The approximate 6,000 ships that have succumbed to raging storms attest to the power of the Great Lakes. As I traveled, writing and compiling information for my three-volume travel series, Exploring Michigan’s Coasts, I heard or read the tales left behind by those ill-fated ships. They add a somber, but compelling backdrop to Michigan’s waterways.

The Plymouth, a schooner lumber barge with a seven-man crew, went down during the big storm of November 13, 1913. She was in the tow of the tug James A. Martin when the storm struck. More than a century later, questions remain. Did Captain Louis Stetunsky of the Martin desert the Plymouth? Did he seek shelter believing the Plymouth was stable? Did he intend to return when the storm abated?

The two vessels cleared the Menominee Light before they were forced to seek shelter. In an effort to keep the barge from crashing on the rocks, the tug towed it to nearby Gull Island, where it was anchored. What happened after that depends upon the story you accept. It is undisputed that the Martin left the Plymouth and headed for the shelter of Summer Island passage, where the Martin anchored to wait out the storm.

A few days later, Captain Stetunsky caused a sensation when he arrived in Menominee with his tug battered and bruised, looking much worse for the storm but miraculously afloat. Bystanders thought they saw ghosts. Everyone assumed the Martin and the Plymouth had gone down together in the maniacal gale.

Captain Stetunsky described the horror that he and his crew of eight suffered in the preceding days. The storm had started on Thursday and Stetunsky made no headway hauling the barge against the worsening weather. He attempted to anchor both ships in the lee of St. Martins Island. Unable to achieve the degree of security he thought necessary, he hauled the barge to a spot off Gull Island that he felt offered better anchorage.

Here the two versions of this account diverge. Stetunsky insisted that only when the barge appeared to be riding safely did he seek better refuge for his tug in the Summer Island passage. He was not leaving the Plymouth to whatever fate might befall her. The Martin lacked power to battle the storm and tow the barge. It was evident to him that both ships would founder if they remained tethered to one another. As it was, he had barely survived. He never mentioned why he did not take the crew of the Plymouth aboard his tug, but perhaps he did not consider one ship safer than the other.

Three days after the storm quelled, Captain Stetunsky returned to the spot he had left the Plymouth anchored. The barge had vanished. He sailed on to Menominee.

After several more days, parts of the lost ship began washing ashore—a hatch cover here, a piece of the cabin there. Broken lifeboats from the Plymouth were found in Ludington.

Skeptics argued that Captain Stetunsky abandoned the Plymouth and left her crew to perish. The evidence supporting this allegation arrived two weeks after the Plymouth vanished. A bottle was found five miles from Pentwater. Inside was a message, “Dear wife and Children. We were left up here in Lake Michigan by McKinnon, Captain James H. Martin, tug, at anchor. He went away and never said goodbye or anything to us. Lost one man yesterday. We have been out in storm forty hours. Goodbye dear ones, I might see you in Heaven. Pray for me. Chris K.” Chris Keenan’s body was found several days later on a beach near Manistee.

While the note has some facts wrong (Captain McKinnon instead of Stetunsky), the authenticity of the message has never been questioned, and under any interpretation, it seems clear the author of that note felt abandoned, whether in fact he was or was not.

The Plymouth when she was a steamer

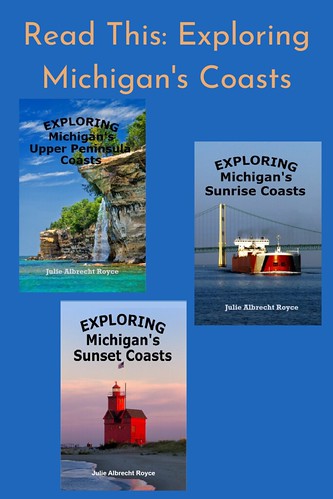

Click through to read excerpts from Royce's three books exploring Michigan's coasts:

Julie Albrecht Royce, the Michigan Editor for Wandering Educators recently published a three-book travel series exploring Michigan’s coastlines. Nearly two decades ago, she published two traditional travel books, but found they were quickly outdated. This most recent project focuses on providing travelers with interesting background for the places they plan to visit. Royce has published two novels: Ardent Spirit, historical fiction inspired by the true story of Odawa-French Fur Trader, Magdelaine La Framboise, and PILZ, a legal thriller which drew on her experiences as a First Assistant Attorney General for the State of Michigan. She has written magazine and newspaper articles, and had several short stories included in anthologies. All books available on Amazon.

Help promote Michigan. Books available on Amazon.

All photos in the public domain, via Wikimedia Commons