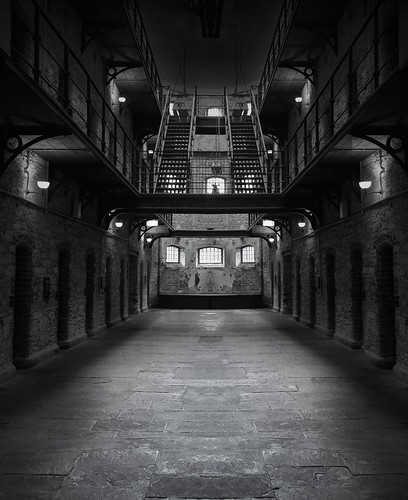

Are Americans inherently conditioned to be criminals? Are we raised to wreak havoc on our communities by breaking the laws that are in place to protect us? My short answer is no. However, when looking at statistics, it is alarming that America is known as the world’s prime jailer. “Representing just 5 percent of the world’s population, we now hold 25 percent of its inmates. The “tough on crime” politics of the 1980s and 1990s fueled an explosion in incarceration rates. By the close of 2010, America had 1,267,000 people behind bars in state prisons, 744,500 in local jails, and 216,900 in federal facilities—more than 2.2 million people locked in cages.” (sic) (ACLU)

According to the ACLU, “Blacks are incarcerated for drug offenses at a rate 10 times greater than that of whites, despite the fact that blacks and whites use drugs at roughly the same rates.”

There are many people who state that racism is over, or deny that it is currently an issue in America - despite facts showing that blacks are targeted at a much higher rate than whites. Mass incarceration has had an overwhelming effect on minorities in the United States of America by becoming a modern day form of slavery.

The War on Drugs has played a major role in minority communities. According to the ACLU, “Drug arrests now account for a quarter of the people locked up in America, but drug use rates have remained steady. Over the last 40 years, we have spent trillions of dollars on the failed and ineffective War on Drugs. Drug use has not declined, while millions of people—disproportionately poor people and people of color—have been caged and then branded with criminal records that pose barriers to employment, housing, and stability.” Forty-six years ago, President Richard Nixon coined the phrase “War on Drugs.” This declaration of war brought about a new set of drug laws and penalties in the American justice system. “The iconic case of the punitive US war on drugs is the one waged by the federal government. The federal jurisdiction metes out arguably the harshest drug sentences for otherwise-similar offenses of all US jurisdictions, largely as a result of dramatic changes to sentencing statutes made by Congress in the 1980s. Most infamously, those statutes mandated especially long prison sentences for those convicted of crack cocaine crimes, the vast majority of whom have been people of color.” (Lynch 178)

The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 made a major change to sentencing guidelines in regards to crack cocaine. “Under the 1986 Act, it took a trafficking offense involving 500 grams of powder cocaine to trigger a mandatory minimum sentence equal to that involving 5 grams of crack cocaine. Two years later, Congress intensified its disparate treatment of crack: a provision of the Omnibus Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988 specified that mere possession of crack cocaine triggered a mandatory prison sentence of five years whereas no other possession offense required a prison sentence at all (a maximum of one year was specified).” (Lynch 180)

These harsh sentencing laws made imprisonment rates increase at a rapid growth rate. There was an increase in criminal cases, which led to more prison sentences - and people were being incarcerated for longer periods of time. Average sentence lengths more than doubled after the strict laws were put into place.

“The impact of drug policy on Blacks has been described as American apartheid, a new Jim Crow sociolegal system creating a new form of slavery and racial segregation. Employing mechanisms of a systemically, racially biased system—from policing methods, to courtroom sentencing, to long-term prison warehousing—the war on drugs is seen by many as a tool to enforce White societal dominance by creating and sustaining a racialized (largely Black, young, male) underclass, disenfranchised and barred from societal participation.” (Eversman 32)

There are many residual effects that linger after a person is released from prison with a felony on their criminal record. They have lost time in society, which often leads to a feeling of displacement. Technology changes, skill requirements, and education necessary for gainful employment are often lost on those who have been incarcerated. They are no longer eligible for a Pell Grant to pursue earning a degree. Many employers have a no felony/no misdemeanor policy, which means that if you have a previous conviction on your criminal record, you are automatically not eligible to work for them - even if you are the best candidate, skill- and education-wise. Oftentimes, people that are released from prison are not truly free, even though they served their time for their crime. They are kept on probation or parole, which requires them to maintain a strict reporting schedule. Employers are not flexible with employees having to leave work to meet with their parole officer during work hours or to take a mandatory drug screen on a weekly basis. They are also required to pay their restitution, monitoring fees, court fees, and testing fees. If payments are not made timely and in accordance to the terms set by the court, then they are placed back in jail for violating the terms of their probation. “While large numbers of inmates are released from prison every year, a high percentage of them return in a short time. In 1994, the most recent year for which data is available, approximately sixty percent of those released from prison were rearrested for a felony or serious misdemeanor within three years, with over twenty-five percent sentenced to prison for a new crime.” (Williams 531)

“Michelle Alexander’s book, The New Jim Crow, advances the theory that, in today’s colorblind era, police, prosecutors, judges, and legislators use criminal history as a proxy for race, thereby establishing (or maintaining) a racial caste system. During the Jim Crow era blacks were discriminated against, disenfranchised, excluded from juries, prevented from bringing legal challenges, and denied other civil, political and legal rights. The same can be said today about felons, a disproportionate number of whom are African-American. Alexander asserts that in the era of mass incarceration, a newly freed felon has scarcely more rights, and arguably less respect than a freed slave or a black person living free in Mississippi at the height of Jim Crow.” (Butler 1048)

The state of Louisiana is known as the world’s prison capital. “In the early 1990s, the state was under a federal court order to reduce overcrowding, but instead of releasing prisoners or loosening sentencing guidelines, the state incentivized the building of private prisons. But, in what the newspaper called "a uniquely Louisiana twist," most of the prison entrepreneurs were actually rural sheriffs. They saw a way to make a profit and did. It also was a chance to employ local people, especially failed farmers forced into bankruptcy court by a severe drop in the crop prices. But in order for the local prisons to remain profitable, the beds must remain full. That means that on almost a daily basis, local prison officials are on the phones bartering for prisoners with overcrowded jails in the big cities. It also means that criminal sentences must remain stiff, which the sheriff's association has supported. Writing bad checks in Louisiana can earn you up to 10 years in prison. In California, by comparison, jail time would be no more than a year. There is another problem with this unsavory system: prisoners who wind up in these local for-profit jails, where many of the inmates are short-timers, get fewer rehabilitative services than those in state institutions, where many of the prisoners are lifers. That is because the per diem per prisoner in local prisons is half that of state prisons. In short, the system is completely backward. Lifers at state prisons can learn to be welders, plumbers or auto mechanics-trades many will never practice as free men-while prisoners housed in local prisons, and are certain to be released, gain no skills and leave jail with nothing more than "$10 and a bus ticket." These ex-convicts return to the already struggling communities that were rendered that way in part because so many men are being extracted on such a massive scale. There the cycle of crime often begins again, with innocent people caught in the middle and impressionable young eyes looking on. Louisiana is the starkest, most glaring example of how our prison policies have failed. It showcases how private prisons do not serve the public interest and how the mass incarceration as a form of job creation is an abomination of justice and civility and creates a long-term crisis by trying to create a short-term solution. It is a prison system that leased its convicts as plantation labor in the 1800s has come full circle and is again a nexus for profit.” (Blow 14)

Inmates are used as a cheap form of labor, as employers do not have to pay any benefits for them to be employed. “What was once a niche business for a handful of companies has become a multibillion-dollar industry . . . The prison-industrial complex now includes some of the nation’s largest architecture and construction firms, Wall Street investment banks that handle prison bond issues and invest in private prisons, plumbing-supply companies, food-service companies, health-care companies, companies that sell everything from bullet resistant security cameras to padded cells.” (Deckard 11)

It becomes apparent that the prison system and the current state of mass incarceration in the United States targets our minority population. The U.S. being considered The Land of the Free is certainly debatable.

Works Cited

Blow, Charles M. "Louisiana for-profit prisons are abhorrent." Indianapolis Business Journal 18 June 2012: 14C. Business Insights: Global. Web. 24 Mar. 2017.

Butler, Paul. “ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF RACE AND CRIME.” The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology (1973-), vol. 100, no. 3, 2010, pp. 1043–1060

Deckard, Natalie Delia “Prison, Coerced Demand, and the Importance of Incarcerated Bodies in Late Capitalism” Social Currents, September-22-2016, Vol 4, Issue 1, pp. 3 - 12

Eversman, M. H. ""Trying to Find the Middle Ground": Drug Policy and Harm Reduction in Black Communities." Race and Justice 4.1 (2013): 29-44. Web.

Lynch, M. "Theorizing the role of the 'war on drugs' in US punishment." Theoretical Criminology 16.2 (2012): 175-99. Web. 14 Mar. 2017.

"Mass Incarceration." American Civil Liberties Union. N.p., n.d. Web. 14 Mar. 2017.

Williams, Kristen A. “Employing Ex-Offenders: Shifting the Evaluation of Workplace Risks And Opportunities from Employers to Corrections. UCLA Law Review, Vol 55, Issue 2 (December 2007), pp. 521-558

Kelly Ann Dey is a champion for social justice and advocates strongly for equality. She is currently employed in the Department of Economics at Western Michigan University and is also pursuing her Human Resources degree at this time. Kelly is passionate about encouraging students and staff to continue to educate themselves on matters of social justice. Kelly Ann Dey resides in Kalamazoo, Michigan.