What is it like to be a writer? Canadian author Marianne Brandis on the creative life

As a writer, I am entranced by words. I love them – writing them, reading them, re-reading them, finding writers that use them in creative, interesting ways. To say that my life is one of writing and reading is not an overstatement, but rather, a joyful way to be in the world.

When I discover writers that I love, I dig in deeply to their words. They enrich my life, thoughts, reading. And, when I have the ability to share the talents of such writers? Well, this is one of the reasons I started this website.

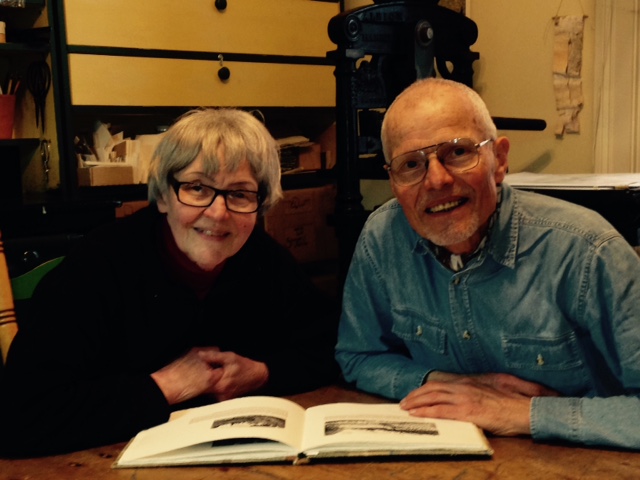

One such writer I found in a circuitous and fortuitous manner – Canadian author Marianne Brandis. While we were in Stratford, Ontario this past fall, we were lucky enough to visit with her brother, the artist Gerard Brender à Brandis. We featured him as an artist of the month, and I was intrigued by his tales of working with his sister, walking every day, writing books together. I’ve been in conversations with Marianne since this fall, and will be honest: her writing is extraordinary. She has written historical novels, stories of place, creative non-fiction, and much more. Her reflections on the artist's workplace is a beautiful and a unique glimpse into the writing life.

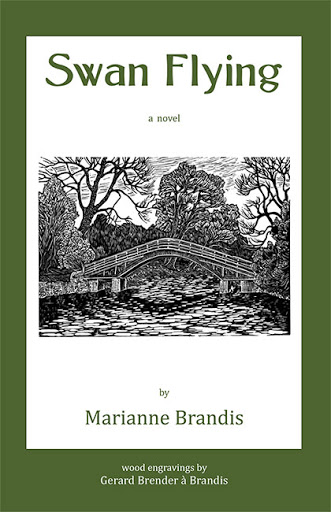

Illustration from Swan Flying

And so, when I learned that Marianne (with engravings by Gerard) has a new book coming out this May, Swan Flying, I wanted to ask her more about her writing. She’s a grande dame of writing (albeit a quiet one), and, at 77, has much to teach us about writing across a lifetime. I encourage you to delve deeply into her writing – both here, in this lovely interview, and on her site and in her books. Her writing is beautiful, thoughtful, interesting, and meaningful. Take a look...

Photo:Marti Maraden

How did you get started writing?

Since my teens, writing has been one of my main ways of “being.” The act of writing was an enjoyable creative activity, and the world that I created by writing was a good (though not always comfortable) place. I wrote a journal (am still writing it), and although the earlier volumes are lamentably full of adolescent silliness there are also the ruminations of a writer, seeing and reflecting on possible stories, articulating feelings and ideas and, above all, asserting repeatedly that I intended to be a writer. Besides that journal, I wrote stories, plays, and poems, and I began feeling my way into the bigger and more complicated demands of the novel.

All that early writing was apprenticeship. Besides writing, I read. A creative writing course that I took in my second year at university set me on a lifelong program of reading other people’s work as a way of learning what I needed to know for my own writing: what to look for in the published work I read, what questions to ask of it. Frequently, as soon as I had finished reading a novel as an “ordinary” reader would read it, I went back to the beginning and read it again, making notes, marking up the book (always lightly and in pencil because I hate heavy-handed markings), observing and analyzing and learning.

The first of my novels to be published, This Spring’s Sowing, appeared when I was 31. It was the only one to be published of a group of four that I had written in my twenties. As regards the other three – well, failing is an essential part of learning. I analyzed why they failed.

After This Spring’s Sowing, I began to write historical fiction, and I wrote half a dozen of such books, of which five were published. They won awards and, though never aimed exclusively at early-teens readers, were used in quite a few schools to help teach history.

Historical fiction is, more obviously than many other genres, a blend of fact and fiction, and at a certain point I veered towards the “fact” side, into creative non-fiction, including life-writing. Drawing on extensive family archives, I wrote a biography of my mother, Frontiers and Sanctuaries: A Woman’s Life in Holland and Canada, which, like her own writings, contains a many-sided view of immigration. I wrote the first professional biography of my brother Gerard, who is a well-known wood-engraver and creator of limited-edition handmade books, and prepared a bibliography of his handmade books and of the trade publications in which his wood engravings appear.

What inspires your writing?

I have a strong drive to write, and I’m never short of ideas. I write every day – on one of the current projects, or adding to the material for any of several ongoing memoir-type works that are still in the note-making and first-draft stage. Writing (the whole big thing, with all the related aspects) is part of almost every waking moment (and no doubt many of the sleeping ones as well); it’s like a river that runs through my life, constantly flowing. A jug-full of the water gets dipped out from time to time and held up for other people to see and read but the river flows lavishly on. This means that each work is not just a self-contained entity but part of the whole stream, connected with the others by similar themes or situations, by episodes revisited, or by my personal experiences.

I ruminate quite a lot about the creative life, the element in which I’m immersed. What is it like to be a writer?

Well, for one thing, writing is solitary; there may be writers who work in groups but I’m not one of them. And it’s nearly invisible until there’s a finished book to show for all the work. (By the time people are reading one work of mine, I’m already immersed in the next one.) Unlike visual artists, writers rarely if ever open their work-places to the public because there’s nothing interesting to see: a computer, filing cabinets, books, a litter of papers. All the same, that small physical space is the context for the huge mental and imaginative world which is “open to the public” when people read the books.

Ideas are vital and precious – every kind of idea, whether it’s a vivid phrase, or an insight into human behaviour, or an observation about the outside world, or an idea for a whole book. Once the idea is written down, I work with it. (What implications and associations does it have? Where does it lead me?) Exploring, developing, and using it may involve linking it to an already-existing cluster of ideas.

Because all my writing has a historical dimension, research is a part of that development. Even a book set in modern times needs research – finding details about place and weather, checking an allusion to make sure that I have it right, researching a profession or occupation with which I don’t have much experience. Research – in books and elsewhere – is a large part of my life, and I’ve researched many dozens of topics.

Research links with imagination. I wrote about this in connection with the book The Grand River / Dundalk to Lake Erie, on which my brother Gerard and I (see below) collaborated. Gerard and I were asked to write blogs to be posted on the publisher’s website, and here are my reflections on how research and imagination work together.

I always start writing early in the development of a book-sized idea: starting to write is my way of exploring it and seeing where it leads. I love revising, which is for me an essential part of the creative process, and that means not just refining the form and writing style but also delving into the rough shape of the story, digging for its potential, adding dimensions. Each layer of revision leads to more.

Writing a book usually takes years. Projects overlap; when a manuscript is first submitted to a publisher, before I get it back for (perhaps) further revision, I begin work on the next, or pick up an earlier one that is still in progress, knowing that that may again be interrupted. This makes it hard to answer the common question “How long did it take you to write this book?” The whole span covered could be anywhere from two to fifteen years, the actual writing time for that particular work as much as four or five. This complicated process – because each book is complex in itself, a whole big mental space – is made manageable by my long-time habit of writing an “interruption note” every time I have to put one project aside temporarily to work on another. The interruption note tells me precisely where I was when I had to break off.

During the span of time required to complete each book, the drive and enthusiasm for the project have to be maintained. For me, that’s not difficult, partly because of the stream that links all the books. If the drive and enthusiasm fail for that book fail, then it's not a viable project and had better be abandoned.

Once the book is published, I’m much involved in promotion. That’s not very creative work, but is part of the writing career.

My creative life is rooted in place, in my house, all of which is “writing space”; most of the actual writing happens in only two rooms, but I do research reading in the living room in the evenings. There are books and papers everywhere. My work is not portable: I couldn’t take my laptop and sit at a park bench or in a coffee shop and work. I need the papers and the files – and the space that is imbued with past creativity.

This work space, as I said earlier, is not interesting to an outsider, but some aspects of the whole career are done in other places. Here are a few glimpses of me at work.

I’m running a memoir-writing group.

I’m doing what all writers have to do – promoting books. This is my table at a book fair in a church hall. Book displays like this give people an idea of the range of my work.

For the writing of my book Thinking Big, Building Small: Low-tech solutions for food, water, and energy, which is about the work of my brother Jock – a social entrepreneur and inventor of low-tech food-production and -processing devices to help farmers in the developing world – I went with him to Malawi to observe him at work as he developed a water pump. Here I am with him, making notes.

This looks blissfully relaxing and idyllic, and it was, but actually I’m working on The Grand River. I’m sitting near the river observing and thinking and making the kinds of notes that enabled me to write 50 short essays of information and reflection about that river and about “riverness”, the private life of the Grand River in southern Ontario and other rivers on the planet.

How do you settle on a topic for a book (you have so many!) - in your words, the roots of a book?

My books have some of their origins in the constant stream that I described earlier – often I don’t know precisely where, but I do know that each book springs from a number of different origins. The initial idea is not necessarily a personal experience: it’s almost always that of a character confronting a situation, and such ideas can come from anywhere. As I develop that idea and start writing, some personal experiences help to flesh out the original story, getting woven in as I construct the first draft and then go through the many, many revisions.

Writing about pioneering life in my historical novels proved to be a natural for me because when we first emigrated from the Netherlands to northern British Columbia in 1947 we lived on what was in effect a pioneer farm. So I had hands-on experience with a wide range of domestic and farm chores done in a very simple pioneering kind of way – and, like all of us in the family, I thought like a pioneer.

Ideas also come from other books, and from the research I do. I came across the core idea for Elizabeth, Duchess of Somerset, in a biography of Jonathan Swift which I was reading for a never-published book about the Queen Anne period. (Elizabeth, to my pleasure, was published.)

Some types of ideas or stories especially interest me. I always like to look at the underside of history – the back of the tapestry – the lives of ordinary people, and the daily lives of prominent people. Elizabeth is, among other things, about the working life of a duchess – the working life, managing her household and, in her mature years, working in the household of Queen Anne as lady in waiting and then Mistress of the Robes. I learned about that subject from (among other sources) her household records, which I used in England.

For the text for The Grand River, I researched and brought together elements that are often considered in isolation – many environmental and historical issues, the dialogue of water and land and humans, the way in which a watershed is like a hand holding the ecosystem (including humans) in its palm.

One important area of my writing life is the collaboration with my brother Gerard Brender à Brandis, who was the subject of a previous interview on this website. We do most of our work separately, but we’ve created more than a dozen books together, including some of Gerard’s handmade books as well as trade publications. His wood engravings appear in most of my historical fiction – he greatly enjoys depicting historic houses and household/farm objects – and we’ve created several chapbooks. The Grand River / Dundalk to Lake Erie is a recent joint project, and the latest one is Under This Roof. While creating these books – from the very beginning and throughout the process of producing the work – we discuss the integration of images with text, and other artistic aspects of the book. My biography of Gerard, “Artist at Work: Gerard Brender à Brandis”, gives more information about a number of these projects.

photo: Doug Wilson

Your new book, Swan Flying, is out now - what influences in your life formed this book?

Swan Flying, my 14th book-length work, does indeed have some roots in my own life. (Probably all fiction has roots in the life of the author, no matter how much altered.) It draws on my experiences of immigration, of retirement, of bereavement, of the need to tidy up after the death of a loved family member – and of creativity as a way of making sense of all these experiences. The setting – Stratford, Ontario – is where I live now. But the book is not autobiography in any direct sense. It’s a fictional exploration of being on a complex and difficult threshold in one’s life and of finding – recognizing – the resources to move into the next phase.

Marta de Witt, the central character, is a just-retired history professor who is summoned to Stratford to be with her dying Aunt Hilda de Witt. Dealing with both retirement and imminent bereavement raises big questions about how and where she’s going to live for the rest of her life, who she’s going to be. During the twelve days covered by the novel, Marta stays in her aunt’s house, which for seventy years has been the home of de Witt family. By listening to what the house tells her, by reconnecting to her family, and by paying attention to the welling up of creativity inside herself, she’s able to begin moving across that threshold.

These issues – retirement, bereavement, the need to find the resources to rebuild one’s life – are common human experiences. Yes, I was drawing on my own life but I fictionalized those experiences to give them universal dimensions.

When I conceived and planned the book, and while I wrote the first draft, it was not the large abstractions that were in my mind. As always in my novels, I began with a character confronted with a difficult situation. The character and the situation have to be carefully designed to work together: if the problem is too easily solved there will be no story, whereas if it’s too big it will overwhelm the character. Actually, the situation is a series of problems: solving one leads (as it usually does in real life) to another. The character also changes as a result of the interaction with the situation. This is how a plot is developed to fill a book.

This basic structure is clothed in detail. All of my books are rooted in reality – a specific (real) place, a daily routine, an actual calendar, a season and its weather. This is how our lives feel, and readers of Swan Flying will find themselves stepping into Marta’s life – making to-do lists, watering plants, having a drink with a neighbour – and at the same time reflecting on the big issues, living with them, shaping a new life for herself at the age of sixty-four.

What's up next for you?

A large factor in where I am now in my career, and in my sense of identity as a writer, is my age. I’m 77, and while at this moment I’m still functioning well I don’t know for how long that will continue.

But I’m hopeful, and I have several projects lined up. The next major one will probably be a translation and editing of a diary that my mother wrote during the Second World War in the Netherlands. She was a gifted writer, and her diary is a vivid and detailed account of the life of a young mother in a very dangerous situation. I drew on it for two of my past books – Special Nests and Frontiers and Sanctuaries: A Woman’s Life in Holland and Canada. I’ve translated all of the diary (I had to interrupt that project to work on another one) but the translation needs fine-tuning and I have to write an introduction and conclusion, and explanatory notes.

Another, and ongoing, project is a memoir for which I’ve already written a lot of material and to which I keep adding. Selection and shaping are needed to produce something readable.

The life of an elderly writer is full of challenges – memory gaps, lower levels of energy, etc. – but also of rewards. In my case, there is a long career to look back on. One of the rewards is the awareness that I still have the ability to write and still have a career, and that my experience allows me to do things more efficiently than I once did. At the same time I’m constantly moving into new territory, exploring new things, learning new techniques. The stream is still flowing.

Part of the “looking back” that I’m doing is the result of my need to downsize, so I’m in the process of sending writing papers to the McMaster University Archives. It’s hard to say good-bye to them: part of me wants to hold onto what I’ve created (especially if it was not published) because it’s an integral part of who I am, but another part knows that I have to move it on so that I can simplify my life in preparation to living smaller. Living smaller in terms of physical surroundings and belongings need not – or not yet – mean living less richly in my creative inner life and in my “home” atmosphere of books and art and music. Perpetuating my present life into an old age of that kind is, right now, one of the projects for which I’m drawing on my own creativity.

Learn more: http://www.mariannebrandis.ca/

All photos courtesy and copyright Marianne Brandis, except where noted

-

- Log in to post comments