The approximate 6,000 ships that have succumbed to raging storms attest to the power of the Great Lakes. As I traveled, writing and compiling information for my three-volume travel series, Exploring Michigan’s Coasts, I heard or read the tales left behind by those ill-fated ships. They add a somber, but compelling backdrop to Michigan’s waterways.

The J.H. Hartzell shipwreck wasn’t extraordinary when compared to the thousands of her sister ships that have succumbed to the savage power of the Great Lakes—at least not if you look only at the facts reported by government agencies. The Hartzell was a wood schooner, built in 1863, and sunk on October 16, 1880, one mile south of Frankfort. She was carrying iron ore bound for Frankfort from L’Anse. All but one of her crew of eight was rescued from the rigging. That one fatality is the story that makes this wreck tantalizingly wicked.

The tragedy occurred nearly a century and a half ago, but the tale is still told, and the ship’s remains still litter the lake’s bottom near Frankfort. It’s rarely a warm, balmy summer night when violence strikes. The lake stores up her anger to vent when the weather turns blustery cold. On that particular night, the sole victim was a woman who died lashed to the sinking ship’s mast.

Townspeople and surfmen from the nearby lifesaving station labored under punishing conditions for more than 12 hours. In that time, they saved the seven men aboard. The solitary woman, cook Lydia Dale, remained beyond the rescuers’ reach. The men, as they were dragged ashore, told the rescuers that Lydia was already dead. The mystery that remains is, was she?

The Hartzell arrived at Frankfort at around 3:00 a.m. Captain William A. Jones explained that he decided to anchor offshore and wait until daylight to enter Frankfort’s harbor. That was a mistake. At dawn, the winds shifted and the pleasant, late fall weather turned nasty. Hail, snow, and rain whipped across the water and tormented the crew. Captain Jones and the six men with him let both anchors go and tried to turn the Hartzell away from the gale, “but in the growing fury of the wind and sea, the vessel would not obey her helm and began to drift in.”

The vessel broke up. The cook was reported to be seriously ill. The crew climbed 50 feet, and with four men, boosted the heavyset woman to a platform they created. They said they wrapped her in blankets covered in wet canvas cut from the topsail. The ship’s perilous situation was noted, and local citizens built a big fire on the beach. Using driftwood, they spelled out “Life Boat Coming.”

By the time the lifesaving crew reached the shoreline, only half of the schooner was above water. Local farmers and other townspeople helped as the surfmen started rescue attempts. A surf car was sent to the ship, and the first of the crewmen reached shore. They were asked about the woman and gave evasive answers, saying she’d be in the next run of the surf car. She wasn’t. That trip carried the second mate and captain. The third and final time the car went out, the rescuers gave it plenty of time in case loading the woman was a difficult task. It was growing dark, and they finally gave the order to bring the car back.

A dozen men went into the surf to haul in the car. When they opened the hatch, the last two men were inside. But not Lydia Dale. The two men aboard insisted the cook was dead—stiff as a board. It was too dark to attempt another trip out, and the lifesaving station team decided they’d wait until morning before undertaking further rescue attempts.

The next day, the schooner’s mast was gone. And with it, supporting evidence of what had happened to Lydia Dale aboard the Hartzell.

The town engaged in heated arguments of whether Lydia Dale was already dead when the men deserted her and climbed into the rescue car, or whether they mercilessly left her to die alone. The coroner settled the argument when he reported that Lydia Dale died of drowning—she had been left aboard while she was still alive and died later when the ship’s mast fell into the lake. The Hartzell’s crew was not there for the inquest. They had already left town.

Want to see more? Here’s a documentary about this shipwreck!

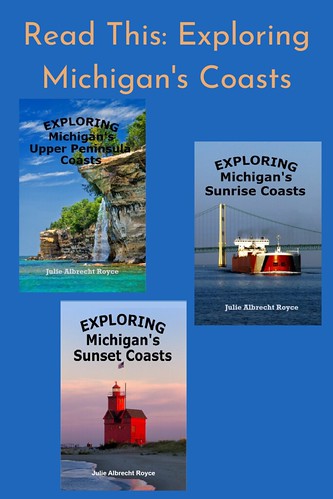

Click through to read excerpts from Royce's three books exploring Michigan's coasts:

Julie Albrecht Royce, the Michigan Editor for Wandering Educators recently published a three-book travel series exploring Michigan’s coastlines. Nearly two decades ago, she published two traditional travel books, but found they were quickly outdated. This most recent project focuses on providing travelers with interesting background for the places they plan to visit. Royce has published two novels: Ardent Spirit, historical fiction inspired by the true story of Odawa-French Fur Trader, Magdelaine La Framboise, and PILZ, a legal thriller which drew on her experiences as a First Assistant Attorney General for the State of Michigan. She has written magazine and newspaper articles, and had several short stories included in anthologies. All books available on Amazon.

Help promote Michigan. Books available on Amazon.

Photos via http://betsiecurrent.com/index.php/resurrecting-shipwreck-tale-125-years/