Shipwrecks of the Great Lakes: The Phoenix

The approximate 6,000 ships that have succumbed to raging storms attest to the power of the Great Lakes. As I traveled, writing and compiling information for my three-volume travel series, Exploring Michigan’s Coasts, I heard or read the tales left behind by those ill-fated ships. They add a somber, but compelling backdrop to Michigan’s waterways.

Illustration of the steamship Phoenix which burned on Lake Michigan November 21, 1847. Photo Wikimedia Commons, in the public domain

The Phoenix sank in Lake Michigan on November 21, 1847. In medieval times, the mythical phoenix was common in Egyptian, Asian, and Greek culture. When the eagle-sized phoenix grew old, it made a nest and set it on fire. The flames consumed the bird, which was then reborn from the ashes.

In a stroke of macabre irony, the steamer Phoenix, bearing the name of that mythical bird, was one of the first vessels to burn on the Great Lakes—but nothing rose from her smoldering ashes. At the time of her demise, the Phoenix was still in her infancy, a mere two years old.

Almost all westbound travel in those days was by boat through the Great Lakes. The wave of immigration headed westward caused ships to stretch their capacity. On her final voyage of the season, the Phoenix was packed to bursting with about 70 Americans and more than 200 Dutch immigrants. Only a handful of the latter had cabins. The remaining passengers wedged into steerage or found space on deck. Even the cargo hold was crowded beyond comfortable capacity. The crew of 29 looked forward to this last trip of the season, but their anticipation was tempered by the knowledge that late November voyages were fraught with danger.

The Phoenix departed Buffalo on November 11. On the 13th, she was still in Lake Erie. A week later, on Saturday, November 20, the Phoenix arrived in Manitowoc, Wisconsin, with her cargo of coffee, molasses, sugar, and hardware destined for that port. Ugly weather forced her to remain in harbor for several hours after the cargo was removed. About 1:00 a.m. on November 21, Captain Sweet gave the order to continue the voyage that was intended to end at Chicago. He expected to make the next port of his journey by daylight.

Flames were noticed over the boiler on the underside of the deck at 4:00 a.m. About the same time, fire sprouted from the ventilators that moved hot air from the boiler room. Crew members, with the assistance of some passengers, immediately started fighting the blaze. Bucket brigades were set up, but the fire had a good start and raged out of control in spite of the efforts.

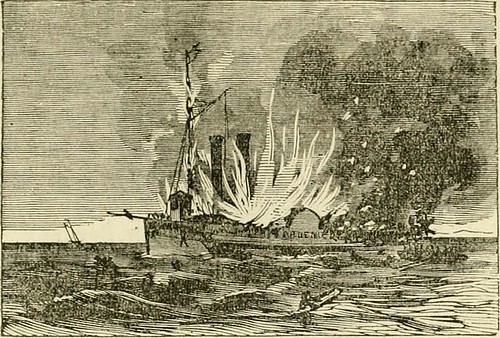

The burning of the Phoenix on Lake Michigan in 1847, James T Lloyd. Photo Wikimedia Commons, in the public domain

The ship was doomed. Passengers continued trying to extinguish the flames; others threw themselves into the water. The two lifeboats on board were launched. Captain Sweet manned one and his first mate the other. They claimed they intended to ferry people back and forth from the burning ship to shore. The lifeboats together could accommodate slightly less than 50 passengers at a time. The fire spread so quickly that there would never be a second trip. Shrieks of terror sang to a backdrop of crackling fire and a softer chorus of unanswered prayers.

The passengers still aboard, and by then deserted by their captain, had to choose between the devil and the deep blue sea—remain on board and burn, or jump overboard to a certain death in the frigid waters. The Hazelton sisters, returning from school in the East, jumped. They clasped each other in a tight embrace and leapt to their deaths almost within sight of their home harbor. A young mother hugged her wailing infant close to her body and dropped from the burning deck into the restless waters that eagerly claimed them both. Family members kissed and hugged one last time before plunging to their death in the waiting waves.

Other ships hovered in the area and rushed to offer assistance to the blazing Phoenix. The Delaware, first to arrive, found only three survivors: three crewmen who clung tenuously to the rudder chains of the charred hull. Everyone else was dead. Lake Michigan was littered with bodies. The final death toll was estimated at 258, most of whom were Dutch immigrants.

The high casualty rate was attributed to the lack of sufficient lifeboats, but the cause of the fire would be blamed on the Second Engineer, who allowed the boilers to overheat. Why he did not properly monitor the boilers is the subject of much speculation. Perhaps he fell asleep. Perhaps he imbibed in a few too many drinks when they were delayed in Manitowoc that afternoon. Perhaps he had stepped away from his post for an unknown reason. Whatever caused him to shirk his duty, the ship was lost.

Click through to read excerpts from Royce's three books exploring Michigan's coasts:

Julie Albrecht Royce, the Michigan Editor for Wandering Educators recently published a three-book travel series exploring Michigan’s coastlines. Nearly two decades ago, she published two traditional travel books, but found they were quickly outdated. This most recent project focuses on providing travelers with interesting background for the places they plan to visit. Royce has published two novels: Ardent Spirit, historical fiction inspired by the true story of Odawa-French Fur Trader, Magdelaine La Framboise, and PILZ, a legal thriller which drew on her experiences as a First Assistant Attorney General for the State of Michigan. She has written magazine and newspaper articles, and had several short stories included in anthologies.

Let’s promote Michigan Travel. Books available on Amazon.