If you're going to Kathmandu, plan to buy pashminas. Here's what you need to know.

Readers who have waded all the way through one of my previous articles to the colophon at the end are perhaps aware that I am the manager of Sunrise Pashmina. So yes, this article is a shameless plug. On the other hand, there are quite a few top-quality pashmina producers in Kathmandu, and prices are generally cheaper than those you'll see on the Sunrise Web site. Tsering Choekyap, our Kathmandu producer, does not have run a shop or even a showroom; you could purchase from him directly anyway [info [at] sunrise-pashmina.com], but his wholesale prices are not vastly different from Kathmandu street prices. My recommendation: have fun exploring the dozens of pashmina shops in Thamel... especially right now, with the dollar trading at around 85 rupees, up 25% from June.

Of course, it is possible to get burnt in Kathmandu. If you pay premium prices for sucker schlock, the loss may be non-negligible, and if your giftee is more of a connoisseur than you, she may add insult to financial injury. Pashmina shopping is definitely not a case of "you get what you pay for." If you appear to be totally ignorant, the shopkeeper may or may not be eager to bring you up to speed. The more you know, or appear to know, the more likely you'll be offered a good deal on the best product.

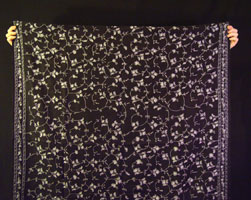

70% pashmina/30% silk shawls with print

So, what's a pashmina?

Or, more properly, since the fabric precedes the garment: What's pashmina? The short answer is that pashmina is cashmere -- the fiber or fabric made from the undercoat of certain breeds of domestic goats. These days the word pashmina can refer to the pure cashmere fabric, or to a silk and cashmere blend, or to a particular style of shawl (generally with twisted and knotted fringes).

The longer answer is somewhat more complicated. Most dictionaries will tell you that pashmina derives from the Persian pashm, meaning "wool," but the word has been used rather loosely for hundreds of years, and arguably could refer to any conventional woven fabric, whether made of sheep's wool, goat hair, shahtoosh (the endangered chiru antelope), cotton, rayon or even viscose. Nowadays, most so-called pashmina shawls are labeled as blends of cashmere (or pashmina) and silk, usually 70% pashmina/30% silk. Labels notwithstanding, a high percentage of shawls designated as pashmina or pashmina/silk are adulterated with sheep wool.

When Nepali pashmina shawls became the focus of an international fashion fad in the 1990s, the hype was that pashmina was different from and better than cashmere. Not true. According to Karl Spilhaus of the Cashmere and Camel Hair Manufacturing Institute, The word pashmina itself is not a legally recognizable term for describing fiber content in European or American law. The legal term recognized by the US Federal Trade Commission is "cashmere."

Cashmere is a fabric woven from the undercoat of certain breeds of goat. The scientific name for domestic goats in general is Capra hircus, and those bred primarily for wool, rather than meat or milk, are subcategorized as Capra hircus laniger. (Laniger is Latin for wool-bearing.) Not all lanigers produce cashmere. For instance, the angora goat (named for the region around Ankara, Turkey) produces mohair, a much heavier fiber, 24-40microns as opposed to 13-23 for cashmere, and a lot more of it: about 4-5 kg per year, as opposed to the 250 grams typical of a cashmere goat. There are quite a few cashmere breeds, found everywhere from the United States to Australia, but the epicenter of production for many years was Kashmir, the disputed territory between India and Pakistan. The French called the region and the goat-hair fabric Cashmere, and it became quite popular when Napoleon’s wife Josephine developed a yen for it. Pashmina is what Indians and Nepalis call cashmere, and this is actually a better word for the fabric since it at least has its roots in the native lexicon, whereas cashmere is a name imposed by European colonialists — sort of like calling the potato a peru or an inca.

In part due to the ongoing war in Kashmir, in part to the same factors that have made many Chinese products competitive, nearly all pashmina now comes from the high plateaus of Central Asia, particularly China's "autonomous republic" of Inner Mongolia. Nepal itself has the capacity to produce scarcely 30% of the goat hair used in its pashmina industry, but without dehairing and spinning factories Nepal's pashmina industry is totally dependent on Chinese yarn.

Another source of confusion Nepal's new trademark. A few years ago, Kashmir won legal rights to the trademark "Pashmina"; Nepal was forced to settle for "Chyangra Pashmina," which means "Goat Cashmere." There's no inherent difference, and there is no effective testing program to enforce standards, anyway.

Thanks to all the international attention, the word pashmina became associated with the configuration of the South Asian shawl. These were generally very large, with knotted fringes on the warp ends. (Warp refers to the lengthwise thread, held in place under tension while the shuttle moves back and forth width-wise, laying down the weft.) Anything in that shape, whether loomed from goat wool, cotton, viscose or acrylic, could be called a pashmina. The “genuine” article was supposed to be either 100% cashmere or a blend of silk and cashmere. The most popular fabric is 70% cashmere (which is used for the weft yarn) and 30% silk (used for the warp). This blend has several advantages. Because the silk is much stronger than goat hair, it can tolerate a lot more tension, and the fabric can be much tighter. When goat yarn is used for the warp, the tension must be reduced, and you get an open weave, rather gauzy and fragile looking. Cashmere, unlike silk, is very kinky at the microscopic level; the kinks trap air and give the fabric exceptionally good insulating quality. Silk is heavier, and gives the blended shawls a more elegant drape as well as a bit of a sheen. Unlike the 100% pashmina fabric, the pashmina-silk blends are amenable to a range of customizations, including jacquard, beading, and embroidery.

70% pashmina/30% silk shawl with print

70% pashmina/30% silk shawl with Jacquard weave

Beware of "100% Water Pashmina"! These shimmery reversible shawls may be 100% "water pashmina," but water pashmina itself is a blend of synthetic and/or other fibers.

What's the big deal about pashmina shawls?

Cashmere itself is a remarkable fabric. It is both preternaturally soft (and gets softer with age) and also exceptionally light. Because of its extraordinarily effective thermal insulation, pashmina shawls can be gossamer thin. The fullsize 100% pashmina shawl (190cm by 100cm, 80" x 36") is often referred to as a ring shawl because, despite its imposing dimensions, it can easily slide through a women's ring. The whole thing can be folded up into a little purse and tucked away in a pocketbook.

Shawls are versatile. Unlike a sweater, which is either worn properly or else in an unintendedly schlubby fashion, a shawl can be worn as a narrow scarf, tied beltike around the waist, draped over the entire torso, or wrapped like a skirt. It can serve as an airline blanket -- which is something our readers should take seriously, considering that studies have shown that standard issue airline blankets are frequently loaded with pathogens and allergens. They can be worn to the supermarket without looking pretentious, and they regularly appear at red-carpet events. Our Web site has special page on "How to Wear a Pashmina" with videos and text illustrating several dozen styles.

Pashmina, or cashmere, is itself a very special fabric. If it is stored properly, it can last a lifetime. Despite the "dryclean only" labels, cashmere can and and should be handcleaned. The process is simple; for full details on How to wash Pashmina, see the Sunrise Pashmina website.

70% pashmina/30% silk shawl with Jacquard weave

How to choose a pashmina

The shops and stalls of Asan Tole and Chetrepati are full of all kinds of "pashmina shawls": brightly hued acrylics, flat cottons, heavy wools, adulterated cashmere, and some genuine pashmina. Most of these wraps are extremely cheap, and not unattractive. Of course, the same could be said for the stuff they sell on the streets of New York.

Shawls and blankets for sale on Asan Tole

How can one recognize good quality pashmina?

The short (but virtually useless) answer is that you can feel the difference. Pashmina, even blended with silk, is soft, spongy, almost buttery, and it gets softer as it is used.

But... lots of fabrics are soft, and if you aren't already familiar with cashmere, it's hard to be sure what might be meant by "soft, spongy, almost buttery." In fact, freshly woven pashmina is not soft enough for current market expectations: these days, virtually everybody uses a chemical softener, which is mixed into the dye. That apparently does not harm the fabric, but it does make the short answer somewhat useless.

Given the money at stake, and Chinese ingenuity, it is not surprising that counterfeiters have made considerable progress in recent years. Merino sheep wool can be descaled to make it look like goat yarn. An objective determination requires a qualified technician, but there are very few textile fiber labs in the world, and they don't cater to curious shoppers.

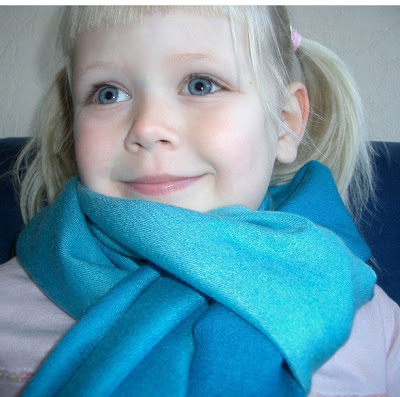

100% pashmina shawl (above and below). Note the relatively open weave, as compared with tighter weave of pashmina-silk blends as seen in the shot of the turquoise muffler just below the close-up of the beige shawl.

Tight-woven 70% pashmina/30% silk muffler

A few general pointers:

Good pashmina yarn has a preponderance of long fibers. Any wool or cashmere fabric may pill up (form little balls) if it is rubbed, as occurs when it is worn under a belt or a coat. If there are a lot of short fibers, the pilling will be more noticeable. Pilling should stop after the first wash.

De-hairing is the most time-consuming aspect of pashmina production. The presence of thick guard hairs and extraneous matter such as straw fibers is a bad sign.

Many first-time pashmina buyers are attracted by the fuzzy look and feel of brushed wraps. Brushing, however, weakens the cloth, induces shedding, and turns your wrap into a dust mop for lint. True connoisseurs eschew both full-brushed and semi-brushed pashminas. If you really want one, just lend your shawl to your cat for an afternoon.

Distinct grades of 100% pashmina yarn: 5kg spool of Grade A is lighter and bulkier than Grade B

What about that smell?

Goats are smelly creatures, and their oil (lanolin) has a distinctive odor. The smell might be considered a good thing, as the lanolin protects the yarn. On the other hand, it dissipates with use and laundering. So it might be considered a badge of authenticity, not necessarily prized by others in the elevator.

What if it smells like airplane fuel? We've had that problem, actually. Embroidery entails the tracing of a design on the shawl with a soap pen; the marks are removed with a petroleum based solvent. The shawl then has to air out to allow the smell to go away. Unfortunately, the guys who do this work live with that smell all day long and, as we all know, the nose becomes desensitized to even the most foul odors within about fifteen minutes. So those guys don't necessarily know when the smell is gone. If the shawl is folded up and packaged too quickly, it may have an odor when you get it. The odor goes away if you air the shawl on a clothes line... or wash it.

Loading the yarn onto bobbins

Pashmina weaver at loom (above and below)

Massaging the new shawls to relieve the stress on the warp yarn and allow the fibers to relax back into their natural shape.

Handmixing the dyes

Proper temperature and agitation are critical factor in dying

Drying pashminas after dying

Twisting and knotting the iconic fringes

Tracing the pattern for embroidery

Handstitching the embroidery

Ironing the finished shawls

What about price?

It's not actually true that you get what you pay for. The fancy designer brands are generally purchased in quantities that cannot be supplied by local craftspeople. Instead, the shawls are mass-produced on machine looms. They may look better made than handloomed shawls (more regular, straighter edges, fewer "defects"), but... which would you prefer: a Bokhara Persian carpet machine-woven in Shanghai or one woven at home in a family-owned workshop over a period of months and months by a traditional craftsperson? Same thing goes for pashmina.

An increasingly important factor is the yarn itself. Four or five grades of pashmina wool are now available in Kathmandu, and the difference between the top grade and the next best can account for a 25-35% difference in cost. The variation in pashmina wools has to do with the length, fineness, strength, and softness of the fibers; inferior grades are impure and/or poorly sorted, including an unacceptable proportion of rough guard hairs (as distinct from the downy undercoat), overly short fibers, and other impurities. A relatively minor cost factor is the dye. Many pashminas are colored with dyes produced in India; these chemicals are cheaper and less permanent than the Swiss dyes that we use.

Two-ply? Four-ply?

To begin with, the term ply refers to a distinct thread that may or may not be twisted together with one or more similar threads to form a thicker thread. Single-ply is a fabric made with elemental threads ; double-ply or two-ply fabrics are made with double-twisted threads (at least in the weft, but presumably sometimes also in the warp).

To be clear, very very few (and perhaps none) of the current shawl producers in Kathmandu are using true double-ply yarn. In fact, multiple-ply yarn is now used almost exclusively for knitted goods. These days shawl producers in Nepal use using an adjustment of paddles in the loom to control fabric density rather than actual double-ply yarn. The shawls marketed as double-ply are actually four-paddled shawls -- as opposed to two-paddled. Most 70/30 and 50/50 shawls and mufflers are four-paddled, while 100% pashmina shawls are two-paddled.

Remember: in pashmina shawls, more is not better. If it were, women would be wearing bed-spreads or horse-blankets, rather than shawls. The modern pashmina shawl has evolved to meet the need for a warm AND light wrap. The paddle-adjusted shawl may be a shade less dense than a double-ply, but it has undoubtedly achieved its international success due to the fact that it so successfully achieves the desired balance of warmth and weight.

Where to shop

In many cases, travelers are advised to shop where the locals shop. In fact, pashmina shawls are not a staple among Nepalese women. They do wear shawls, but cashmere is way too expensive for ordinary folk. So does that mean they are inauthentic? Yes and no. Globalization of arts and crafts is an old story in Asia. The Chinese pagoda roof was developed in Kathmandu Valley by Newari architects. Most Persian crafts were imported along with Indian and Armenian artisans. The mirrored embroidery common all along the old Overland Route from Istanbul to Kabul to Peshawar and Agra was probably developed by Gujaratis (a.k.a. gypsies or Roma). The so-called Tibetan carpets marketed in Nepal were invented by Swiss traveler-photographer Toni Hagen. He invented a new "bed size" carpet, woven on a Tibetan-style loom, to create a cottage industry for Tibetan refugees in Nepal. Actually, Tibetans did use long carpets for sitting on during the day and sleeping on at night, but they were much narrower, designed to cover the wrap-around benches that went all around the "big room." The point is, Nepalis (like Kashmiris, Indians and Tibetans) have been traders for centuries, and there is an authentic tradition of adopting foreign crafts (such as the Persian pashm) for export and for sale to visiting tourists.

That being said, the place to look for the best pashmina shawls is logically in the areas most frequented by upscale tourists: around the Yak and Yeti, theAnnapurna, the Soaltee and other ritzy hotels; and of course in Thamel, and onNew Road near Durbar Square.

My favorite strategy is to start out by implying that I'm looking for inexpensive items, then ask what would be the next step up, pricewise -- and ask for an explanation of the difference in quality. Then ask for the next step up, and so on. In Nepal, you're expected to negotiate on price -- even if the price is marked and advertised as "fixed." To negotiate effectively, you need to actually leave the store, and come back another day. To prepare for that, you should start out be saying you're just checking prices and not ready to buy; ask for the salesperson's card and write down final offers. Keep hope alive, don't let the negotiation get grim, but don't let it seem a game either. As someone (perhaps La Rochefoucauld) once said, "The boys throw stones in jest, but the frogs die in earnest." Pashmina in Nepal is a very high stakes game.

Full-surface embroidery on 70% pashmina/30% silk shawl

Seth Sicroff is the Nepal Editor for Wandering Educators

Manager,

All photos courtesy and copyright Seth Sicroff