Kelmscott Manor: Trouble in Paradise

A story of troubled times at Kelmscott Manor, the country retreat of William Morris...

The most romantic way to arrive at Kelmscott Manor is by river, but even travelling by road you get a powerful sense of its remoteness. And when you walk down the narrow path towards the old grey farmhouse, you may feel, as William Morris did, that you have entered an enchanted place.

River Thames below Kelmscott Looking upstream on the bend below Kelmscott Manor.Wikimedia Commons: Pierre Terre

When Morris first discovered Kelmscott Manor, in the spring of 1871, it was love at first sight. The next day he wrote to a friend describing the house as ‘a heaven on earth’. For Morris and his followers the ‘old grey house by the river’ was to become a symbol of an ideal way of life, and the perfect embodiment of the principles of the Arts and Crafts movement.

Kelmscott Manor. Wikimedia Commons: Boerkevitz

But in 1871, Morris had more personal reasons for seeking out a country retreat…

William, Janey – and Rossetti

Morris was 37 years old when he discovered Kelmscott. A successful poet and designer, he was also a family man with a beautiful wife and two lively daughters, aged ten and nine. The family lived in Bloomsbury, above the premises of Morris and Company (generally known as ‘the Firm’) but all was not well at home. While William worked around the clock, his friend and fellow artist, Dante Gabriel Rossetti (a leading member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood) pursued his wife, Janey, with a dangerous intensity.

Jane Morris (The Blue Silk Dress). Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1868. The Walker Art Gallery (National Museums Liverpool).

By 1871, it was public knowledge that Janey and Rossetti were conducting a love affair. Faced with such an awkward and painful situation (Rossetti was a key member of the Firm as well as a trusted friend), William made a remarkable decision. He would find a house hidden away in the country where the lovers could go to be alone. When Morris proposed to Rossetti that he should share the lease on Kelmscott Manor, Rossetti willingly agreed, calling the house an ‘earthly paradise’. Meanwhile, Morris busied himself with preparing for a long-planned expedition to Iceland. In June, he paid a last visit to Kelmscott before leaving England and wrote a wistful letter to his wife, wishing her health and happiness in their beautiful country home.

Kelmscott Manor depicted in the frontispiece to the 1893 Kelmscott Press edition of William Morris's News from Nowhere. Wikimedia Commons

A serpent in paradise

For three months, Janey, Jenny, and May shared their ‘earthly paradise’ with Rossetti. He took over the Tapestry Room, filling it with his painting equipment, and Janey and the girls were often in demand as his models. In his cheerful moods, Rossetti was a lively companion for Jenny and May, indulging in wild games of hide-and-seek, but they still regarded him with some alarm. He was addicted to chloral, a liquid form of opium, and was prone to sudden moods of black despair. When William arrived at Kelmscott in September, riding a stocky Icelandic pony, his daughters were relieved and delighted to see him, but the summer was over and the house was soon shut up for the winter.

Rossetti returned to Kelmscott the following year, although by then he was in the grip of a severe depression, sleeping most of the day and pacing the house by night. Even after winter arrived, he stayed on at Kelmscott, with Janey and her daughters often in residence. Over the next 18 months, Rossetti treated Kelmscott as his home while Morris stayed away. Several noisy dogs and a pet barn owl were given the run of the house, and a procession of friends and relatives came to stay, including – according to May – some rather racy models who posed in the nude.

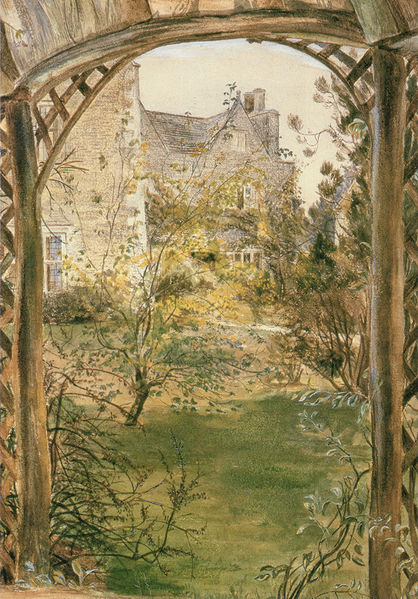

Kelmscott Manor, by May Morris. Wikimedia Commons: Scanned from Pamela Todd, Pre-Raphaelites at Home, Watson-Guptill, 2001

Paradise regained

In April 1874, Morris could bear it no longer. He wrote an angry letter proposing that Rossetti should take on the lease of Kelmscott on his own. It was a desperate gamble, as Morris risked losing the house entirely, but it paid off. Rossetti was unable to raise sufficient funds, and in July he left Kelmscott for good. In the summer of 1874, three years after he had first discovered Kelmscott, William Morris regained his paradise, and for the rest of his life it provided him with inspiration and contentment.

William Morris detail, Kelmscott Manor. Flickr cc: Rictor Norton & David Allen

Today, there are still reminders of turbulent times at Kelmscott. Some exotic pieces of furniture – imported by Rossetti from his Chelsea studio – strike a surprising note in the Arts and Crafts interiors, and a tangle of paint tubes in the Tapestry Room remains just as it was when the artist fled.

Rossetti’s spirit is also present in his art. Displayed throughout the house are his paintings and drawings of Janey and the girls. Yet these are strikingly peaceful – studies of dreamy, fairytale beauties in a paradise on earth.

Water Willow, an 1871 portrait of Jane Morris in the landscape near Kelmscott Manor which appears in the left background. Oil on canvas glued to wood. Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Wikimedia Commons

Jane Bingham, author of The Cotswolds: A Cultural History (Signal Books and Oxford University Press, 2009) and a prolific writer of history books for young people, also writes on English heritage in the national and local press. Jane gives tours and talks on the Cotswolds and has served twice as a Royal Literary Fund Fellow at Oxford Brookes University. Jane leads the Arts and Crafts Guided Tour at Cotswold Walks. At the heart of the tour is a visit to Kelmscott Manor, country home of William Morris, and the ‘Earthly paradise’ that provided the inspiration for so many of his designs.