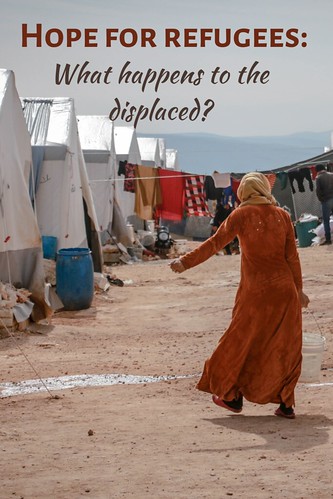

Imagine yourself pushed out from the place you have called home all your life—with only a bag containing everything you have managed to save, not knowing the next place you will lay your head, having to move to another state, country, or continent to begin to piece your life back together again. This is a reality for people all around the world, in circumstances much worse than we can ever imagine.

When a terrible disaster occurs, such as war, urban conflict, a pandemic, tsunami, flood, or an earthquake, it is usually quantified by the number of deaths suffered from the incident or the extent of destruction recorded—and sometimes the number of displaced persons or destroyed properties.

One such instance is the Covid -19 pandemic; the World Health Organization as of 11th September 2022, has recorded over 6.5 million deaths caused by the virus.

Another is the Russia/Ukraine conflict, which has killed around 5,800 civilians and displaced more than 8 million people.

The United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) reported that over 742,000 Rohingyans have fled their country, Myanmar, as a result of the civil war.

Syria alone has recorded around 13 million people who have been displaced from their homes since the beginning of the Syrian civil war began in 2011.

In 2022, the Pakistan flood destroyed around 1.6 million homes, and 7.6 million people have been displaced.

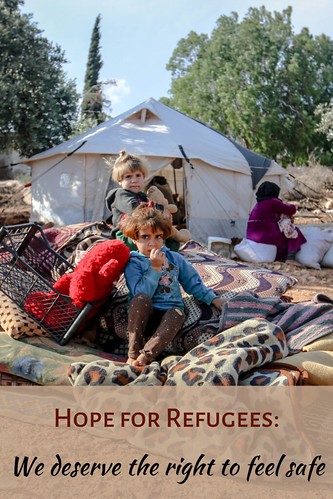

All around the world, it is estimated that 89.3 million people have been forced to leave their homes at one point or another—half of which are children.

Any time I come across stories and statistics like these, the questions that come to mind are myriad:

• Where are these displaced people?

• What happened to them?

• Did they finally find a place to call their home, or were they able to return to their former homes?

Displaced persons are usually forced to leave their homes, loved ones, or properties due to armed conflict, disasters, or violence. Based on the circumstances of their flight, they oftentimes do not have the necessary documentation or adequate finances to set up a comfortable place to call home, either within their country or in another country.

In this article, I will explain what forced displacement is and then outline the difference between the terms refugee, asylum seeker, and internally displaced person. I will also share some alarming statistics to paint a picture of how dire the refugee crisis can get if not managed well.

Internally Displaced People

People forced to flee their homes and move to another place within their country are called internally displaced persons (IDPs). IDPs are defined in the Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement as “persons or groups of persons who have been forced or obliged to flee or to leave their homes or places of habitual residence, in particular as a result of or in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict, situations of generalized violence, violations of human rights or natural or human-made disasters, and who have not crossed an internationally recognized border.”

Although IDPs are generally recognized by United Nations High Commission for Refugees, they are not awarded any special rights other than the human rights all humans enjoy. Since they are still within the territory of the state of conflict or violence, they receive no international protection. Every country has the sole responsibility to protect, fulfill, and promote the human rights of the IDPs within its state. Consequently, IDPs are faced with incredible challenges, such as being confined in the conflict areas, being used by the insurgents or even the states as targets, becoming kidnapping victims, being exposed to physical and sexual abuse, and having no access to necessities such as food, water, and shelter.

The Global Report on Internal Displacement in 2021 states that as of the end of 2020, 55 million people have been internally displaced, 48 million of which were a result of conflicts and violence, while 7 million were a result of disasters.

One thing you can be sure of is that the numbers are sure to increase with the current disasters and violence happening all around the world. It is also important to point out that more than 70 percent of this number is comprised of women and children.

Refugees and Asylum-seekers

Another group of people who flee their homes from persecution may seek refuge on the shores of another country. These people are referred to as refugees. Though the term refugee is commonly used to describe asylum seekers, refugees, and migrants, each has its own definition and characteristics.

The 1951 Refugee Convention defines a refugee as “someone who is unable and unwilling to return to their country of origin to avail herself of the protection of her country of nationality owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.”

An asylum seeker, on the other hand, is a person who has fled their county for another country seeking protection from their well-founded fear of being persecuted but is yet to be declared a refugee. In other words, the person has applied to be declared a refugee, but the government of the host country is still processing the claim of the applicant and has not yet declared them a refugee.

The difference between an asylum-seeker and a refugee is important to determine what each is entitled to. When a person is declared a refugee by a host country, the country is obligated to ensure that the human rights of the refugee are protected; the country is also obligated not to forcibly return any refugee to the territory where they may reasonably fear persecution or discrimination. This is known as the principle of non-refoulement.

The United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) was established to ensure states respect their obligations under the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees by monitoring the treatment of refugees and asylum-seekers and providing support to the states when their resources are insufficient. This means that a refugee has international protection and has the right to work in a host country, has their freedom of association and movement guaranteed, and is protected from torture and discrimination in the host country same as every citizen.

According to UNHCR global trends 2021, at the end of 2021, the number of refugees under UNHCR’s mandate was 21.3 million, and the number of asylum seekers was 4.6 million.

One of the most interesting facts is that 83% of all forcibly displaced persons are hosted by low and middle-income countries.

The countries with adequate resources and finances to aid these refugees, more often than not close their borders and treat the asylum-seekers as criminals. Some people have argued that asylum-seekers are treated worse than criminals because all convicted criminals know their terms of the sentence while this is untrue for asylum seekers. It is quite common to hear that most countries create detention centers for asylum seekers and detain them indefinitely while they process their claims and application.

We should always have in mind that through no fault of theirs, their homes and properties were destroyed, their loved ones were murdered or abducted, their finances and documents were lost. That they fled to different places in search of refuge—and no matter where they pass through or end up in, whether in their own country or outside their country—they should not be punished for it.

As it has been seen countless times, displacement can happen to anyone in any part of the world or at any status in life. 1 in every 88 persons has been forced to flee their home at one point or the other.

I call on us all to be more welcoming, more aware, more accommodating, and more encouraging to anyone around us that have been displaced from their home. In my next article, I will discuss the limitations of the 1951 Refugee Convention definition of a refugee and the consequences of those limits in real-life situations.

Read more in this series:

Sandra Okafor is the Refugee and Forced Migrants human rights editor at Wandering Educators. She is currently studying a Master's in Human Rights and Diplomacy at the University of Stirling. She is motivated by the desire to impact knowledge and to empower others in creating a better world.