What I couldn’t articulate in my early career track as a teacher was that whenever I observed environments where students of color were present, I noticed the ways that implicit bias may have been at play in their learning and school environments. For instance, bias is obvious to me in school hallways in which children are walking single file, with bubbles in their mouths, to prevent them from talking to each other. This ill-advised classroom management strategy asks kids to close their lips and puff their cheeks, as if they are holding a bubble. These are practices and structures that don’t increase learning, but instead induct primarily students of color into a carceral mindset that their white and affluent peers rarely, if ever, experience. This is both an outgrowth of the white dominant society, and a specific action toward Black children that has its roots in slavery and the systematic control of Black people’s bodies and free movement.

I’ve also seen how bias influences learning content that holds a single view or perspective, without ever considering how it may land on the ears of students from Black, Indigenous, or other communities—those who rarely see themselves reflected in stories, nonfiction topics, or depictions of “influential” figures in science, math, and social studies.

I notice teachers skipping over rigorous questions and activities, only to insert questions or texts that are grade levels below students’ abilities and what they deserve, in part because I understand that bias informs that choice. Because of bias, educators do not question their own intentions in “meeting students” at their assumed level of intelligence and abilities. Our inherent belief about students and what they can do is connected to the shame we inadvertently project onto our students. We may leave unquestioned students’ lack of skill sets of unfinished learning—that is, concepts students have not yet mastered—knowledge they will need to grasp upcoming ideas. In other words, when our own unexamined expectations are low, we may not question a lack of skill sets as anything out of the ordinary.

Teachers can address unfinished learning by re-engaging with concepts their students haven’t grasped within their grade-level expectations, focusing on how to eliminate students’ shame instead of systemizing it through remedial coursework. And yet, bias forecloses this approach in many classrooms and schools.

Bias in Action

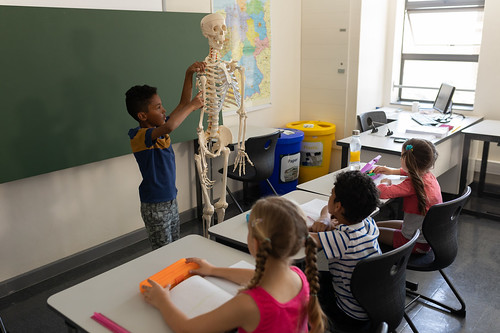

For example, I once witnessed the immediate effects of biased thinking around expectations of learning while walking to a classroom in a well-known charter school, housed in a historic Louisiana building. Inside, I immediately took stock of the school’s predominantly Black student population and overwhelmingly white teaching and leadership staff. I then sat in on a fifth-grade math lesson and walked around the room to peek in on the students working on their assignment: a self-paced computer program that asked them to figure out pictorial addition sums. Any educator could glean that this lesson was meant for a kindergarten or first-grade lesson, not children on their way to middle school.

A young girl with brown skin and beautiful, intricate braids grabbed my arm to stop my progress down the aisle. She pulled me down to whisper, “Can you be our teacher?” As I rose and made eye contact with her, I saw a pleading in her eyes. Looking around the room, I realized that what I initially thought was students’ over-compliance in this silent math classroom, was truly catatonic boredom. I still feel the rock in my throat when I think about that moment, the look in her eyes that showed more than her risk of being called out for not focusing. It was a plea of wanting to be removed from the purgatory of stiflingly low learning expectations and from the presumptions that were most certainly being made in that moment and in many moments to come.

I pulled the teacher aside and asked, “What is the goal of this activity?”

She responded, “Well, these children have severe discipline issues, and many of them only know a miniscule amount of math facts. I can’t possibly teach them fifth-grade content if they can’t add.”

I went back to the school leader to inquire further. “I didn’t realize this was a self-contained classroom.”

She quickly responded with a look of confusion, “It’s not.”

Not wanting her to think I was making assumptions, I responded, “Well the classroom teacher just informed me that the students in this classroom (all 34 of them) had severe disciplinary issues.”

Her response came after a nervous giggle. “Oh, she is new to teaching and has had some struggles with her classroom management. She has received coaching and was told to ensure that she kept the students on task and rewarded them when they have complied.”

I very quickly got to see what the reward was, because the timer went off and the teacher turned on a classroom speaker that blasted the latest hip hop song. Once again, it was clear that unexamined bias fueled these learning practices and would ultimately contribute to patterns of unfinished learning for that young girl and her classmates. Unfortunately, in that role, I never had the opportunity to follow up with that teacher to share my observations and concerns. But when I see classroom practices like this repeated and watch them develop into patterns that impact Black and brown students, I have moments of anguish.

Upholding an Outdated Structure

I would be remiss if I only accounted for times of witnessing educational injustice as an outside observer, without confessing my own participation in supporting and creating similar structures with the children of color I’ve taught or guided as a school leader. Early on in my career, I desperately wanted to succeed as a “good teacher”—so much so that I never questioned the structures or rules of engagement set by my school or our school system.

Like many educators who came of age in the era of education reform of the 1990s through the late 2010s, I focused heavily on aesthetics, giving students the appearance of the structure I assumed they were lacking.

I wanted the students to dress as if they were in a building of high academia: uniforms, ties, and all. But once they sat at their desks, the expectations of high academia were placed on a shelf, except for the students who demonstrated assimilated cultural norms or who read on grade level and beyond. I didn’t push their teachers to distinguish between designing scaffolding strategies that led students toward more complex material, instead of remediating to the point that students did not grow academically. I didn’t push the district to bring in materials that were structured with rigor in mind. I was a cog in the wheel of a machine that was grinding children down—especially Black and brown children—and stripping them of their educational agency, intrapersonal growth, and belief in who they were and what they were capable of.

Oftentimes, years later, I would meet the “fruits of our labor” out in the community: students who had matriculated out of our halls and were adulting as best as they could. My former students sometimes worked at the mall or in restaurants I frequented. I was always elated to see them, all grown up, but I would immediately be met with guilt that their dreams of big careers or expansive lifestyles were less attainable because of the education they received with us. In fact, making it out of poverty was nearly unattainable, in part because my fellow educators and I did not teach young people the foundational skills necessary to thrive or to support their desired life trajectories. The aesthetics we created around discipline and rigor did little to help them to fill out a FAFSA application, enroll in a college, or matriculate into careers that would provide financial security. We had not equipped them to be the kind of students that other students like them needed to see in the future. We had neglected to do all of this, but also I, as a Black woman educator, had unknowingly contributed to solidifying their place in cyclical and systemic poverty.

While I often sensed that something was wrong in our approach, the reasons for this would take years for me to unravel. If we educators want to push our practice into something that is truly worthy of our students, we have to first deeply engage with the historical foundation that we still uphold today in our school systems. Why? Because the type of K–12 education many students of color receive today—an education that places limits on their aspirations—is inextricably linked with how education for Black and brown students has developed historically in America, and how that development shapes the lenses and layers we bring to our work.

Lacey Robinson is the President and Chief Executive Officer of UnboundEd, a role that accelerates her life’s work to help educators in school systems disrupt bias and systemic racism and its legacies in classrooms. Robinson sets the organization’s vision for equity-driven national change. While continually monitoring the design, delivery, and quality of UnboundEd’s national K-12 educator professional learning programs, Robinson concurrently maintains the nonprofit’s health, sustainability, and future-driven vision for what teaching and learning can be in the 21st century.

She is the author of the new book, Justice Seekers: Pursuing Equity in the Details of Teaching and Learning

In Justice Seekers (July 6, 2023, Wiley), celebrated social justice activist and veteran educator Lacey Robinson delivers an engaging combination of storytelling and research that explains why justice is happening―or not happening―inside the classroom and within the details of teaching and learning. You’ll read insights about how all students deserve a learning environment that is grade-level, engaging, affirming, and meaningful. All students flourish when their education not only acknowledges their identities but the identities of others, affirming who they are as academics and as human beings. You’ll see how adopting this mindset begins our journey toward justice as educators. In the book, you’ll discover the many ways that justice is found in the details of race, pedagogy, and standards-driven education, as well as:

* Strategies for challenging educators to see the ways in which they can contribute to eradicating racial inequity from the classroom and from society

* Ways to recognize and reduce the impact of low cognitive demand material presented to Black and brown children in schools across America

* Methods for improving the quality of your own teaching here and now

An intuitive and exciting roadmap for K-12 teachers, teachers-in-training, school administrators, and principals who aim to reverse the racial injustices today’s children face every day, Justice Seekers also belongs in the hands of educators, parents, and everyone who cares about educational equity.

Connect with Lacey Robinson:

Official site: www.unbounded.org | Facebook: @unboundedu | Instagram: @unboundedu

YouTube: @unboundedu | Twitter: @unboundedu

UnboundEd is dedicated to empowering teachers, instructional coaches, and leaders to meet the challenges set by higher standards, unfinished instruction, and institutional racism by providing resources and equity-based professional development grounded in instruction. Additionally, their learning experiences support state agencies, educational service providers, and post-secondary and teacher prep programs.