Houston, the country’s fourth largest city, boasts dozens of museums. But only one is worth its weight in gold. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston is currently a treasure trove of Egyptian artifacts due to a groundbreaking exhibit.

Titled, “Tutankhamun: The Golden King and the Great Pharaohs,” the exhibition beckons visitors to travel through 2,000 years of Egyptian history. It highlights “King Tut,” Egypt’s youngest and most famous pharaoh within a historical context. Egyptian archives reference 300 pharaohs and 31 dynasties.

On display through April 15, the exhibition begins inside a dark, mysterious room. A foreboding but familiar voice briefs visitors on what’s to come. Narrated by Oscar-winning actor Harrison Ford, the video sets the tone for an extraordinary adventure.

The journey begins dramatically when the doors swing open to reveal a replica of the Great Sphinx at Giza, represented by King Khafre, the pharaoh who built it. Khafre ruled from 2558 to 2532 BC. He was succeeded by his son, Menkaure, whose statue is also displayed.

Next up and on display is a marble statue of a ruler from the 18th Dynasty, Thutmose III. He ascended the royal throne of Egypt in 1504 and ruled until 1452 BC. The statue of Thutmose III was found in Deir-el-Medina.

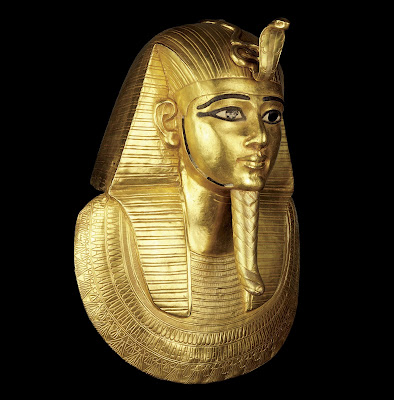

Amid the abundant collection is the statue of Hatshepsut, the first woman in Egyptian history to assume the regal title of pharaoh. A definite show stopper is the gold funerary mask of “The “Silver Pharaoh,” King Psusennes I.

Funerary Mask of Psusennes I - The golden mask lay over the head, chest and part of the shoulders of the mummy of Psusennes, as a layer of protection. The royal headdress with ureaus cobra and the divine false beard he wears attested to his royal and godly status. The use of gold, considered the flesh of the gods, reaffirmed his divinity in the afterlife

Psusennes I’s royal burial chamber was discovered, with less fanfare than King Tut’s, in 1939 by French archaeologist Pierre Montet. The Psusennes I discovery is noteworthy because he’s the only king who has ever been found entombed in a silver sarcophagus. In fact, so important is the forgotten discovery, that the Public Broadcasting System aired an in-depth report on “The Silver Pharaoh” on Nov. 3, 2010.

This traveling exhibit, whose curator is Dr. David P. Silverman, includes not only Psusennes I’s gold funerary mask but more than 100 ancient artifacts never before seen in any exhibit in the United States.

Additionally, a towering 10-foot statue of King Tut will inspire awe in most visitors. The “boy king,” so christened because he ruled from the age of nine to 19, ruled Egypt from 1333 to 1323 BC. The original King Tut statue stood nearly 17 feet high. It was one of two statues that guarded the entrance of the funerary temple in the Valley of the Kings.

King Tut

The exhibit is organized by the National Geographic Society in conjunction with Arts & Exhibitions International and AEG Exhibitions. Much of the exhibit proceeds go toward preserving Egyptian antiquities and monuments. Proceeds are also helping to build a new Grand Egypt Museum in Giza.

Tutankhamun, son of Akhenaten, was the last ruler of the 18th Dynasty. King Tut’s untimely death at 19 was shrouded in mystery. He lay in his tomb for more than 3,000 years before being discovered by British archaeologist, Dr. Howard Carter in 1922.

Dr. Carter’s amazing discovery, with financial backing from Lord Carnarvon, made headlines around the world. Now, dim lights and black-and-white vintage poster-sized photos chronicle the event and help viewers share in Carter’s exhilaration.

Visitors can see for themselves the condition in which Carter found the Ante chamber, the first of four separate chambers protecting the pharaoh’s tomb. Moreover, more than 5,000 objects were found in the royal burial site.

Finger covers Gold Carter 256ll These golden covers, or stalls, were found on the fingers and toes of Tutankhamun's mummy, and they served a function similar to that of the amulets that protected other parts of the king's body from various magical dangers. The precious material of which they were made also identified the king with the god, whose flesh was thought to be of gold. -Zahi Hawass

Undaunted by the numerous gold objects and artifacts, Carter blazed a trail from the Ante chamber to the Annex, then the Treasury, and finally the Burial chamber. In the Burial chamber Carter discovered the mummified remains of King Tut.

Seven beds were among the staggering number of items found in the youthful king’s tomb. One of the beds, hand-woven in reed matting, is on display inside a glass case. A few steps away, visitors can see a small, intricately-carved chair also believed to have belonged to the boy king.

Other artifacts sure to impress are King Tut’s golden sandals, which were still on his mummy when he was found. The sandals are displayed in a glass case alongside golden replicas of fingers and toes, sure to raise eyebrows.

Tutankhamun’s Golden Sandals - These golden sandals have engraved decoration that replicates woven reeds. Created specifically for the afterlife, they still covered the feet of Tutankhamun when Howard Carter unwrapped the mummy.

Attendees learn the replicas were coverings slipped over the body’s real fingers and toes during the mummification. The beauty of the exhibit, aside from the unique golden ornaments and statues, is the wealth of information on Egyptian history.

Secretary General of Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities, Dr. Zahi Hawass, has spent a lifetime exploring the enigmas surrounding the boy king. One question that had dogged Hawass until recently was the mystery of how King Tut died.

Now Hawass, the eminent archaeologist, has lent his raspy, accented voice and extensive knowledge of Egyptian history to the exhibit as he accompanies legions of visitors through strategically-placed videos.

For exhibit-goers, this sojourn is a total immersion into Egypt’s history, customs and religious beliefs. Through written posters and rented audio devices viewers are mesmerized by the artifacts they see and the tales they hear.

Patrons who rent an audio device will hear Ford and Hawass take turns explaining the significance of some of the artifacts. With a click of a button, visitors hear about 22 historically important pharaohs, their queens, customs and the like.

Nevertheless, an audio device is not mandatory to learn about ancient Egypt. Literature, pictures and short videos are displayed at every turn. Organizer even pitched a tent to help attendees feel as if they were part of Carter’s big dig. But for those who want more, the cost of the audio device is $2.50 for MFAH members and $7.50 for non-members.

Thanks to well-placed information, visitors learn that embalmers routinely removed the liver, lungs stomach and intestines of deceased royals. It was believed the organs would be needed in the afterlife. The organs were stored separately in individual mini coffins.

It’s thought provoking to see the tiny, golden canopic coffinette that once held King Tut’s stomach. No explanation is given as to the whereabouts of his other organs. But since King Tut’s mummy still resides in the Valley of the Kings, his organs may still be there as well.

Canopic Stopper - A large container with four hollowed out sections held the internal organs of the king. Each of its compartments had a lid in the form of Tutankhamun’s head. The royal name on both the chest and its outer shrine appears original, suggesting that Tutankhamun did not usurp the container from a predecessor.

Among the dozens of items in this exhibit are ornate gold rings, a pet’s sarcophagus and a regal gold collar that belonged to Neferuptah, daughter of Amenemhat. King Amenemhat ruled in the 12 Dynasty from 1860 to 1814 BC.

But those artifacts pale when compared to the contents in the Burial chamber. Here is a replica of King Tut’s mummified remains. The mind boggling display is protected by a glass casket. King Tut’s bare skeletal remains look as if they’re lying in state.

A film, perched on a wall across from the remains, shows a team from an Egyptian research project conducting a CT Scan of King Tut in 2010. The film, along with King Tut’s mummy replica, is sure to make attendees feel that this is a fitting climax to an extraordinary journey.

The CT Scan ruled out murder as King Tut’s cause of death. Instead, the final conclusion was that he probably died of natural causes, such as malaria and an infected leg wound. Ironically, despite efforts by his enemies to purge him from Egypt’s history, King Tut remains the most famous pharaoh in history.

Tutankhamun Shabti The only such figure found in the Antechamber, it is one of the largest of the servant statuettes. The inscription records the shabti spell from the Book of the Dead, ensuring that the king would do no forced labor in the afterlife.

This is the second National Geographic Society exhibit focusing on King Tut and Egyptian history. The other, “Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs,” was hosted by the Dallas Museum of Art in 2008. That exhibit did not include many of the items now on display in the monumental MFAH exhibit.

The exhibit at the MFAH is a once-in-a-lifetime must-see event. Advanced planning is recommended because visitors are only allowed into the exhibit every 30 minutes. Adult tickets for MFAH members are $23. Seniors and students are $22. Children under five are admitted for free.

Adult tickets for non-members are $25 on weekdays and $33 on weekends. For information visit: mfah.org or kingtut.org If you prefer, call 1-888-931-4TUT (4888).

Colossal Statue of Amenhotep IV / Akhenaten - Numerous colossal sandstone images of Amenhotep IV enhanced the colonnade of the king’s temple to the Aten at East Karnak. The double crown, atop the nemes-headdress, alludes to the living king as representative of the sun god.

Rosie Carbo is the Lifestyles Editor for Wandering Educators

Photos courtesy and copyright Sandro Vannini