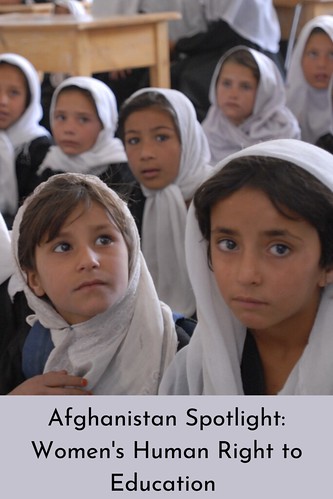

On 30th August 2021, the US military departed from Afghanistan, ending a 20-year occupation, which led to the ongoing Taliban takeover. As the current events in Kabul continue to unfold, the reality of the impact of women’s human rights in Afghanistan becomes more of a threat as each day passes.

This article, as part of a series on women’s human rights in Afghanistan, will focus on the topic of education and how the denial of this basic human right for women could suggest only the start of restrictions on women’s rights in Afghanistan.

The Right to Education (Article 26 of the UDHR)

In The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 26 states that everyone has the right to education. As women in Afghanistan are under restrictions from both attending or teaching education, their basic human right to education is under danger.

Current Events

As of late September, the Taliban Islamic Emirate government continues to systematically remove women from public spaces, just over a month since the overtaking of the Capital of Kabul.

While the initial responses from the Taliban suggested that it would not replicate the fundamentalist policies of the previous Taliban government, the current actions being carried out in Afghanistan suggest otherwise.

On 18th September 2021, the Taliban replaced the women’s ministry, MOWA, with the all-male Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice. This action taken by the Taliban evidences another restriction of women’s progressive rights since the previous Taliban takeover.

It has further been reported that female employees in the Kabul city government have been told to stay home.

The Women's Affairs Ministry (MOWA) has not only been shut down, but the building has been repurposed by the Vice and Virtue Ministry. On 18th September, MOWA staff were escorted from the building, notes Sharif Akhtar from the World Bank's 110 million-euro Women's Economic Empowerment and Rural Development Programme, who was among those being removed.

Educational Changes for Women

On Saturday 18th September, the Taliban’s new education minister announced boys ages 6-12 were authorised to return to school, taught by male teachers.

However, there has been no further mention of school girls or female teachers returning. While it had been previously stated that girls would be given equal access to education, the current actions under the Taliban rule suggest otherwise. This ban on women’s education could suggest the beginning of a mass restriction on women’s rights in Afghanistan.

This current ban on female schooling is a violation of the fundamental right to education for girls and women. This perspective was argued by UNESCO’s Director Audrey Azoulay during the opening of the U.N. General Assembly, held in September 2021.

The current actions of the Taliban provide contradictions between promises and actions; further restrictions have been put in place, harkening back to the situation in Afghanistan in the 1990s, where women were refused the right to education and not permitted to leave their homes without a male companion. While the Taliban government suggested that women’s rights were not going to be impacted, the current actions being carried out suggest otherwise.

The closure of the women’s ministry, MOWA, reflects the Taliban’s lack of support in women’s rights and suggests they have no plans to further implement any further women’s rights. Female university students were also informed that their studies, if continued, would take place in gender-segregated settings for the foreseeable future, with further strict Islamic dress code.

History Repeating Itself?

It is important to acknowledge women’s human rights in Afghanistan were in danger long before this current Taliban takeover.

During the 1950/60s, Afghanistan took several steps towards becoming a modernised country. This included approaching a more liberal and westernised lifestyle, in addition to the establishment of girls schools and funding of new universities. Some women were also able to attend college, get a job, and even get into politics.

When the Taliban rule started in 1996, women’s human rights began to disintegrate. During this regime, their strict interpretation of Sharia law, which was sometimes brutally enforced, went against the current progressions that had been made, which included the banning of women attending school, jobs, and public life.

Women were forced to cover their face and were required to be accompanied by a male presence if wanting to leave their home. Those who broke the rules under the Taliban regime faced public humiliation, including public beatings by the Taliban police.

What can we do?

While the events in Afghanistan are not at the same level of extremity as they were in the 1990s, they are still happening.

The restriction of female education and further restrictions of public life imply the past is repeating itself. It is as important as ever that our society ensures that the progress in Afghanistan over the past 20 years is not erased.

While the UN Security Council’s strongly-worded press statement evidenced that the Taliban should uphold the equal rights of women and girls, further pressure needs to be placed on the UN to confirm that these restrictions cannot be allowed to continue.

Ways to help

Women for Afghan Women, WAW, is the largest women’s organisation in Afghanistan that provides life changing services and education for women who have endured rights violations and further advocates for women’s rights to bring about change. They have partnered with Bookblocks to create exclusive artwork inspired by iconic author Louisa May Alcott. All profits from this partnership goes directly to WAW to help Afghan women gain access to education. This campaign, among many others, is a massive support during this dangerous time for women and will help to provide hope for a stronger, better future.

Olivia Fraser is the Women and Children’s Human Rights Editor at Wandering Educators. She is currently studying a Master’s in Human Rights and Diplomacy at the University of Stirling. She is motivated by a desire to emphasise the importance of women’s human rights.