Note: This is the third in a series of articles on partourism (participatory tourism). The first two articles featured are Nepal Trekker Sponsors Orphans and Climber Adopts Village.

===================

From the host country's point of view, study abroad programs are the best form of tourism. One obvious reason is that students develop friendships, interests, and projects that keep them coming back.

The following account is adapted from a report by Pepper Etters, a former participant in my study/volunteer program; the report appeared in the Journal of Himalayan Sciences.

Pepper (far right) with (from left to right) Ngawang, Seth, and Empar

In the fall of 2000, I spent a month in the “sacred valley” of Rolwaling. According to Tibetan scriptures, Rolwaling is a beyul carved out and protected by tantric saint Guru Rimpoche (aka Padmasambhava) in the eighth century as a sanctuary for the preservation of Buddhist dharma during adverse times. Unlike other beyuls such as Shambala and Shangri-la, which have existed as purely mythological or literary sites, Rolwaling is and has always been recognized by its inhabitants and by those of neighboring valleys as sacred. This belief has contributed to an unusually strong cultural conservatism: until recently, for instance, it was unthinkable to slaughter an animal in the valley.

Sherpa festival

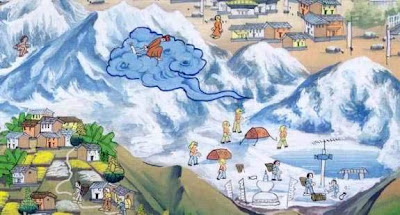

Painting of Rolwaling Valley: Detail of painting of Rolwaling Valley. Simigaon, at left, is a village at the confluence of the Rolwaling and Tamba rivers. The north wall of the valley is formed by Gauri Shankar, a sacred mountain once thought to be the highest in the world; Tibet lies beyond. To the right is the moraine-dammed glacier lake, Tsho Rolpa. The antenna device is part of a satellite warning system intended to give valley residents a bit of advance warning should the moraine give way. In the upper left is a yeti ("abominable snowman"); Eric Shipton took the iconic photos of yeti prints in the snow on Melungste glacier, just a couple hours scramble up from Beding, the main village in the upper Rolwaling.

I was there as a member of Bridges-PRTD ("Projects in Rational Tourism Development"), a private volunteer/study abroad company that was trying to help promote backpacker tourism as a resource for economic development. We were quartered at the main village of Beding (3700m), some thirty drab houses clustered around a small monastery about six days' trek up from the road head at Dolakha. At the time, there was no electricity, no functioning school, and no health clinic. The monastery was crumbling and the stupa had been washed away by a glacial lake outburst flood. Every able-bodied man and most of the women had left to work elsewhere as porters and guides, leaving only a few dozen women, children, and lamas to tend the fields.

Although our resources were limited, we did set up a handful of teahouses -- merely by helping design English-language menus and signboards; we bought some paint and lumber and gave the gompa a face-lift; we identified and marked a suitable waste disposal site; we gave a few lectures on first aid, and donated a trunk-load of medical supplies. A Kathmandu engineering firm was hired to produce a feasibility study and design for a micro-hydro plant.

After 2003, Bridges-PRTD suspended operations due to the political instability in Nepal. As often happens with small development efforts, we had raised hopes but failed to follow through with the kind of assistance that might make a long-term difference.

Rolwaling Valley, looking down from Tsho Rolpa (see next photo)

In October 2007 I was finally able to pull together an expedition of health care professionals with the objective of decisively upgrading healthcare facilities in Beding and sharing with this remote community the advantages of modern science. The team included my wife Jody Swoboda Etters, Medical Director Laurie Strasburger PA-C, Ken Zawaki MD, Ami Zawaki MD, Kristi LaRock PA-C, Clairane Vost RN, Tom Willard EMT, Vannessa Willard, Eddie Sandoval and Perry LaRock. Our support network included anthropologist Janice Sacherer, climber Nick Arding, Everest veterans Jon Gangdal and Dawa Chirri Sherpa of the Rolwaling Foundation, and Scott MacLennan and his staff at the Mountain Fund. Unlike the situation that prevailed back in 2000, when virtually no one had heard of Rolwaling, there is now an international web of individuals and groups interested in both the valley and its people.

On the trail north along the Tamba, not much had changed since 2000. The road had been extended to Singate, which meant we didn't have to deal with the 2000m descent (and ascent, coming back) just northeast of Dolakha.

Tsho Rolpa, the moraine dammed lake at the head of Rolwaling Valley

Rolwaling Valley; rhododendrons; Gauri Shankar to the north.

There were no signs of the sort of prosperity you see along the Everest trail -- the fact that Rolwaling had been closed to independent trekkers for thirty years meant that most visitors passed through in self-contained caravans, contributing precious little to the economy. The Maoist insurgency effectively removed the official restrictions on travel, but few tourists wanted to face being shaken down for a "contribution."

At our first stop, we happened on a man carrying his eleven-year-old daughter in a dhoko, a conical wicker basket supported by a tumpline over his head. They were coming from Simigaon, racing toward the hospital in Dolakha, although they had no money and were not optimistic about getting help. It turned out that the girl had a serious kidney infection. For two days we treated her with intravenous fluids and antibiotics. It was touch-and-go the first night, but when we parted ways she was walking and on her way to recovery. We were soon besieged by requests for medical assistance.

In Beding, there were signs of activity. A new stupa (Buddhist funerary monument) had been constructed, a new school built and staffed, and a rudimentary flood diversion project had been installed in the river. The Rolwaling Foundation was moving ahead with plans for a small hydropower plant to supply households with electricity as well as to develop local lodges so that independent backpacker tourism could finally take off.

After settling into the host families' homes, the team was welcomed to the village with a tea ceremony in which all the community members offered katas (ceremonial scarves) and blessings to the volunteers. Following the ceremony, we set to work. There was a side room attached to the school, and we converted that into a clinic, installing furniture and medical supplies. Solar panels provide light and charging capacity for small equipment, including a microscope donated by Colorado Mountain Medical, a clinic in Vail, Colorado. At the same time, we undertook public health improvements in areas such as sanitation, drinking water, waste management, nutrition and first aid training.

Meanwhile we were training Jangmu, the Nepali nurse hired to run the clinic on a long-term basis. Together we treated villagers for a variety of complaints. There were relatively few acute infections and injuries, while chronic and persistent disorders were much more prevalent. Respiratory diseases, cataracts, arthritis, tooth decay, gingivitis, and arthritis are all too common.

While we were able to deal with most problems, several could not be addressed without more advanced diagnostics. A few members of the community may have cancer and other life threatening illnesses, but without making the trek to Kathmandu, we couldn't be sure, much less provide effective treatment.

During the ten days we spent in the Rolwaling Valley, we also encountered a substantial demand for medical services on the part of tourists. Despite the fact that most packaged tours had medical supplies and trained staff, we were called on to provide assistance for quite a few cases of altitude sickness. As tourist traffic increases, we expect this need to increase.

Since our return, we have been looking for resources to address these issues and hope to bring volunteer specialists including dentists and oral surgeons, eye surgeons and orthopedists as well as additional general practitioners who will continue to train and support Jangmu and her successors so that they can continue to care for their community. Anybody who wishes to get involved in this project or offer support is urged to contact me at pepperetters[at]hotmail.com

The new Beding Clinic

Pepper Etters' advice for prospective visitors to Rolwaling

Outside of Nepal, and off the main trekking trails, you can't depend on English. There are many languages (not just dialects) in Nepal, but whatever their native language, most men and most children speak the national language. I would make an attempt to learn at least a little Nepali -- or hook up with someone capable of arranging lodging, food and other logistics along the trail.

Leave your tent and stove at home, and sleep in the tea-houses and lodges along the way. Some places won't have menus; just eat whatever they're preparing -- probably daal bhat (rice and lentils), with vegetables (tarkari) and achaar (chutney) if you're lucky. You may want to hedge your bets by bringing along some supplies as well. Instant soups become treasured moments on the trail. It really depends upon how you're traveling. If you're just out there to have a look around, you don't need a porter or guide; even if you're carrying your own load, however, a jar of nutella or peanut butter (or, if you're from Down Under, Veggie-Mite) can make a huge difference. Personally, when we head back, we'll be bringing several porter-loads of equipment anyway, so we'll stuff in some good cheeses, sausages, fresh fruits and veggies. Also, a few bottles of whiskey and wine for cold nights and well-deserved celebrations.

If you want to leave something with the Beding clinic, antibiotics, antiprotozoals and pain meds are cheap in Kathmandu. Avoid the urge to hand out pens and sweets to kids along the trail. Whatever you give will more than likely be sold and exchanged for candy. Remember, dental care is either medieval or non-existent out there. If you really want to make a difference, donate supplies directly to the schools along the way.

If you are considering some kind of philanthropic project, keep in mind that almost anything you start will require multiple trips. A lot of people end up dropping their project on the community's doorstep and leaving. Like those kids begging for sweets, entire communities quickly learn to expect bridges, clinics, schools and water taps from foreigners. They lose any motivation to develop facilities for themselves. If you don't have the time, patience or experience to start a project and follow through, there are a number of brilliant organizations to which you can donate time or money. These include www.dzifoundation.org, www.mountainfund.org, www.hesperian.org, www.heifer.org, www.globalnetwork.org, and www.pih.org. Or contact me about our next Rolwaling Medical Expedition.

=======

While Pepper Etters' work with Bridges-PRTD and with his own Rolwaling Medical Expedition had a significant impact on the Rolwaling community, his life too was changed. An accomplished river and wilderness guide as well as a photographer, Pepper seemed headed for a career as either a photographer or an academic. (See Adventurous Spirit, Etters' photography Web site.) Soon after completing his medical expedition, he entered training as a Physician's Assistant -- a move that was certainly motivated and probably facilitated by his Rolwaling experience.

Without casting aspersions on photography or academic research, which are inherently voyeuristic, I think it is worth pointing out that Pepper Etters has found in his highly participatory tourism the inspiration for a participatory career -- a career that will undoubtedly lead to further adventures in participatory tourism.

Seth Sicroff, Nepal Editor

Manager, Sunrise Pashmina

#StudyAbroadBecause

First six photos courtesy and copyright Seth Sicroff. Final photos courtesy and copyright Pepper Etters.