Zaatar Days, Henna Nights

"Here's a recipe for adventure:

* 5 Mideast countries

* 1 Seattle dotcommer

* A one-way plane ticket

* Several Lonely Planet guides

* Pakistani rosary beads

Mix together with questions about identity and roots.

Season liberally with wanderlust.

Add a dash of faith.

Whip up some humor."

A moment of Peace - Ummayad Mosque, Damascus

I've recently read a book that has had a tremendous impact on how I view the Middle East. Always tolerant and eager to learn about other cultures, I was still unfamiliar with this region of the world or contemporary Arab culture. Then, I read Zaatar Days, Henna Nights: Adventures, Dreams, and Destinations Across the Middle East, by Maliha Masood. At once a memoir about traveling in the Middle East, and a story of intercultural adaptation, learning a new culture, and finding friends - and yourself - this book is an eminently readable journey. Maliha walks in the footsteps of Rumi, is questioned as a spy, visits a Turkish bath, and learns about different cultures and people. Through it all, the friendships that she makes, and experiences that she shares, make a deep impression on the reader.

I read many travel memoirs for Wandering Educators, and enjoy each person's journey. However, Zaatar Days, Henna Nights touches a chord in me - that of learning about yourself, while in a different culture and place, isn't always easy. It can be a struggle, and it can also be full of joy. Maliha writes so well of getting to know places and people that you feel that you're traveling right along with her. She explores culture, religion, friendships, and identity - and shares her cogent observations with us in this treasure of a book. Each page highlights something new - a twist of phrase, a glimpse into another culture - that keeps you reading long after your bedtime!

"Allah can turn your world upside down in the blink of an eye," my mother always said. Whenever I made grandiose plans or built those castles in the air, she chastised me for forgetting to bracket my dreams with the requisite Inshallah, or God Willing. It was her way of reminding me that controlling life was an illusion, and I often argued back that in spite of this illusion, we have to go along with the preence of control so that we don't just sit there and do nothing. But no one is telling you to sit and twiddle your thumbs, was mom's rationale. She added that it was imperative to exert an effort, to act, to struggle, as long as one had agency in faith. There is a phrase for this in Urdo. Khudi k tayari. It roughly translates as preparing one's self.

For a long time, I had never really understood what this preparation was for. Now I wondered if the goal was to reach an ideal state of self-knowledge, which of course is a lifetime's work. But I had made some headway by having found a truer mirror with which to see and feel myself..."

We were lucky enough to sit down and talk with Maliha about her book, intercultural adjustment, friendships, and traveling as a Muslim. Here's what she had to say...

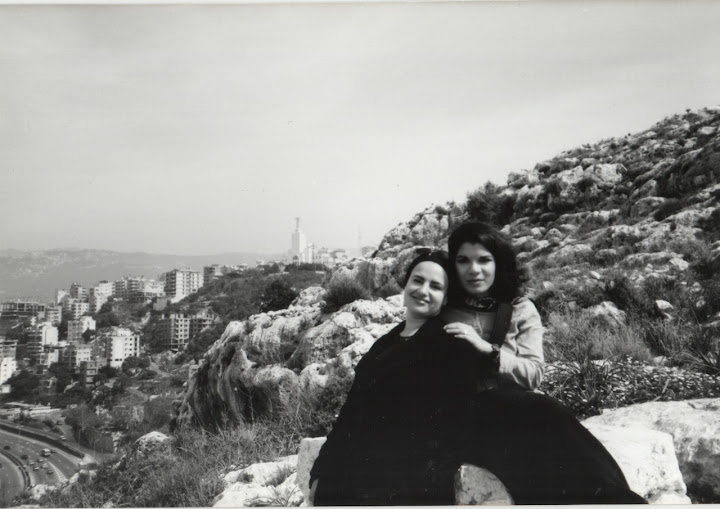

Basking in Beirut, Bea and I

WE: Please tell us about your book, Zaatar Days, Henna Nights...

MM: It's a travel memoir about my experiences backpacking in the Middle East just before 9/11. It was a solo year long overland journey through Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria and Turkey. I went to the Mideast as an escape from my life in Seattle, where I was burned out from work in the IT sector, basically just bored and unfulfilled. As I write in the book, I wanted to know what else I was capable of beyond the bullet points of my resume. I was essentially in need of some soul searching. And I became convinced that I had to do this soul search by charting off to see the world with no game plan and return date. So I quit my job and left behind my family with a one way ticket to Paris. 6 months of traveling around Europe was not enough of a break. I was looking for a real challenge, a way to push my limits, and I realized that my journey had to involve adversity and danger in order to make me grow. So I headed off to Cairo. I had no idea what I was going to do there, did not speak a word of Arabic, but I was dead sure that I was doing the right thing. There were two reasons why I was drawn to the Middle East. One was pure wanderlust. The other was a desire to connect to my Islamic roots. I consider my book a cross between Walt Whitman's call of the open road and a hadith or a saying of the Prophet Muhammad to travel for the sake of self knowledge. My book is both an internal journey as well as the external journey of the people and cultures that I encountered in the Mideast. It's about hearts and minds and how we go about learning about ourselves through the lens of strangers in strange lands.

Hanging out with Beit Jabri Damascus

WE: What led you to write this book?

MM: First of all, I had no idea that I was going to end up writing about my travels in the Mideast and turn it into a book. I did not start out with that intention. The impulse to write about the journey was because of the events of September 11, which happened just 10 days after I returned to the United States. It was a quite a shock. Here I was back home after a year and a half on the road, the most intense, rewarding, life affirming experience of my life. The Middle East was my love affair, not my terror den. But a very different perception about the region and Muslims emerged on TV and the news in the wake of September 11. That's when I knew I had to write about my journey in order to shed more light, more perspective. It wasn't about sugar coating terrorism and the violence in the Muslim world. But I wanted to show an American audience that there is more to the Mideast and Islam than negativity. The need to humanize the region and focus on common ground rather than differences became very important to me. I also wanted to honor the courage and will power that enabled me to travel like a nomad with no advanced planning or road map. It was the only time in my life when my heart and my head were speaking the same language and I wanted to remember that feeling of being utterly in the moment and alive which is what happens when you surrender to the journey.

In many ways, writing about the journey was a journey in itself. I was having to deal with two very different realities. One was the reality of all the fun and adventures I experienced in the Mideast. The other was the post 9/11 reality of all the fear and suspicion surrounding the Mideast and. Muslim world. I had to reconcile both realities and I wrote the book to show people that there are always two sides, two ways of looking at something. So much of my book is the voices and images of the people I met in Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Turkey. They challenge so many stereotypes about the culture and society. At first it was hard to capture it all in writing since I took no notes and had no recorded information other than my photographs. So the book relies entirely on my memory. I'm a visual thinker and writer and much of the book reads as if you're in a movie seeing the sights and meeting the folks, in this virtual reality form of travel which is why I joke about Zaatar Days, Henna Nights being the cheapest way of going to the Mideast from the comfort of your living room!

Young Carpet Weaver, Turkey

WE: Intercultural adjustment is something that is rarely mentioned in travel memoirs, yet is critical for truly living - and being - in a culture. Can you share your strategies for intercultural adjustment?

MM: I think it's all about attitude. You have to be open to learning new customs, new ways of thinking even if they clash with your personal beliefs. Much of my adjustment had to do with trusting strangers, accepting their advice, suggestions and hospitality which is really big in Muslim culture. I think it helps to have a routine and I would make a point of having breakfast in the same cafe every day, going to same fruit vendors for my shopping, visiting the same mosque on Friday prayers. It gives the traveler a sense of continuity in an ever changing landscape. More importantly, it makes you a familiar face so people get to know your name and begin to open up to you and see you not just as a tourist. I also made it a point of living in the major Mideast capitols for at least a month or more to give myself a home base. You can easily do this in cheap backpacking hotels which is how I lived for over 3 months in Damascus. I also left a great deal to spontaneity and chance encounters which can be either good or bad. Luck has a lot to do with it. I learned that trusting others is ultimately about trusting yourself. You have to have that inner confidence in order to let go of the self and learn new things without fear.

WE: New friendships, while living abroad, can be very important. You certainly found some incredible friends. How did these friendships change how you felt about yourself and your travels?

MM: I realized that my friendships were more than just random encounters that made me less lonely on the road. My friends in the Mideast were my cultural windows into a world that was no longer riddled in abstractions or fear. It was a world that I was getting to see upclose, I call this sensory knowledge and it gives you a far more intimate glimpse into a culture than a scholar who has read a ton of books about a place or the policy pundits who debate Muslim world politics without taking the trouble to travel in the region. My friends were also the necessary prism through which I saw myself reflected. It made me appreciate all that I had left behind at home and I realized how incredibly lucky and privileged I was to travel and be self reliant. In fact, most all my book is about these friendships and how they turned around stereotypes and were sources of cultural enrichment and so much joy.

The rooftop conspiracy, Aleppo

WE: What was the biggest surprise about your journey?

MM: I went on this journey as a personal quest. In many ways, I had no control over it. I felt as though I were following a set of instructions and I was dead sure I was doing the right thing at the right time. Having said that, I also knew the journey was going to be the biggest challenge of my life. And what surprised me the most is the way I took to it, almost relishing the difficulties because they made me push my boundaries and get to know all these hidden strengths and capabilities. I think that's what so invigorating about adventure travel, it's like taking an exam that you can't possibly prepare for. And in the Mideast, I constantly came up against issues that tested my limits and each time I pushed them, I broke through a barrier, that was emotional, mental and spiritual. The ultimate surprise was how similar people are all over the world, despite all our differences, we yearn for the same basic things like love and friendship and that can be very powerful in bridging cultural gaps.

WE: What was your favorite country and why?

MM: By far, I most enjoyed Syria. It was a fascinating combination of the old and the new, traditional and modern and having grown up as a hybrid between east and west, it felt so natural to me to pray in a 13th century mosque in the afternoon and the same evening go salsa dancing in a nightclub. You can do that in Damascus, Aleppo. And you also get to dine on fabulous food in fancy restaurants and pay McDonald prices. It's so affordable to live there and going to historic old souqs or having coffee overlooking a medieval fortress were everyday occurrences. You can get spoiled with that kind of stuff but it makes a nice change from the corner Starbucks and strip malls back in the States.

Murad as Dervish, Aleppo

WE: Was it easier traveling in the Mideast as a Muslim?

MM: Yes and no. As a Muslim, American and a woman, I found myself walking a tightrope at all times. It was hard for people to accept me as a package of all three identities. They either saw me as a Muslim which meant I couldn't just roam around by myself, befriending strangers in the street, which I did anyhow, but then I was immediately pegged as a foreigner, and the fact that I wasn't fluent in spoken Arabic made it much harder to be fully accepted. I realized that being a Muslim wasn't enough, particulary in the Arab world, where language takes precedence over religion in terms of fitting in. And I found it a double standard in many ways, being a Muslim from South Asia, having grown up in the States, and yet, being treated as an outsider, someone who didn't quite belong, but everytime I walked into a mosque, or heard the call to prayer or saw a sign in Arabic, I did feel so grounded there. It was a sense of belonging, cultural more than a sense of home or roots, and it was hard to explain to people that I wasn't just a stranger. I was constantly having to negotiate the feeling of being an outsider and insider at the same time. And as soon as I started wearing the headscarf, I blended in with the locals, which meant I couldn't get away with allowances for tourist mistakes, such as not knowing the subway rules in Cairo. It landed me in some trouble, this case of mistaken identity and ever since then, I was torn between my desire to fit in and not stand out and just being this naive wide eyed traveler discovering these places for the first time. A very odd situation to be in, this sense of belonging and not quite belonging.

WE: What's up next for you - with travels, and writing?

MM: Actually, I'm pretty busy now being a new mom. So I'm traveling in a whole new way in my own backyard. I'm also working on another memoir about Pakistan where I was born and raised. I traveled there after the Mideast in 2003. It was my first trip back home after 21 years. I saw a lot of changes. And I think it's important to show a different side of Pakistan, other than just violence. As a traveler, I had a knack for finding adventure at every corner. Pakistan was certainly no exception. I'm still working on the manuscript but I have some travel journal entries from Pakistan on my blog, which I've called Blogistan.

WE: Thanks so much, Maliha! I highly recommend your book and urge our Wandering Educators to read it, as well. It is an excellent memoir, delving into so many critical issues of global (and personal) understanding.

All photos courtesy and copyright of Maliha Masood

-

- Log in to post comments