The Four Corners region (southwestern corner of Colorado, southeastern corner of Utah, northeastern corner of Arizona, and the northwestern corner of New Mexico) offers many opportunities to explore Native American culture. Road trips with stops in the towns of Pagosa Springs and Durango, or at landmarks such as Chimney Rock National Monument or Mesa Verde National Park, can easily add a detour to the Southern Ute Museum in Ignacio, Colorado.

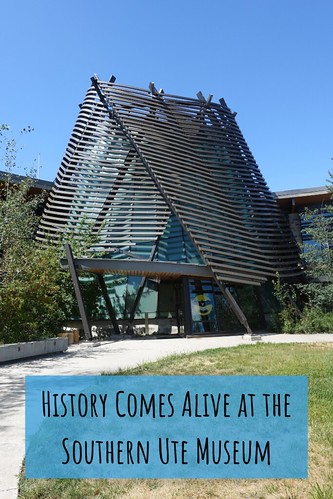

Seattle’s Jones & Jones Architects and Landscape Architects, Ltd., the same firm that designed the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., worked with the local Ute tribe to create a 54,000 square foot building landscaped with an assortment of indigenous plantings near the Los Pinos River. The building’s unusual round shape, with an abundance of natural light shining through the dramatic glass atrium, symbolizes the Ute’s belief in the Circle of Life. This architectural gem, constructed in 2011, houses more than 1,500 Native American artifacts. It’s a rare attraction in a remote town located about 25 miles southeast of Durango and 50 miles southwest of Pagosa Springs.

Colorado’s longest continuous residents, the Southern Ute Indian Tribe, lived for centuries in parts of Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, Eastern Nevada, Northern New Mexico, and Arizona. Social scientists have found evidence that suggests that the Ute migrated to the region around 500-800 years ago. Today, the ancestors of the Mouache and Caputa bands of the Southern Ute Tribe are based in Ignacio. The Southern Ute Tribe created the museum to preserve and promote their history and culture. A poignant sign inside the museum reminds today’s youth to embrace the past:

“Young people need to see all these things. They need to know who they are and where they came from. If you teach them, they won’t forget.”

Upon entering the museum, we were greeted by a Lummi Nation Bear Totem Pole. This totem pole is on loan to the museum form the Bear Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition. Museum visitors are encouraged to touch the carving to derive good fortune.

Numi Nuuchiyu, We Are the Ute People, is a permanent exhibit that takes visitors on a self-guided tour of Ute history from prehistory to modern times. Near the entrance, a sign informs visitors that while the Utes speak in many voices, they are all related. The curators effectively utilized life-sized replicas, audiovisual equipment, and interactive multi-sensory exhibits to tell the Ute’s story. Despite all of the obstacles that were placed in this tribe’s path, their message is clear. “We are still here.”

While the permanent exhibit is organized into six distinct themes—Welcome, Long-Time Ago, Camp Scene, Reservation Life, Celebrating Traditions, and Current Events—most visitors will walk away with a comprehensive overview of the history and culture of this indigenous group.

The first displays depict hunting and gathering culture relying on native plants and indigenous animals—deer, buffalo, rabbits, elk, marmot, skunk beaver, and birds—to survive. They developed food preparation methods focusing on drying, parching, grinding, pounding, preserving, and cooking. Interestingly, the Ute people did not hunt their protector, the bear.

Women were responsible for stitching together approximately 12 elk hides for the tipi covers, in addition to the care and maintenance associated with assembling and disassembling the structure along with the everyday caretaking roles of their families. Ute women have always been the “ backbone of the family.”

The adverse effects of a series of government treaties are well documented in exhibits pointing out many of the more delicate details left out of most American history books. After being hunters and gatherers for generations, the Utes were suddenly forced to become farmers and ranchers. Their leadership was divided. Some opted to follow War Chief Buckskin Charlie (ca.1840-1936) and lived as farmers on assigned plots of land. The chief’s efforts to avoid conflict were rewarded when he received the Rutherford Hayes Peace Medal in 1890. Along with Geronimo, Buckskin Charlie rode in President Theodore Roosevelt’s inaugural parade in 1905.

Other tribe members elected to follow Ignacio (1828-1913) and resisted the government’s demands. Ignacio thought it unwise to send children to reservation schools or accept land allotments. Instead, he chose to reside on reservation land that was held in common. Most Ute children attended schools with an assimilating agenda that attempted to strip the Utes of their culture. With the inability to live according to their former ways, a sizable number of Utes became dependent on food rations that the government offered in exchange for Ute land. The Indian Organization Act of 1934 attempted to alter the federal government’s attempts to forcibly assimilate the Native Americans into American culture.

While most visitors will probably spend a little more than an hour walking through the permanent exhibit, one could easily take additional time reading through the biography templates, the display signs, and examining the timelines that pinpoint historical events that affected the Ute Tribe’s wellbeing up until modern times.

Examples of the Ute’s handicrafts, clothing, and language are found throughout the museum. With less than 100 fluent Ute speakers alive today, linguists and tribal leaders have an upward battle to preserve a language that is on the verge of extinction.

Since World War I, the Southern Ute Indians have supported America’s military. In the Northeast Hall Alcove, a Southern Ute Veterans exhibit is a living reminder to the Ute’s dedication, service, and sacrifice to the United States. As an outsider who was born in the second half of the 20th century, it is hard to comprehend the determination of a small number of Native American servicemen who were not recognized as American citizens and did not have the right to vote, but chose to fight on foreign soil to defend America during World War I. The U.S. Congress granted Native Americans full American citizenship in 1924.

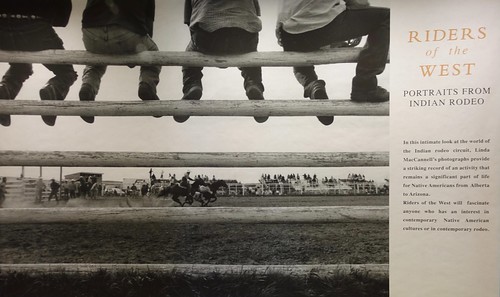

In another section of the museum, we strolled through a gallery labeled the Riders of the West: Portraits from Indian Rodeo. This traveling exhibit highlights a selection of Linda MacCannell’s black and white images on loan from the Center of the Southwest Studies at Fort Lewis College in Durango. Wild West rodeo shows became a popular attraction in the early 20th century while Native American rodeos often occurred during tribal cultural events instilling leadership skills and group identity. These images offer a small glimpse into this part of Western Native American culture.

On the second floor, we viewed a traveling exhibit that closed near the end of 2018. The Living with Wolves photographic exhibit used oversized photos to illustrate the life of wolves. Jim and Jamie Dutcher, Emmy Award winning filmmakers who documented the lives of wolves in the Sawtooth Pack on the edge of Idaho’s Sawtooth Wilderness, provided the photos and the Rocky Mountain Wolf Project (RMWP) co-sponsored the display. The RMWP has been exploring the option of reintroducing wolves into Colorado. In the 19th century, wolves were a vital part of Colorado’s landscape. According to the exhibit, the last wolf was shot in Colorado in 1945.

This exhibit included descriptions of the history of wolves starting with the fears derived from favorite European fairy tales to New World Folktales. These negative images were contrasted with the wolf’s positive image in Native American culture, where the wolf was always seen as an animal with great wisdom and as a spiritual guide. A chart illustrated how the lack of wolves in Yellowstone National Park from 1926-1995 negatively impacted the park’s ecosystem and how the reintroduction of wolves in 1995 positively affected the region. Through pictures and words, we gained a new appreciation for wolves.

Due to the museum’s off the beaten path location, many visitors choose not to make a detour. The drive is well worth the time and effort for travelers who would like to learn more about the indigenous people of the Four Corners region.

Sandy Bornstein, the History Comes Alive Through Travel Editor for Wandering Educators, has visited more than 40 countries and lived as an international teacher in Bangalore, India. Sandy’s award-winning book, May This Be the Best Year of Your Life, is a resource for people contemplating an expat lifestyle and living outside their comfort zone. Sandy writes about Jewish culture and history, historical sites, family, intergenerational, and active midlife adventures highlighting land and water experiences.

All photos courtesy and copyright Sandy Bornstein.