Haiti's grim reminder to Nepal

On the morning of Saturday, April 25, 2015, a massive earthquake struck central Nepal between Kathmandu and Pokhara. Currently estimated at 7.8 or 7.9 on the Richter scale, the magnitude of this quake is about sixteen times as great as the one that wrecked Haiti on January 12, 2010. Information so far is sketchy, but the confirmed death toll in the Kathmandu area is over 1100; that figure is certain to rise much higher. Aftershocks rolled through Kathmandu all day, and as night fell, it was raining and chilly, but few people dared to sleep indoors.

The Red Cross and many other aid organizations are urgently requesting your help. Sunrise Pashmina would suggest donating to The Mountain Fund, a grass-roots NGO with numerous projects in central Nepal, including hospitals and clinics in Rasuwa, at the epicenter of today's event. Scott MacLennan, founder and director of TMF, was awarded the Sir Edmund Hillary Mountain Legacy Medal in 2010. See our article http://www.wanderingeducators.com/best/stories/i-do-it-because-i-can.html

The article below, posted by WE in the wake of Haiti's disaster, explains why Nepal was due for an earthquake, and some of the factors compound the risks of long-term disruption in Nepal.

****

The recent earthquake in Haiti, and the ongoing disaster that ensued from it, have given us all a lot to ponder. I've been thinking about the two earthquakes I experienced, both in Kathmandu.

The first was in 1975, I think. I tried to google it, but it was relatively minor (5.6 on the Richter scale, if I remember correctly). I was living in Century Lodge on Freak Street, where I had spent several months already in a 6' x 9' room. Eight rupees per night, at a time when the rupee was about 10 or 11 to the dollar. I had no furniture, just a built-in shelf that served as bed and table. There was no heating, and the only light bulb was 40 watts; Suman said that the wiring (which he had installed himself) couldn't handle any more.

I was hunched in my $12 Sears Roebuck sleeping bag, grading papers by that miserable light, when things got weird. I taught at the English Language Institute on New Road, and had a couple dozen books piled on my bed shelf, but they all jiggled over to the edge and onto the floor. Then my light went out. I got up and walked across the hall to the little terrace. My room was on the fifth floor, higher than most other buildings in the neighborhood, so I had a view across the rooftops. There must have been a moon, because I could see pretty well despite the blackout.

Believe it or not, it took me another minute or so to figure out that I was in the middle of an earthquake. A Californian would have known immediately, but for an East-Coastener, earthquakes are about as exotic as animal sacrifice (also uncomfortably common in Kathmandu). I began to get the point when I noticed that the top of our building was swaying back and forth about three or four feet in each direction. There was a muffled roar in the air, and dogs were yapping frantically. People were yelling nearby and when they stopped for a moment, I could hear more voices far away.

Despite the noise, nothing much was happening that I could see, and it didn't seem like a good idea to rush down into the narrow streets below. If buildings started to collapse, I liked my chances on top of the pile rather than down there. So I just stayed put and enjoyed the novelty.

As I walked to work that morning, I spotted some new cracks in the sidewalks and a few damaged facades, but nothing dramatic. Within a couple of weeks we would learn there had been several dozen deaths in the eastern hills, closer to the epicenter, mostly due to landslides, but such news traveled slowly in Nepal. One thing did surpise me. BBC was reporting that the earthquake had lasted only around twenty seconds. "That's ridiculous!" I said to Manesh Agrawal, the ELI secretary. "I heard it and felt it for at least five minutes, and probably more than ten."

"No, Seth-ji," Manesh answered. "You felt shaking because Kathmandu Valley is an old lake bed. The sediment shakes like jelly in an earthquake, even after the earthquake stops."

Manesh also pointed out that if the quake had occurred during the morning or evening, when people were cooking, the Old Town with its wooden houses and temples would have burned to the ground. In fact, given the lack of fire departments and water pressure, the whole city could have burned.

My next earthquake was on August 21, 1988. I was living on the outskirts of town, in a house surrounded by rice paddies. In the middle of the night, Namche, my Irish Wolfhound, came to my bed and woke me. I shushed her and went back to sleep. A few minutes later she was back, with a non-negotiable paw in my face. As I got up and opened the door for her, I saw that the hanging spider plant was swinging back and forth. I touched my head, wondering if I had bumped into it, until I saw that all the other potted plants were also whipping around. Namche balked at the door, and then I heard that same roar in the air and dogs barking across the valley. More chilling was the cumulative siren of grown men screaming. I tried to think what to do -- I'd heard you should stand in a doorway, so I did that briefly, before realizing that the safest thing was simply to step away from the house.

Seth and Namch. Nepal's dramatic scenery comes at a price.

Again, there was little damage in Kathmandu, but to the east the impact was not so neglible. As my dog had noticed, there were two shocks (10 and 15 seconds), 6.6 Richter; they left 722 dead in Nepal (plus another 282 in India), and thousands injured and homeless. The total cost to Nepal was estimated at one-fourth of Nepal's Gross Domestic Product.

As disasters go, earthquakes are relatively survivable. Unlike tornadoes, hurricanes, tsunamis, avalanches and floods, you can be right in the middle of a mild one and hardly notice it. Even if you're in the middle of a huge one, you may be totally unscathed -- as long as you're not in a position for anything to fall on top of you. Small and medium-size earthquakes may cause deaths, but they're often out of sight -- in remote mountainous areas, where entire communities may be wiped out, leaving the urban centers nervous but whole.

And then there is Port-au-Prince. When the nation's capital is destroyed, no one is left whole, no matter where they were standing when the shaking began. The spectacle of a nation brought to its knees has, at least for a while, riveted the attention of Nepal's government, media, and people on the street. No surprise, either: this is not a case of "there but for the grace of the gods go I." Everybody knows that it will happen, and it will be worse.

Pumori (shot from Kala Pattar in the Everest cirque)

The Indian tectonic plate that arrived on the shores of Tibet some 70 million years ago is still driving forward, moving at 45 mm per year. Some of that pressure is absorbed by upward thrusting and subduction, resulting in an average annual lift of about 5mm all along the Himalayan arc. The movement isn't smooth, however. Most of the energy is being stored up in compressed rock, coiled, waiting for the next release. Seismologists say that six meters of slip is sufficient for a Great Earthquake. Western Nepal is sitting on about nine meters of impacted slip, ready to go. Since 1255 AD, the region has been subject to huge quakes every 75 years or so. The latest was in 1934. You can do the math.

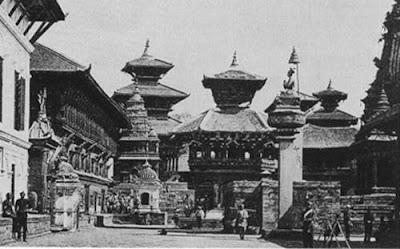

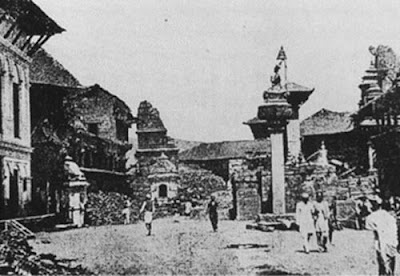

Bhaktapur's Durbar Square, before and after the 1934 earthquake

How could a quake be worse than what's happened to Haiti?

First of all, there's that lake bed that underlies the entire Kathmandu Valley. Much of it is hardly more compacted than the soil in your back yard. After the plate lurches forward, the ground will shake like jello for many minutes. The natural frequency of the silt tends to resonate with shallow quakes and amplify the waves, an effect observed in the 1985 quake that struck Mexico City.

And, as in Mexico, that silt is subject to liquefaction (behaving exactly like quicksand) under the pressure of seismic waves, resulting in the destabilization of any infrastructure resting on it.

Secondly, because of the more accidented landscape, there are likely to be cascades of disastrous events. Much attention has been focused recently on the growth of lakes as glaciers retreat. Held back by moraines (generally unconsolidated and frequently ice-cored), these lakes become progressively more unstable as seepage erodes the retaining banks and the cementing ice cores melt away. In 1985, a small Glacial Lake Outburst Flood (GLOF) from Dig Tsho (a few miles upstream from Namche Bazar), was triggered by a chunk of overhanging glacier that splashed into the lake and caused an overtopping wave. A new hydroelectric plant was wiped out, as were all the bridges and quite a few homes for dozens of miles downstream.

A large earthquake will cause avalanches to plunge into Tsho Rolpa (in Rolwaling) and Imja Lake (in the Khumbu), as well as other glacier lakes, causing some to breach. The resulting floods will wipe out most infrastructure along the river courses through Nepal and into India, making rescue and recovery efforts very difficult.

Even without the glacial lakes, there will be numerous landslides damming up narrow gorges, resulting in new lakes that will break out sooner or later as GLOF-type events.

If the earthquake hits during the monsoon, when the land is waterlogged, landslides will be significant hazards in themselves. In the winter, when precipitation is very infrequent in the lower valleys, there is a danger of fire. With or without fire, the inversion effect of the bowl-shaped valley (which makes pollution such a problem already) will trap the dust and smoke, possibly for weeks.

The design of the city is itself a problem. Most of the streets are narrow. Building codes were nonexistent until very recently, and are still not being enforced. Retro-fitting is unlikely to be applied on an appropriate scale. Most of the bridges are unsafe. Standards for storage of kerosene and gasoline are essentially nonexistent.

The rescue and recovery phase will be a nightmare. Rajanis Ojha, Senior Disaster Risk Reduction Project Coordinator for Red Cross Nepal says that Kathmandu will be at greater risk than the rest of the country. "Due to the haphazard settlement," Ojha told Xinhua, the Chinese news agency, "there is no way ... to rescue people [in the] aftermath. People here will die more not because of the seismic activity, rather they will die more for not getting rescue facility." Ojha predicts that more than 100,000 people will die in Kathmandu simply because the city is so poorly run.

Ojha is right. Waste treatment is virtually non-existent, water distribution is dysfunctional, electrical wires are massed in tangles above the streets. For a city of 1.5 million, there are only a handful of firetrucks, and they will be useless -- probably stuck in their garages behind jammed doors. I've never seen an ambulance in Nepal. Hospitals are few and poorly staffed and equipped.

Unlike Haiti, Nepal will not be able to expect immediate help from abroad. Landlocked, it has no ports. The single-runway airport will certainly be knocked out. The three major roads into Kathmandu, scary under the best of circumstances, will be unpassable. India will be digging out from its own share of the disaster, as will China.

Disease will probably take as many victims as quake injuries. Cholera and various forms of dysentery are endemic, and with sewage leaking into the water supply, and no fuel to spare for boiling water much less washing up, epidemic is inevitable.

So what is to be done?

It seems to me that there are two general perspectives on this kind of risk. From the Nepali point of view, there is no way to substantially mitigate the concatenated dangers without becoming a developed nation. Even then, as the 1995 Kobe (Japan) earthquake showed, it's hard to cover all your bases. At least the Nepalese government has started programs to retrofit schools and educate children about how to maximize chances of survival of the initial shock, and there is talk about enforcing building codes. It will probably be too little, too late.

From the visitor's perspective, risk assessment is always an irrational process. During the past few years, tourism fell off drastically in Nepal due to the Maoist revolution. Although it is true that there were atrocities committed on both sides of the war, there were virtually no tourist casualties. And yet many tourists perceived the risk as unacceptable.

When it comes to natural disasters, on the other hand, most people tend to disregard those risks entirely. But let's just choose some numbers. If we accept that another Big One will strike Kathmandu within twenty years, then for every day you spend in Nepal you have a 1-in-7300 chance of being there at the wrong time. If you stay for ten days, which is probably less than the average for most Western tourists, that gives you a 1-in-730 chance of being there. If lotteries operated with that kind of odds, a lot more people would be buying tickets. If one in 730 airplane flights crashed (or one in 730 passengers died, which is the same thing), there would be fewer frequent fliers.

And yet, I am not suggesting people avoid Nepal, nor that Los Angelenos come back to New York. I'm just saying that tourists ought to have given earthquake survival a little more thought than, for instance, the average East Coastener just off the plane. If you're staying in Kathmandu, you might want to stay in an all-wood guest house rather than a great big hotel with dried sand instead of mortar. If you're with a group, choose a safe place to meet when the dust settles -- such as the far southeastern corner of Tundikhel, the parade ground at the center of Kathmandu. If you're hiking along a river and the earth starts shaking, head for higher ground as quickly as possible. And, if you're in a village that wasn't completely trashed, maybe you'll want to stay put for a while; you can pretty well guess that Kathmandu will be hell on earth.

After all, you've had the advantage of witnessing Haiti.

Kala Bhairava, the annihilator. This 12-foot high statue of Shiva in his the fiercest aspect is a favorite of locals and tourists alike. Theoretically, the corpse he is trampling represents ignorance. Let's hope!

Feature photo: Despite mitigation efforts, Nepal's notorious Tsho Rolpa is a lethal Glacial Lake Outburst Flood hazard

Seth Sicroff, Nepal Editor for Wandering Educators

Manager, Sunrise Pashmina

All photos (except the two stock photos of Baktaphur) courtesy and copyright of Seth Sicroff

-

- Log in to post comments