimedia Commons: John Scoles/John Janzen

Fleming had been in the pilothouse with the ship’s captain when he was first alerted to trouble by a loud thud and an alarm. When he saw the stern sagging, he knew it was bad. Instinctively, he realized the ship was going down. He stepped out on deck as the Bradley rolled to its side, throwing both him and a raft into the water.

While many casualties on shipwrecks from the 1800s and early 1900s were attributed to lack of lifeboats, lack of life jackets, and the lack of radio communication—all of which were no doubt important in saving lives—Lake Michigan made it very clear there were times when even those were not enough.

The weather wasn’t determined to be the single cause of the wreck. The Bradley was hampered by structural failure from the brittle steel used in her construction.

Two museums in Rogers City provide history and artifacts of the wreck of the Carl D. Bradley. Presque Isle County Historical Museum, 176 West Michigan Avenue, (989) 734-4121. Presque Isle County Historical Museum showcases local history. The museum is comprised of two buildings, the 1914 Bradley House and the Henry and Margaret Hoffman Annex across the street. The Annex was acquired in 2011.

The craftsman-style Bradley home was built in 1913 and 1914 by George Radke and was sold in 1915 to Carl D. Bradley. Before moving in, Bradley undertook extensive changes to the almost new structure. The renovations included a new kitchen, maids’ quarters, second-floor dormers to increase the upstairs space, a two-car garage, and landscaping. With alterations completed, the three members of the Bradley family shared a seven-bedroom, four-bath home with three sun porches.

In 1920, Mr. Bradley became president of U.S. Steel and was in charge of the company’s fleet, made up of three freighters—the Calcite, the W. F. White, and the Carl D. Bradley. The fleet operated as the Bradley Transportation Line.

The museum’s main house includes a General Store Room (originally a guest bedroom) that houses many items that would have been found in an early general store. There also is a Native American Room, a Millinery Room, and a room with pioneer tools.

Through its exhibit, 50 Years—Never Forgotten, the museum pays tribute to the lives lost when the Carl D. Bradley went down.

The Henry and Margaret Hoffman Annex houses a number of additional exhibits, the museum’s gift shop and bookstore featuring many local authors (See A Book with Ties to Rogers City), and genealogical records.

Great Lakes Lore Maritime Museum, 367 North Third Street, (989) 734-0706, tells the story of Rogers City’s port activities and the seafarers of the Great Lakes. Like the County Historical Museum above, this small museum pays homage to the lives lost when the limestone carrier Carl D. Bradley sank in a Lake Michigan storm. The guides explain the artifacts and may share some of the personal stories of the men who perished in the greatest tragedy to ever hit Rogers City.

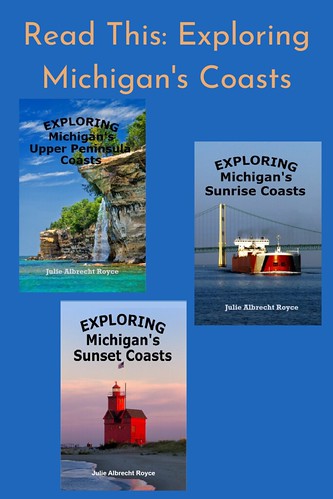

Click through to read excerpts from Royce's three books exploring Michigan's coasts:

Julie Albrecht Royce, the Michigan Editor for Wandering Educators recently published a three-book travel series exploring Michigan’s coastlines. Nearly two decades ago, she published two traditional travel books, but found they were quickly outdated. This most recent project focuses on providing travelers with interesting background for the places they plan to visit. Royce has published two novels: Ardent Spirit, historical fiction inspired by the true story of Odawa-French Fur Trader, Magdelaine La Framboise, and PILZ, a legal thriller which drew on her experiences as a First Assistant Attorney General for the State of Michigan. She has written magazine and newspaper articles, and had several short stories included in anthologies.

Books available on Amazon.

Ship photo in the Public Domain.