The approximate 6,000 ships that have succumbed to raging storms attest to the power of the Great Lakes. As I traveled, writing and compiling information for my three-volume travel series that explores Michigan's coasts, I heard or read the tales left behind by those ill-fated ships. They add a somber, but compelling backdrop to Michigan’s waterways.

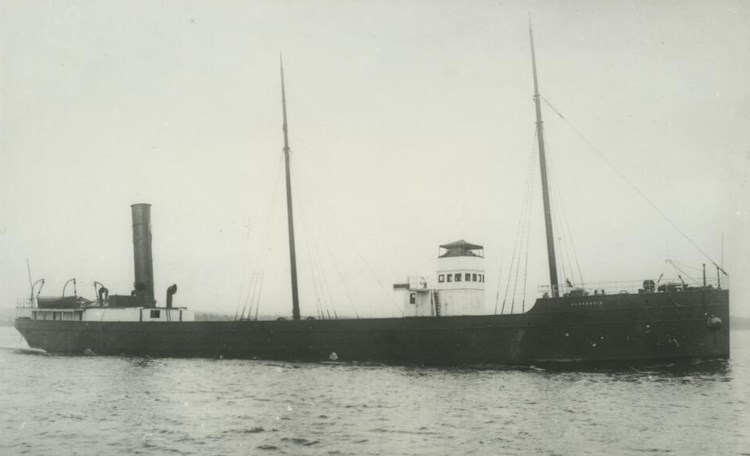

The Ghost Ship S.S. Bannockburn started her career without a great deal of hullaballoo. The steel-hulled freighter was a cargo ship whose duties took her through the Welland Locks, around the St. Lawrence Seaway, and into the Great Lakes. Little did she know that she would end her existence—or what we know of it—nicknamed the Flying Dutchman of Lake Superior. The Flying Dutchman was a legendary ghost ship with a reputation for never making it to port. It was doomed to sail the oceans forever.

The Bannockburn was a workhorse that carried 1,500 tons of freight. On November 20, 1902, she left Fort William headed downbound for Georgian Bay in Lake Huron. The oldest crewman was 37. Most of the remaining 19 were between the ages of 17 and 20, and the youngest was a mere 16 years old. Many teenaged boys signed on for a good paying job that promised independence with maybe a touch of adventure. Ship owners weighed experience against cost, and often hired inexperienced youth because they worked cheap.

On her last trip, the Bannockburn carried 85,000 bushels of wheat. She ran aground before she made it into open lake. She turned back to port, but careful examination found she had sustained only minimal damage. Declared sound, she resumed her voyage the next day.

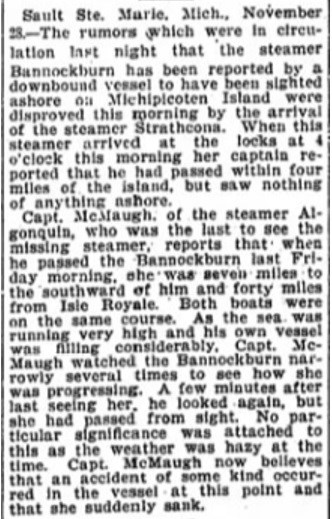

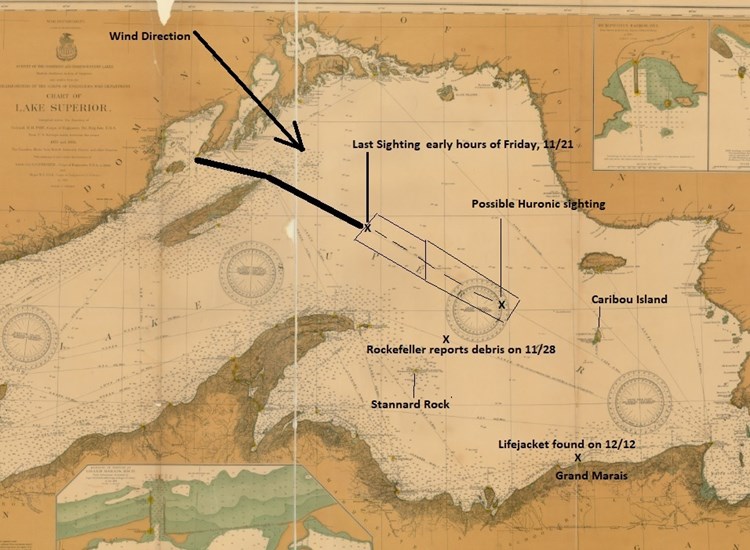

Captain James McMaugh of the upbound freighter Algonquin sighted the Bannockburn seven miles southeast of his position on November 21. He believed the Bannockburn was about 80 miles off Keweenaw Point and 40 miles off Isle Royale. Captain McMaugh identified the Bannockburn several additional times over the next few minutes. His last attempt to spot her was unsuccessful, a fact he attributed to the pea soup murkiness around him. He thought no more about it, assuming the Bannockburn had been swallowed by the fog.

Algonquin–last ship to see Bannockburn alive?

The weather turned colder and violent. Spitting snow and driving ice crashed down on Lake Superior. At approximately 11:00 p.m., the passenger steamer Huronic, also upbound on the lake, reported seeing lights on a ship she passed during the blizzard. The Huronic saw no signals of distress, and the two ships passed without incident or closer contact. The Huronic believed, based on the ship’s shape and the patterns on her side, she had encountered the Bannockburn making good speed in the direction of the Soo Locks. The Bannockburn never arrived.

On November 25, the steamship John D. Rockefeller sighted a debris field near Stannard Rock Light. The lighthouse, dubbed the loneliest place in America, is a spooky place in its own right.

No one knows what foul circumstances could have been witnessed from that point on the night the Bannockburn is believed to have disappeared. But the Bannockburn was only ship missing, and the only ship whose remains that debris could be. Five days later, the Bannockburn was officially declared lost. Several days after that, a cork lifejacket from the missing ship washed ashore near Grand Marais Lifesaving Station.

One theory of what happened to the Bannockburn the night of her demise suggests that she tangled with a treacherous reef around Caribou Island. The Caribou Island lighthouse had been intentionally turned off on November 15, the assumed close of the shipping season—a time for giving over the lake to the witches of November. Unfortunately, several ships remained on the great inland seas. They were in desperate need of a shining light. Perhaps the first clue the Bannockburn’s hapless captain got that the Bannockburn was in deathly danger was the sickening sound and lurch as his hull crashed over the reef. From there he may have limped close to Stannard Rock.

Other than the one life jacket, the remains of the ship have never been found.

An odd and bitter story related to the tragedy involved the manager of the Transportation Company that owned the Bannockburn. Caving in to the demands of loved ones wanting word of the ship’s fate, he claimed he had received a message that read: "The steamer Bannockburn has been located on the north shore of Lake Superior opposite Michipicoten Island. Crew safe." The manager later admitted this story was based on a rumor that the Germanic, another freighter, had seen the Bannockburn safely anchored there. Perhaps that was the mere sighting of a ghost ship.

Why one ship develops the reputation of a ghost ship, while hundreds of her sister ships rest in peaceful obscurity, is not always easy to explain. Sometimes there is a detail or two that tugs at our heartstrings. There is usually the added mystery that the ship remains lost. In the case of the S.S. Bannockburn, maybe the Great Sweetwater Seas simply wanted their own version of the Flying Dutchman—and the Bannockburn got the dubious honor.

On inky black nights when no distinction can be drawn from where the sky touches the water, sailors claim to see the Bannockburn with a crew of hollow-eyed skeletons on deck.

Just stories passed along and born of a bored sailor’s imagination? Maybe and maybe not. Some of the tales are repeated by seamen who are respected for their no-nonsense approach to sailing—men not known as storytellers. For 119 years, there have been reports that on some nights before a major storm, ship crews see the S.S. Bannockburn sailing, skimming, scudding by in a fog or mist, maintaining the course it has held for 120 years.

Regardless of whether a sailor believes the tale, it takes the staunchest of heart to ignore a proclaimed sighting. That has to be a bad omen.

Click through to read excerpts from Royce's three books exploring Michigan's coasts:

Julie Albrecht Royce, the Michigan Editor for Wandering Educators recently published a three-book travel series exploring Michigan’s coastlines. Nearly two decades ago, she published two traditional travel books, but found they were quickly outdated. This most recent project focuses on providing travelers with interesting background for the places they plan to visit. Royce has published two novels: Ardent Spirit, historical fiction inspired by the true story of Odawa-French Fur Trader, Magdelaine La Framboise, and PILZ, a legal thriller which drew on her experiences as a First Assistant Attorney General for the State of Michigan. She has written magazine and newspaper articles, and had several short stories included in anthologies. All books available on Amazon.

Help promote Michigan. Books available on Amazon.

Photos in the public domain or via https://www.shipwreckworld.com/articles/gallery/20186/10569