Travels in Europe: The Road to Rouen

The road to Rouen is paved with good inventions. Like that tiny weenie Jane, who every day crawls into the confines of our TomTom, which in turn sits on my windscreen and shows our course, although sadly, not always unerringly. Much to my chagrin, we have had words, Jane and I, and once to my eternal shame, I thumped her dwelling when she sent me off on a ring road in Reims, which like the catacombs in Rome, it takes you ages to get out of again. No, I am happiest when Jane transgenderifies and becomes Rowdy Yates, Keep rollin,’rollin’rollin ’though the streams are swollen, Rawhide … through rain and wind and weather, hell bent for leather, knowing my gal is by my side. Oh the joy of the open road and then a parking plot to peruse. But that is all ahead of us, on excellent, although not always well signposted French roads, for we reach Rouen by a circuitous route, eventually, but then press on a bit as well. Stay with me for the journey.

St Lo looked like a bog in the fog which encompassed it when we passed through, which was infinitely better than when the American air force passed over it in July 1944 and flattened it so badly, the French contemplated rebuilding it elsewhere, just leaving the ruins. As a US soldier was heard to say, “We sure liberated that place.” The setting, in a river valley, looked pretty, all the buildings new but like Patton’s forces in 1944, we pressed on, bursting out of the fog and into brilliant sunshine near Avranches. There we turned onto a back road, a little turner, through fields now shorn like a buzz cut head, the tarmac covered in slogans and symbols, and headed for a pimple on the horizon. The Tour de France had come this way.

A national treasure – by any measure

There are 3 million visitors to the Mont St Michel; we think a million were there on the day we arrived, and the summer was officially over! We parked the mandatory few kilometers away and walked some distance to a very efficient bus service which jammed like a tank full of tuna, deposited us several hundred metres from the entrance. We then trudged the boards to a drawbridge port, sighting more than a few damsels with dogs in distress. And there the fighting began, with hip and shoulder, thrusting with my camera bag, parrying with my Polo cap, hot and increasingly sweaty, assaulted on every side by lobbies of tack and bric a brac, postcards and ubiquitous restaurants promising crepes, waffles and Breton fare (Although the Mont is in Normandy, just!). Up and up we slithered on the wetted cobbles, sweat, or dog watering bowls spilled over, I know not, language at every turn till I said to my wife in my best Clousseau-nian, “Zis is too much. Zer is no reum to breez,” and we sought sanctuary in an eatery. The crepe was crap but the beer was a blessing.

Beautiful though the Mont might be, the only way we could enjoy it was to stay in a l’otel on the rock, of which there were an expensive few, so that when the daily tourist tide was swept back to the distant shore, there might be some serenity. There is now dredging to let the Mont become a true island again by 2015 and like Lindesfarne in the UK, leave the island numbers to the vagaries of the tides. The Mont wears its twelve centuries well and if we’d been able to see inside the abbey, I am sure that we would have been impressed. In 1851 a census showed 1182 people lived on the island, but then some were custodial invitees in the abbey turned prison, and while the views might have been spectacular, I doubt whether it would have been regarded as compensatory. In 2009, only 44 lived on the Mont. From the ramparts it looked to be an explorer’s delight, a magnificent sight, but a tourist blight. We accepted defeat and made our retreat.

Dappled Dinan in the noon-day sun – eating up the centuries

We headed for St Malo, where Jane and I had serious words. What part of centre didn’t she understand? A fort by Vauban, a glorious port, narrow streets, good beaches and fine Breton eateries, oh what promise! But the Mont crowd had now arrived in St Malo too, and the traffic sludge hardly budged, so we ‘chucked a uey,’ and silencing Jane, headed out of town and followed the signs to Dinan, and oh what a joy it was. A walled Breton town with an ancient port on the placid River Rance, with a stone bridge spanning the waters and the centuries, and a steep path to a castle keep protecting the medieval hilltop town. Many of the 13th Century buildings, the timber framed houses and the old Jacobin theatre from 1224, still stand. It being after noon, when so much of countryside France seems to close for a nap, the castle was closed too. Try getting a meal after 2.30pm and you come up with a big “Non,” no matter if it is a ravenous coach load from Mont St Michel, well unless you can find a place billed as giving ‘continuous service.’ They invariably do a roaring trade in tourists used to eating around the clock!

Well by now you are thinking why those fools went south when they should have gone north on the road to Rouen, and you are quite right, but it wasn’t all Jane’s fault. We were meandering and we asked her, politely, to take us back to Bayeux where we had a further night at the Campanile Hotel, a perfectly adequate budget boudoir for a bunch of Invasion Beaches oldies, with more hearing aids between them than smartphones, and who were in bed by 8pm after they’d had their steaks done in the blender! Quiet nights, early risers, my sort of people, with “Pardon” the most oft used word, and a cupped hand to an ear!

Next Morning we told Jane, “Caen, you” and soon we were outside the famous abbey of St Ettiene (The Abbey of the Men) where Guillaume le Conquéran, known to us as William the Conqueror, is buried. The 11th Century Caen-stone abbey was spared the destruction of most of Caen because some brave souls spread a sheet with a blood-soaked Red Cross in a courtyard and alerted the bomber crews that it was a sanctuary. As a result, the town has few interesting buildings and a wide pedestrian shopping mall where once timber framed houses stood. The foundations of William’s castle still remain inside the walls of a much larger castle, one of the largest castle grounds in Europe. After some shopping and a ghastly crepe filled with snow white, sick-making cream called a Courcheval, we were on the downhill run, and finally on the road to Rouen.

We chose the serpentine coastal road, bent on lunch in Deauville, the playground of Paris in the decadent twenties and thirties and on into the fifties and sixties, with its flash hotels, haute cuisine, casinos, beachfront dalliances, polo, and horse-racing. You pass a few attractive places along the way and over-ruling Jane, we meandered along the coastline past smart digs, tennis courts, and pony clubs, all the hallmarks of the posh with dosh, till seven kilometres from Deauville, we stopped at Villiers sur Mere, a flower bedecked eye-soother. After being turned away from a bistrot or two, we found a spot on the seashore. The sun shone and the wind whistled, although that had nothing to do with beach deportment or the apparent lack of apparel. Lots of blue stuff, with little wavelets, lots of yellow stuff for bods a-spreading, and lots of people in ‘our’ bistrot, gourmeting. And oh what a feast we had; divine lobster and entrecote, deep-fried Camembert, non-fattening, flavoursome frits and hand-fashioned vegies, and afterwards a crème caramel straight from the Bunsen burner. Beside and around us, the Bacchanal bubbled, the whole Creosote family at the table next door, snuffling into a barrel full of moules, more finger licking than in Fielding’s immortal novel, Tom Jones. And while they fumbled and fingered, we lingered, and too late thought of Deau, - oh oh, for Rouen called and it was quite plain that we needed Jane. “Straight there,” I said and she thought ahead, “Rouen coming up.” She sounded so confident.

Repetition is tedious, especially “Turn around when possible” if it comes when you are stuck in a traffic slug, on a bridge over the Seine, with rather punchy trams plying the tracks beside you. So we had words, shouted words, then silence, she, I, and wife, and I knew I was in strife, maybe even a stake tonight! Rouen comes with an impossible main street, Rue Jeanne D’Arc, naturellement, which every ten or so metres had either a traffic light or a crosswalk. Like a pathfinder, I headed for the cathedral, but Rouen also has the most diabolical one-way street system and the Mercure Hotel believes on saving money on directional signs. At one point, I chose left just as she yelled right and like main-line buses, none for hours and suddenly three, I was bustled on by three cars at my back bumper, verisimilitude-in-spades coming from she to my right, who is always right! And round the whole bloody block we went again, 25 minutes, Rouen ruddy-well ruined.

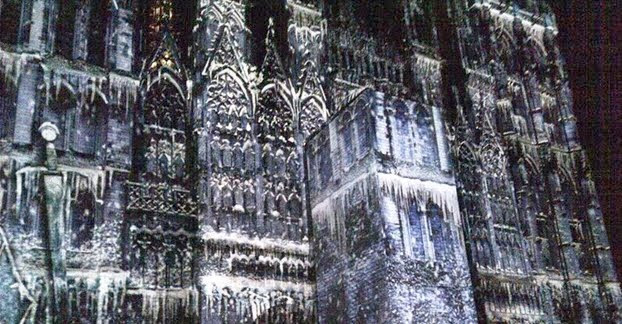

A beer and a whine in a bistrot and civility was restored, Jane forgiven too. Later that night, the sound and light show, which did not kick off till 10pm, was just spectacular, using as a backdrop, the front of the Rouen Cathedral. A church has stood there from the 4th Century and the subsequent cathedral was visited by Charlemagne in the 7th century, although the current Gothic style cathedral dates merely from the 12th Century! Suddenly the cathedral would be encased in green jungle creeper, a waterfall erupted from its spire, playing cards were built against its edifice and suddenly collapsed, snow came and a winter mantle, lots of ooohs and ooohs. In the morning we visited the cathedral, like others, tilting our heads backwards to the high vaulted ceiling, the enormous transept, the exalted high alter from where the voices of Archbishops would have coiled around the pillars as the voice of God himself. The RAF also managed to bomb it during WWII (fortunately not too badly, but then Rouen was an important river and rail junction) and Richard the Lionheart is buried there. And that man Monet painted it many times and in many lights, as was his want.

Rouen Cathedral with a ‘sudden mantle of snow’

In the morning, while the chill of l’automne was upon us, my wife set out for Printemps, and I as a parader of the lost Arc. And find her silver spike I did, the place of the stake where she had been burned – twice, to make sure, before her ashes went into the Seine. She has remained a symbol to the people of France, admiring her spirit, bravery and pluck, her symbolic needle like stake at the edge of a now bustling market. It was after all, the English in Rouen that had done for her, the English church that claimed her a heretic.

Around the edges of the market, there are still many half-timbered buildings, most leaning, with the weight of ages, on each other, or precariously overhanging into the street. They date from the times of Rouen’s turbulent past, when it was the largest medieval city in Europe. The Romans had been there, the Vikings and the Prussians, all as conquerors, all seizing the strategic position on the Seine, its 16th Century astronomical clock still fully functional, recalling much in silence. But time was passing us by, we had briefly seen brief bits of Rouen, and the roses were still shining in Picardy. We saddled up Jane and said farewell to Jeanne, … keep rollin, rollin, rollin.’ Off to see life in the bubble.

Picardy, Picardy, the rich red fields of Picardy, the blood of youth spread there by a war that one hundred years on, was not regarded as having been ‘necessary’ and that everyone was sucked in by national pride, a war so horrible that it was set to end all wars. The Somme, synonymous with the machine gun, slaughter, trench warfare, and tunneling in the soft chalk soil that underlays the undulating hills and the fields of beet sugar, village churches so close to each other, that you could sting a wire between steeples and Blondin could wire walk it while the crowds picnicked below. Places where farmers are artists with a tractor, the plow their palette, the scythe their spatula, the greens of beet and corn blended with the brown of tilling strips, squares and oblongs, giant esses. There are rolls of hay, and haystacks too, the sort which in the movies usually have a car bursting right through them, and we all laugh, the occasional cows, the inevitable silos, a sight familiar to every Aussie kid who ever travelled through the Wheatbelt, and at times I felt right at home.

And in Villers Brettoneux, Australians are ‘at home’, for the Australians had fought there in April 1918, and 770 sons lie buried in the soil. Troops plugged a hole in the line and drove out a force of Germans ten times their number, Germans who thought they were at the cusp of campaign victory after years of stalemate, but were pushed back to their starting line and six months later, sued for an armistice. We saw Rue Sydney and Rue Melbourne and the sign at the school, Never Forget the Australians, and we felt that reflected pride when we had lunch at the Café Victoria and the drizzle fell all around like a shroud.

On the road again the sky was malevolent as we crossed the several strands of the Somme, skirting around St Quentin as though it was a prison. Then it was over the Oise River, the clouds morose and laden with spittle, dropping indeed as a “gentle rain from heaven,” but as soon as we had got used to the wiper tango as we neared Reims, with its great cathedral where 30 of France’s Kings had been crowned, the sun came out punching, and Jane, I think probably overcome by the dazzle, sent us into Reims in peak hour. We simply left her in the car that night.

Late in the afternoon at the Chateau de Etoges in the Champagne region

The Chateau d’Etoges was constructed as a fortified manor/castle at the start of the 17th Century and was the headquarters for the Prussian General, Blucher in 1814 during the battle of nearby Champaubert (there is a column monument and a ring of cannon), some six kilometres from d’Etoges. While Napoleon won that one, he soon was forced to surrender and sent into exile in Elba. It was a plush chateau indeed with beautiful sitting and drawing rooms, peaceful gardens disturbed only by the quacking of ducks in the moat, and the crunching of tyres of the stately old Alvis’ and Bentleys – and no doubt our People’s Peugeot. The statuesque Front Desk manager, beautifully coiffured and dressed, brought us a glass of champagne in the garden. Wendy felt right at home.

We nested in the Orangerie in a lovely room and dined that night in the decidedly snooty, expensive but delightful restaurant, where the food and wine was first class and the selection of local cheeses would satisfy any turophile (Connoisseur of cheese). The staff were a mixture of enthusiastic whelps whose rushing demeanor conveyed a measure of discomfort, while the most professional of their party, an older man from the villages of Etoges to be sure and dressed in a circa 1930’s suit, came with a stoop, lurch, and a tick, with a leer that was a mix of Dr Strangelove and Dracula, but boy he knew his wines and cheeses The following night though, we ate al fresco in the garden, seated sideways on a settee, our Languedoc wine a few Euros in the supermarket, so too some quintessential bread and a runny cheese that we would have had to chase to Epernay if it had got out of the grounds! Both meals were memorable, and the swans and ducks joined in for the latter. We were sorry to leave, and probably so too were the ducks.

In the morning we rose at luxuriating leisure and headed through some of the small villages, the suppliers of Premier and Grand Cru grapes, in to Epernay for breakfast. Wrong. Food was not served till noon in the bistrots ringing the southern half of Place Charles de Gaulle, but a great coffee was available and with a patisserie not far away, I bought a flan full of fruit, and we cocked a snoot and ate it there, feeling rather sated to boot! Just time for a free champagne taste at the local Tourist Bureau (Closed at 1230 on a Saturday, like much else, but the parking meters kept working!) and then had a short walk along the Rue de Champagne, a sort of Board Member-like gathering of some of the famous Champagne houses all in the one Rue. And right at the beginning was not only Moet’s acquired mansion, but also the headquarters of the whole Moet and Chandon shebang. Underneath it all, 28 kilometres of caves for bottled bubbles, including the fabled instantly recognizable bottles of Dom Perignon, the monk whose discovery invented ‘champagne’ for the world. Mind you, others of Verve decided to stay with their Mumm in Reims, but nothing could take away from Epernay the epithet to be the Champagne capital of the world.

Wendy rushed to get me from the loo. There were cancellations, hurry! Tasting two vintages too, come ON!

Wendy, at the Gates of Heaven!

In the Champagne region it rains 200 days a year so the chalk remains cool and wet to the touch, perfect for ‘growing’ little babies cham! The cellars contain 28 million bottles and each is hand or machine turned with machines turning 100,000 per day and a good hand turner 50,000 so that the bottles are fully rotated every five to 6 weeks to move the sediment, sugar, and yeast. Before each bottle is fitted with its permanent cork, the neck is snap frozen at -27 degrees, and the juice plug extracted. The cork that you and I then remove, or fire into the air in celebration, is then fitted. The Dom is, of course, all turned by hand and it is 12 years before any bottle is released. They will next year release a hundred year old Dom and we were told that the excitement was mounting with every annual proof tasting, for it is, figuratively, an exceptional champagne. I wondered if the bottles became disoriented with a lifetime of turning or the turners got arthritis, or indeed whether they continued the turning motion of the hands in their sleep, possibly to their partner’s chagrin!

At the end of the tour we tasted before the assembled M&C family, all aligned with military precision from a Demi (half a litre) through to a Nebuchadnezzar (at 20 litres) although there is too in the champagne world, a Melchizedek which comes in at 40 litres and is presumably gift wrapped with a block and tackle, six lifters and safety helmets as protection against the artillery shell sized cork if fired in celebration! We tasted two seven year old vintages, a white and a Rose although I, as not a great imbiber of bubbles, sipped only half flute, but Wendy ensured that not a drop was wasted. Just time for a sandwich lunch (Jacques Kerbside Diner was all we found open) and then back to the chateau for a rest, and some gateaux, then into the great house with a book, to a comfortable nook. Oh yes, I could easily live as an aristo-cat, purr, purr, purr.

Eyes agape in the vale of the grape. A Champagne valley near Epernay

We left the next morning when the sky was rouge, for we had many miles to go to Bruges. Jane sent us back through Picardy. The wind had thickened, the rain came too … we gave her the cold shoulder and followed the signs which said Brugge. Farewell Froggies, hello Flems.

Winfred Peppinck is the Tales of the Traveling Editor for Wandering Educators

All photos courtesy and copyright Winfred Peppinck