40 years of Mexican Modern Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

What were the social, political and cultural elements that shaped the unique, colorful artworks created by such famed Mexican artists as Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, Jose Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros?

Diego Rivera, Portrait of Martín Luis Guzmán, 1915, oil on canvas, Fundación Televisa Collection and Archive. © 2017 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico D. F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

José Clemente Orozco, Barricade, 1931, oil on canvas, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, given anonymously. © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SOMAAP, Mexico City

This is what Paint the Revolution: Mexican Modernism, 1910-1950, a blockbuster exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, explores. The most comprehensive exhibition of Mexican Modern art in 70 years, the exhibition opened June 25 and closes Oct. 1, 2017.

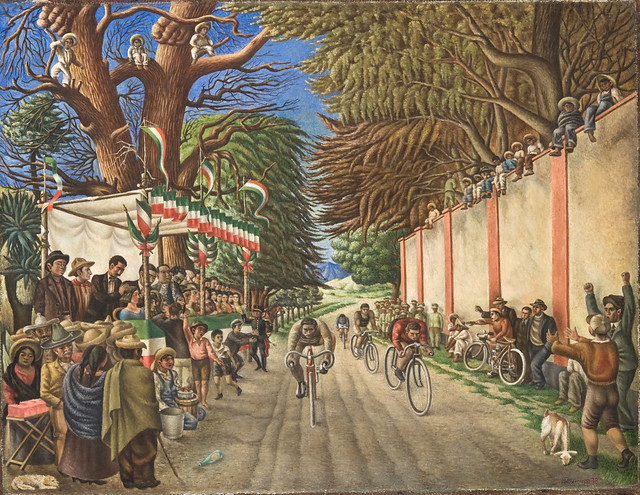

Antonio Ruiz, Bicycle Race, 1938, oil on canvas, Philadelphia Museum of Art, purchased with the Nebinger Fund.

In this, its final U.S. venue, art lovers see 175 artworks that run the entire art gamut. Artworks on display include everything from easel paintings, broadsheets, prints, photographs, books, and newspapers, to large-scale portable murals.

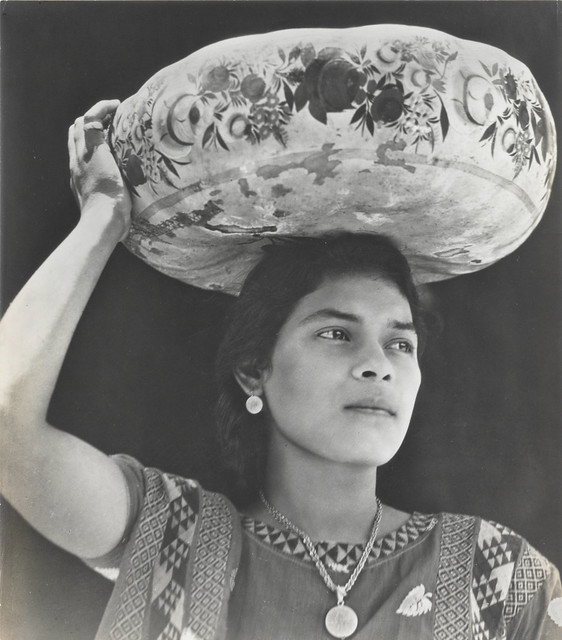

Tina Modotti, Woman of Tehuantepec, c. 1929, gelatin silver print, Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Carl Zigrosser.

While some artists are world famous and favorites of art aficionados, many of the artists and their works will be new to museum-goers. Contemporaries of the famous artists featured in this exhibition are: Manuel Alvarez Bravo, Carlos Merida, Roberto Montenegro, Miguel Covarrubias, Alfredo Ramos Martinez, and Gerardo Murillo.

Roberto Montenegro, Maya Women, 1926, oil on canvas, Museum of Modern Art, New York, gift of Nelson A. Rockefeller. © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SOMAAP, Mexico City

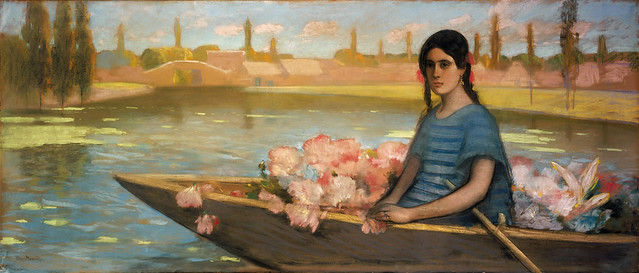

Alfredo Ramos Martínez, Flower Seller, c. 1916, pastel on paper on canvas, Pérez Simón Collection, Mexico City. © The Alfredo Ramos Martínez Research Project, LLC

“While some of the artists represented in Paint the Revolution will be familiar to visitors, many of the names and images will be new to Houston audiences,” said Gary Tinterow, MFAH director who expressed gratitude to colleagues at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City for organizing the exhibition.

The 20th century brought about profound changes worldwide, but the first social revolution began in Mexico in 1910. Mexican peasants, workers, and society in general had endured the dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz from 1877-80 and from 1884 to 1911.

While historians credit Diaz with modernizing Mexico’s transportation and banking system, they also acknowledge Diaz allowed foreigners to buy up most of Mexico’s land, converting its citizenry into foreigners in their own land. In fact, Mexicans could only own land if they had a formal legal title.

Diaz ruled with an iron fist for 35 years. In 1911, he was exiled to Paris, where he died shortly after. It was against this historical backdrop of war, abject poverty, and feelings of hopelessness among the abundant peasant farmer population that Mexico’s modern artists emerged.

María Izquierdo, Our Lady of Sorrows, 1943, oil on board, private collection.

“Scholars have long understood Diego Rivera, Jose Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros as the driving forces behind muralism and transformation that swept Mexican art after the Revolution,” said Mari Carmen Ramirez, MFAH Wortham Curator of Latin American Art.

David Alfaro Siqueiros, George Gershwin in a Concert Hall, 1936, oil on canvas, Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin. © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SOMAAP, Mexico City

This exhibition, which follows a chronological order and opens with a group of artworks created in the tumultuous decade following 1910, covers 40 years of Mexican Modern art produced in a wide variety of artistic forms. Each section notes years and decades that influenced a number of artists.

The goal is to provide visitors with an in-depth understanding of the factors that shaped the development of Mexican Modern art during the long period of social and political upheaval worldwide, but especially in Mexico.

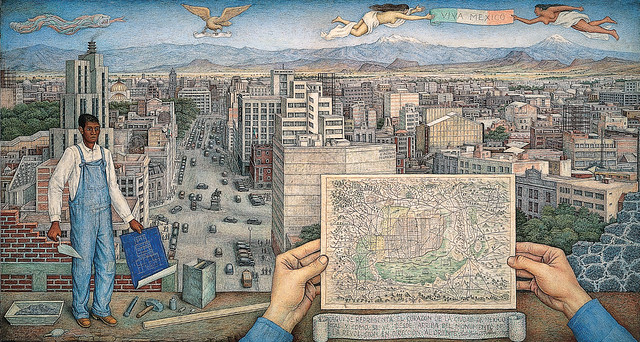

Juan O’Gorman, Mexico City, 1949, tempera on Masonite, Museo de Arte Moderno, INBA, Mexico City. © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SOMAAP, Mexico City

Beginning in 1910, Mexican artists focused increasingly on capturing the Mexican national identity. Despite acknowledging the emergence of international art movements such as Impressionism, Cubism, and Symbolism, artists chose to communicate their Mexicanidad or “Mexicanism,” using various media.

A good example of this Mexican aesthetic is The Offering, a 1913 painting by Saturnino Herran. The work illustrates the uniquely Mexican holiday known as Day of the Dead. The painting, filled with symbols of national identity and tradition, features a boat filled with marigolds on its way to market to observe the festivity.

Saturnino Herrán, The Offering, 1913, oil on canvas, Museo Nacional de Arte, INBA, Mexico City.

In 1920, as the Mexican Revolution raged on with more than a million Mexicans dead, President Alvaro Obregon ushered in a new government under the newly crafted Mexican Constitution of 1917.

Obregon felt public education and the arts could help unify a seriously divided country. He chose the monumental qualities of mural paintings as a tool to help unite Mexicans. Obregon’s commissioning of Rivera marked a turning point in Mexican Modern art.

Three historic murals created by Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros, often called “los tres grandes” or the “three great ones” in Spanish, are digitally reproduced and projected for visitors in the museum galleries.

Digitized mural representations are: Rivera’s Ballad of the Agrarian and Proletarian Revolution (1928-29) on view at the Secretariat of Education in Mexico City; Orozco’s Epic of American Civilization (1939-1940) on display at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, and Siqueiros’ Portrait of the Bourgeoise (1939-1940).

Painter Adolfo Best Maugard (1891-1964) led the effort in Mexico to democratize culture. He established a system of drawing used in primary schools across Mexico. The Powdered Woman, (1922) oil on cardboard, is one of those featured in the exhibition. Works by artists such as Abraham Angel, (1905-1924), Julio Castellanos (1905-1947), and Rufino Tamayo (1898-1991) were all influenced by Maugard.

Adolfo Best Maugard, The Powdered Woman, 1922, oil on cardboard, collection of Lance Aaron and Family.

In the 1920s, two groups of artists emerged. These artists began rejecting history and traditions in favor of international, cosmopolitan and urban trends in painting. Contemporarios and Estridentistas, the two groups focused on cities, factories, trains and everyday modern life in Mexico.

Meanwhile, in the United States during the 1920s and 1930s, there was a demand for Mexican art. Consequently, Diego Rivera, considered the greatest Mexican painter of the 20th century, Frida Kahlo, and Jose Clemente Orozco, two of Mexico’s greatest artists, traveled to the U.S. to fulfill an emerging desire for modern Mexican art.

Diego Rivera, Dance in Tehuantepec, 1928, oil on canvas, collection of Eduardo F. Costantini, Buenos Aires. © 2017 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico D. F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

This section of the Paint the Revolution exhibition examines the artworks generated by the arrival of these Mexican artists. Their individual works of art, which include thought-provoking imagery-convey the complex history between Hispanic and Anglo relations on the North American continent.

Highlights include Kahlo’s Self-Portrait on the Border Line Between Mexico and the United States (1932), and Alfredo Ramos Martinez’s Pottery Vendors (1914) illustrating Mexican women drawn directly onto a Los Angeles Times beauty column.

Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait on the Border Line between Mexico and the United States, 1932, oil on metal, collection of María and Manuel Reyero, New York. © 2017 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico D. F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The exhibition culminates with a resurgence of politically and socially infused art from the mid-1930s to the 1950s due to national and international events that impacted Mexican culture. The Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) and World War II (1942-1945) brought a number of exiled European artists to Mexico.

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Calle Cuauhtemoctzin, Mexico City, 1934, printed 1946, gelatin silver print, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Ford Motor Company Collection, gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell. © Henri Cartier-Bresson/ Magnum Photos

This final section features David Alfaro Siqueiros’ War, a painting he did after returning from fighting in the Spanish Civil War against the Fascists in 1939. Other works in this final section include those of Wolfgang Paalen and Alice Rahon.

“We’re thrilled to offer visitors the opportunity to examine firsthand the emergence of Mexico as the center of Modern art,” Tinterow, who left his position at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art to join the MFAH as director in 2012.

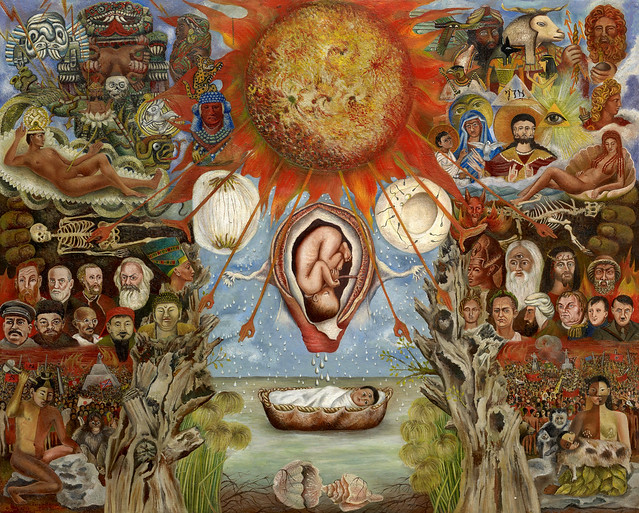

Frida Kahlo, Moses, 1945, oil on Masonite, private collection, Houston. © 2017 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico D. F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

For information on admission and museum hours, call (713) 639-7878 or visit www.mfah.org

Paint the Revolution: Mexican Modernism, 1910–1950

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

June 25–October 1, 2017

Upper Brown Pavilion, Law Building

Rosie Carbo is the Lifestyles Editor for Wandering Educators, and is a former newspaper reporter whose work has appeared in newspapers and magazines nationwide. Some of those publications include People magazine, The Dallas Morning News, The Houston Chronicle, and San Antonio Express-News. Some of her features were redistributed by The Associated Press early in her career as an award-winning Texas journalist.