Lost Railways from Around the World: Listowel & Ballybunion Railway

Submitted by Dr. Jessie Voigts on Tue, 12/04/2018 - 22:24

Note: This is an excerpt from a fantastic new book by Anthony Lambert, called Lost Railways from Around the World. We love it so!

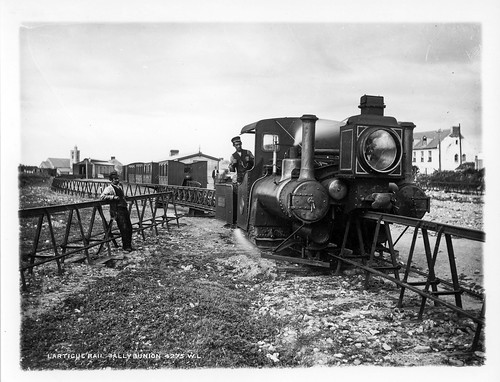

In a country blessed with more than its fair share of idiosyncratic railways, Ireland’s Listowel & Ballybunion Railway (LBR) in County Kerry won the laurels. The best-known of 19th-century monorails has spawned many stories mocking its impracticality, but it was one of the most visited and photographed of Irish railways because of its demonstration of Charles Lartigue’s monorail principles.

Though called a monorail, Lartigue’s system used three rails: a raised centre running rail mounted on A-framed trestles, and two mid-trestle rails to prevent oscillation. Its virtue was claimed to be cheapness of construction, since liberties could be taken in preparing the trackbed. Its drawbacks were added complexity in the mechanism required to switch tracks, the awkwardness of having locomotives, carriages and wagons that straddled the centre running rail, and the conundrum of how to cross a road.

The 9¼-mile (14.8km) line was authorized in 1886 and officially opened on Leap Year Day in 1888, though most of that time was spent acquiring the land; construction took just five months. The line linked the County Kerry seaside resort of Ballybunion with Listowel station on the Great Western & Southern Railway Tralee–Limerick line. There was a single intermediate station with a loop and siding at Lisselton. Ballybunion station was equipped with a goods shed and sidings, and the line continued for a short distance past the church to the shore for loading sand.

The girl might well look at the idiosyncratic locomotive waiting to leave Listowel station, for there was nothing else like it in the British Isles. It ran with ‘a happy disregard for punctuality’. Photo: Archive Farms Inc / Alamy Stock Photo

Three dark green-liveried locomotives, based on a design by the French mechanical engineer Anatole Mallet, were built by Hunslet of Leeds. Two locomotives were housed at the Ballybunion headquarters and the third at Listowel for the first train out in the morning. The driver was on one side of the running rail, and the fireman on the other.

The only months when the railway made a profit were during the summer – when the population of the seaside resort of Ballybunion swelled from 300 to 3,000, thanks to the excellent bathing. Apart from the carriage of general merchandise, the L&B brought sea sand inland for use as top dressing. Though the railway had a horse box and two cattle trucks, livestock traffic seems to have been negligible, perhaps because farmers considered the distance between Ballybunion and Listowel to be so modest that it was not worth the expense of getting the railway to take their beasts to market. More telling might be the logistical difficulty of moving one animal, which naturally required a balancing load.

The story is told of the tribulations of conveying a piano; this entailed borrowing two calves to provide the means of a balanced return working. Another tale, perhaps apocryphal, is related by Fergus Mulligan: a farmer ‘bought a cow at Listowel and borrowed another for the train trip to Ballybunion. A second animal was then needed to return the first one borrowed and so the business went on for most of that day until he had lost his own cow, acquired two he did not want and owed the company a small fortune in freight charges.’

Ballybunion station in 1890 with the engine shed above the man leaning against the A-framed trestle. Photo: Michael Whitehouse Collection

The three locomotives were painted dark green. The tenders had an additional pair of cylinders but they were apparently not used. Photo: Michael Whitehouse Collection

Road crossings entailed a rotating section of track or a canal-pattern double drawbridge operated by chains and pulleys, of a complexity that would have delighted W. Heath Robinson. There were 40 crossings of one sort or another on the line, and a silent 9.5mm Pathé film survives showing a donkey and cart negotiating one. Steps were provided at the end of some of the carriages so that passengers could cross the line.

A visitor in 1917 was not impressed by the view from the carriage window: ‘there is nothing to be seen beyond peat land and scrub’; and The Engineer reported that the line passed ‘through deep bogs and bad ground generally’. Nor did passengers take kindly to the noise generated by the rail behind their heads, seating being back-to-back. By 1897 the line was bankrupt and placed in the hands of a receiver, but it struggled on through the next two decades. During the Civil War, there were various acts of sabotage, and the frequency of mail robberies prompted the suspension of services for a period. The last straw came in 1924 when it was not included in the creation of Great Southern Railways, making closure inevitable. The last train ran on 14 October, and the line was dismantled with great thoroughness by T. W. Ward of Sheffield.

A suggestion was even made in the London Evening News that an engine from the railway should be preserved in the Victoria and Albert Museum to illustrate engineering progress. Nothing came of it, but in 2003, a 2⁄3 mile (1km) section of Lartigue monorail was opened on the trackbed of the line in Listowel. It is worked by a diesel-engined replica of one of the original locomotives built by Alan Keef.

Locomotive No. 1 soon after arrival on the railway to judge from its numberplate on the tender – they were soon transferred to the cab sides. The two boilers were designed to use coal but an experiment was made with peat in 1917. Photo: Michael Whitehouse Collection

The steps at the end of a carriage to allow the line to be crossed being demonstrated at Ballybunion station with the castle ruins on the right. Photo: Wikimedia/Creative Commons/ Oliver Wald

The L&B attracted many visitors for its curiosity value, as here at Ballybunion station. Photo: Michael Whitehouse Collection

/div>

Photos and excerpt used with permission (thank you!).

-

- Log in to post comments