Climate Change and Inequality: Does Climate Change Discriminate?

Does Climate Change Discriminate?

People who are at the highest risk from the effects of climate change are those who already face global inequalities. Currently, climate change does discriminate against vulnerable groups. This includes people in developing countries, people of colour, ethnic minorities, and women. i

Vulnerability in the climate crisis can be defined by insufficient resources, funds, and overall ability to respond to the effects of climate change. ii Unequal access to these requirements allow climate change to create global injustices.

What is Climate Justice?

Climate justice is a movement that not only understands the disproportionate effects of the climate crisis on human life, but fights to change it. By placing human rights at the forefront of its efforts, climate justice gives a voice to the voiceless.

The climate justice movement wants to achieve global equality by arguing for climate policies that support those who are most vulnerable in the climate crisis. iii

Whether you are rich or poor, or minority or a majority, we all have a responsibility to stop climate change. And in our efforts, we must protect those who face the worst consequences of our collective actions.

This piece will look at three of these vulnerable populations who need climate justice.

Developing Countries

This piece will refer to developing countries as countries that are less advanced socially and economically. Populations within developing countries face far-reaching problems such as poverty, hunger, lack of/ no access to clean water and sanitation, and so much more. In 2000, the world leaders’ introduced the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). This set out 8 goals that aimed to narrow the gap between developing countries and developed countries. iv In 2015, these were replaced by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that we are now aiming to achieve by 2030. These 17 goals have a similar aim as the MDGs but with a bigger focus on creating a sustainable future for everyone.

Despite working towards these goals, we-as a collective community-are allowing developing countries to suffer the worst hit from climate change. Not only this, but the climate crisis is reversing some of the progress that has been made in developing countries.

Generally, low-income countries are situated in warmer/ tropical parts of the world where there are higher risks of hurricanes, tsunamis, and cyclones. v This, coupled with economic hardship, can make preparation and recovery from severe weather very challenging, if possible at all. A reliance on natural resources for food, shelter, and overall livelihood is also common in developing countries. vi This further increases a country’s climate vulnerability, as natural resources–like crop harvests and sea life–are increasingly becoming destroyed and less available due to the effects of climate change. Haiti, Yemen, Sri Lanka, and Kiribati are just some of the places already suffering severe consequences of climate change. vii An inability to recover and prepare, coupled with the increasing and worsening effects of climate change, makes the future for developing countries very worrying.

In comparison, high-income countries tend to be in colder parts of the world, where warmer weather is welcomed. viii These countries are also far less vulnerable to extreme weather events like hurricanes, tsunamis, and cyclones, due to infrequent tropical weather. Therefore, low-income countries are considerably more vulnerable in the climate crisis.

Developing countries are clamouring to be heard by the rest of the international community, as they face the brunt of climate change. Kshenuka Senewiratne, a representative from Sri Lanka, spoke at the 74th General Assembly meeting in 2019, stating that “the looming threat of climate change has become an existential threat to several countries, including Sri Lanka, with its indiscriminate and unpredictable nature.” ix

To fix this crisis, the international community must pull together as a collective force to help support the most vulnerable. We cannot afford the devastating human cost of allowing developing countries to fall even further behind. Yet, BBC Environment correspondent Helen Briggs highlights how current policies are set to ‘push an additional 50 million people into poverty by 2030.’ x Therefore, our climate change policies must do more to prevent the gap between developing countries and developed countries becoming irreversibly–and devastatingly—unequal.

With the effects of climate change becoming increasingly worse, we must encourage and support policies that aim to eradicate these inequalities. This means ensuring that everyone has access to their essential needs such as food, housing, health, and energy supplies. xi Policies must act as a safety net for those who are most vulnerable to extreme weather events, and less able to respond and recover. We need to provide protection in high risk areas, and give low-income countries the means to be able to withstand the effects of climate change.

However, it is not just those in charge of policies that can do more to help developing countries. Anyone can help by donating to, or volunteering with, non-governmental organisations that are doing immeasurable work towards battling climate change. Global organisations like the Red Cross are providing climate disaster prevention worldwide. xii As well as, Amnesty International that fights for human rights protection within the climate crisis by holding governments accountable for their actions. xiii

Women and Climate Change

Of the 1.3 billion people living in poverty, 70% are women. xiv Women therefore represent the majority of world’s poorest people. xv

Poverty is a fundamental climate vulnerability. It means having a reliance on natural resources, which are increasingly becoming damaged by climate change. It also means that if your house is destroyed by extreme weather, you cannot rely on insurance or savings to recover. Or if your community is high risk to drought exposure, you need to travel to get water. These are just some of the social, economic, and cultural factors that make women predominantly more vulnerable to climate change than men. xvi

Globally, women have always faced serious gender inequalities. However, climate change is exacerbating this issue.

Action Aid notes that one of the reasons why these inequalities exist is because women ‘are less likely to be in positions of power and/ or decision-making roles.’ xvii It is this patriarchal power that is worsening the effects of climate change. Despite some women having leading roles and important voices in the fight for climate justice, they are still too often overlooked and missing from meaningful decision-making.

In their very important book, titled All We Can Save, Ayana E. Johnson and Katharine K. Wilkinson highlight how ‘women and girls are making enormous contributions to climate action: conducting research, cultivating solutions, creating campaign strategy, curating art exhibitions, crafting policy, composing literary works, charging forth in collective action, and more.’ xviii

With this in mind, it is critical that our climate action policies, responses, and strategies include and support women who represent a significant chunk of the victims affected by climate change. The involvement of women will not only increase the acknowledgement of the gendered nature of climate change, but it will offer new directions for climate action.

Environmental Racism

Environmental racism is described as ‘the unequal access to a clean environment and basic environment resources based on race.’ xix It subjects many individuals–that make up minority races–to increased climate vulnerability.

How can race affect someone’s ability to live in a healthy environment? It has already been mentioned that social and economic factors can determine one’s climate vulnerability. On a large scale, this can be seen in underdeveloped countries, but on a smaller scale, this can also be seen in deprived regions or areas of a country. Therefore, people who already face socioeconomic inequalities on a day-to-day basis are at a higher risk from climate change. xx

These socioeconomic inequalities become clear when we look at how close certain communities live to facilities that produce toxic waste. The majority of people that live within close proximity are those on a low-income. Examples of toxic facilities include ‘manufacturing, farming, water treatment systems, construction, automotive garages, laboratories, hospitals, and other industries.’ xxi Each of these pollutes the air and damage human and animal life.

The disproportionate effects of climate change are already causing generations’ worth of damage on human life. It is more than likely that they will cause premature deaths in communities that are within close proximity to toxic facilities. Due to socioeconomic inequalities, it is primarily ethnic minorities who live in these areas. It is not right that those who already suffer severe injustices within a society are also facing the brunt of a human-made crisis.

One group of people that suffers from environmental racism is Native American coastal tribes. Due to their close proximity to the ocean, they face some of the biggest risks from ocean acidification that damages animal and plant life. This happens when the ocean’s natural pH is lowered by rising levels of CO2... a detrimental consequence of climate change. xxii Communities such as these rely on natural resources for their survival and–without this–their livelihood is at risk.

The movement against environmental racism is not new. In the United States, it began in the 1970s and has since fought against this kind of systemic racism. xxiii It has been estimated that 75% of black Americans are more prone to live in areas close to gas and oil facilities. xxiv This is known to cause increased health risks and lead to fatal diseases like cancer and asthma. Data from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality shows that in 2016: per 100,000 kids, 223 black were admitted to the hospital for asthma, and 82 Hispanic, compared to 47 white. xxv

Environmental racism highlights a much deeper and alarming impact of climate change. We need to educate ourselves on this issue, and about the overall disproportionate effects of climate change. We need to fight the climate crisis as a collective, and we cannot do this when inequality continues to divide society.

Call To Action

Even the richest people in this world are not safe from climate change. Climate change affects every country and individual in the world. The issue is that it is not felt equally, and the most vulnerable people are–and will continue to–suffer the worst hit if we do not act now. The 10th Sustainable Development Goal is to reduce ‘inequalities based on income, sex, age, disability, sexual orientation, race, class, ethnicity, religion and opportunity’ by 2030. xxvi To achieve this, we need to not only recognise that climate change is worsening inequality, but use our policies and actions to acknowledge and stop the climate crisis.

The only reason that climate change discriminates is because human beings discriminate. Inequality is so deeply ingrained in our everyday living that it shapes further devastations, like the climate crisis. As human beings, we must come together to beat climate change.

We are the problem. And we are the solution.

Sarah Carter is the Human Rights and Climate Change Editor at Wandering Educators. She is currently studying a Master’s in Human Rights and Diplomacy at the University of Stirling. She is motivated by a desire to make a change in this world.

Endnotes:

i ‘Unprecedented Impacts of Climate Change Disproportionately Burdening Developing Countries, Delegate Stresses, as Second Committee Concludes General Debate’ GA/EF3516 (United Nations 2019) < https://www.un.org/press/en/2019/gaef3516.doc.htm > accessed 28 September 2021

ii Claire McGuigan, Rebecca Reynolds, Daniel Wiedmer ‘Poverty and Climate Change: Assessing Impacts in Developing Countries and the Initiatives of the International Community’ (Consultancy Project for The Overseas Development Institute, London School of Economics 2002)

iii ‘What is Climate Justice?’ (ClimateJust 2014) < https://www.climatejust.org.uk/what-climate-justice > accessed 24 September 2021

iv ‘The Millennium Development Goals Report 2015’ (UN.org 2015) < https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/2015_MDG_Report/pdf/MDG%202015%20rev%20(July%201).pdf > accessed 28 September 2021

v S. Nazrul Islam and John Winkel ‘Climate Change and Social Inequality’ (2017) Department of Economic & Social Affairs Working Paper ST/ESA/2017/DWP/152 < https://www.un.org/esa/desa/papers/2017/wp152_2017.pdf > accessed 28 September 2021

vi Tara Law ‘The Climate Crisis is Global but These 6 Places Face the Most Severe Consequences’ (TIME 2019) < https://time.com/5687470/cities-countries-most-affected-by-climate-change/ > accessed 29 September 2021

vii Ibid

viii S. Nazrul Islam and John Winkel ‘Climate Change and Social Inequality’ (2017) Department of Economic & Social Affairs Working Paper ST/ESA/2017/DWP/152 < https://www.un.org/esa/desa/papers/2017/wp152_2017.pdf > accessed 28 September 2021

ix ‘Unprecedented Impacts of Climate Change Disproportionately Burdening Developing Countries, Delegate Stresses, as Second Committee Concludes General Debate’ GA/EF/3516 (UN 2019) < https://www.un.org/press/en/2019/gaef3516.doc.htm > accessed 28 September 2021

x Helen Briggs ‘Carbon: How calls for climate justice are shaking the world’ BBC (2021) < https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-56941979 >

xi ‘What is Climate Justice?’ (ClimateJust 2014) < https://www.climatejust.org.uk/what-climate-justice > accessed 24 September 2021

xii ‘The climate crisis: why the world must act now’ (British Red Cross 2020) < https://www.redcross.org.uk/stories/disasters-and-emergencies/world/the-climate-crisis > accessed 5 October 2021

xiii ‘Climate Change’ (Amnesty International 2021) < https://www.amnesty.org/en/what-we-do/climate-change/ > accessed 5 October 2021

xiv Balgis Osman-Elasha ‘Women…In the Shadow of Climate Change’ (UN Chronicle) < https://www.un.org/en/chronicle/article/womenin-shadow-climate-change > accessed 28 September 2021

xv ibid

xvi ibid

xvii ‘Climate Change and Gender’ (Action Aid 2021) < https://www.actionaid.org.uk/our-work/emergencies-disasters-humanitarian-response/climate-change-and-gender > accessed 29 September 2021

xviii Ayana E. Johnson and Katharine K. Wilkinson All We Can Save: Truth, Courage, and Solutions for the Climate Crisis (One World 2020)

xix Aneesh Patnaik, Jiahn Son, Alice Feng, Crystal Ade ‘Racial Disparities and Climate Change (PSCI 2020) < https://psci.princeton.edu/tips/2020/8/15/racial-disparities-and-climate-change > accessed 30 September 2021

xx ibid

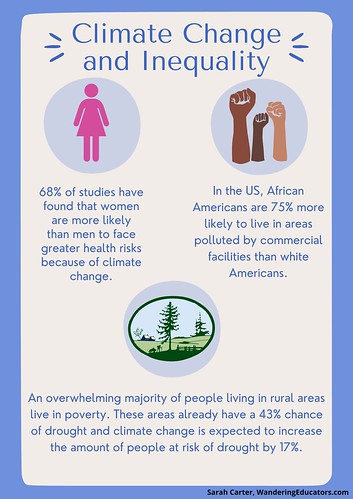

References for graphics:

Stat on women: Daisy Dunne ‘Mapped: How climate change disproportionately affects women’s health’ (Carbon Brief 2020) < https://www.carbonbrief.org/mapped-how-climate-change-disproportionately-affects-womens-health > accessed 28 September 2021

Stat on racial inequality: Aneesh Patnaik, Jiahn Son, Alice Feng, Crystal Ade ‘Racial Disparities and Climate Change’ (PSCI 2020) < https://psci.princeton.edu/tips/2020/8/15/racial-disparities-and-climate-change >

Accessed 28 September 2021

Stat on rural populations: S. Nazrul Islam and John Winkel ‘Climate Change and Social Inequality’ (2017) Department of Economic & Social Affairs Working Paper ST/ESA/2017/DWP/152 < https://www.un.org/esa/desa/papers/2017/wp152_2017.pdf > accessed 28 September 2021