Shipwrecks of the Great Lakes: The Milwaukee

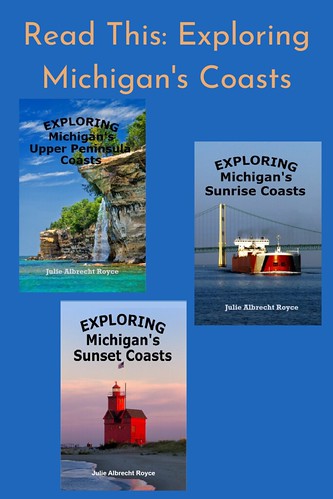

The approximate 6,000 ships that have succumbed to raging storms attest to the power of the Great Lakes. As I traveled, writing and compiling information for my three-volume travel series, Exploring Michigan's Coasts, I heard or read the tales left behind by those ill-fated ships. They add a somber, but compelling backdrop to Michigan’s waterways.

The train ferry Manistique-Marquette & Northern No. 1 was a train ferry built in 1903; in 1909 she was renamed Milwaukee

The Milwaukee’s captain, Robert McKay, recklessly ignored the second chance that luck graciously dealt him. The price tag for his ingratitude was his life. Fifty-two additional crew members went down with him. The man responsible for the foolhardy decisions of that dreadful night was alternately called a madman or dubbed “Heavy Weather McKay.” On October 22, 1929, he guided his 383-foot, railroad car ferry Milwaukee into the safety of the harbor for which she was named.

Rarely had a seasick crew been more relieved to step foot on solid ground than the men who had their queasy stomachs turned upside-down and knotted inside-out by a bullying storm. Bruising north winds had tried to take them under with every wave that washed over the deck on their way to port. But the crew emerged victorious.

Once they tied up in the harbor, the nauseated men, like the troopers they were, began pulling boxcars ashore. When the task was finished, twenty-five additional cars bound for the Grand Trunk Western’s rail station at Grand Haven stood waiting to be loaded onto the ferry for the return trip. The men again set directly to the task. Time was money, and car ferries never squandered either.

However, as the crew reloaded the Milwaukee, they must have considered the worsening weather, and hoped McKay would postpone the return trip long enough to let the storm abate. They knew better than to bet their paychecks on it. The Grand Trunk Western Railroad did not like to see their ships idle—storm or no storm—and this storm would be remembered as one of the worst to ever hit Lake Michigan.

With the final eastbound railcar loaded and in position, Captain McKay, to no one’s real surprise, announced his decision to depart immediately. Barely out of the harbor, the ferry was rocking and rolling. The captain of the lightship three miles from Milwaukee watched the ship bouncing east until the rain and spray enveloped her and then erased her from sight.

A second Grand Trunk Ferry departed Milwaukee four hours after Captain McKay. It reached the dock in Grand Haven on the morning of October 23, having staggered into harbor after a fifteen-hour battle with the killer storm. It had taken nine hours longer than usual to cross. The crew of the second ferry was surprised to learn McKay’s Milwaukee had not arrived before them. Everyone hoped she had been forced to abandon her normal course and sought shelter or turned north hoping for an easier trip.

The morning of October 24, Michigan and Wisconsin Coast Guard stations were alerted that the Milwaukee was long overdue. Debris was spotted floating in the water near Racine, Wisconsin, but it could not be definitively identified as wreckage from the missing Milwaukee.

On the morning of October 25, two bodies floated off Kenosha, Wisconsin, both wearing lifejackets from the Milwaukee. Bodies continued to roll in. The next day, a lifeboat was found, but the four crewmen inside were dead of hypothermia. A second lifeboat was found later in the day, but its canvas cover was still lashed in place, and no one was aboard. It was obvious the Milwaukee was lost.

The lifeboat from the shipwrecked SS Milwaukee train ferry, on display at the Port Washington (Wisconsin) Light Station. It was found with four dead occupants in lower Michigan

Grand Haven was home to thirty of the ferry’s crew, and the little community was devastated. Earlier that fall, on September 11, the Andaste had gone down in a storm while making its Grand Haven to Chicago run with a load of gravel. Thirteen of the twenty-five crewmembers who disappeared with the Andaste were also from Grand Haven.

Several days after the first bodies from the Milwaukee were found, a surfman at the South Haven station discovered her message case floating along the shore. Inside was a note signed by the ship’s purser: “S.S. Milwaukee, October 22, ’29, 8:30 p.m. This ship is taking water fast. We have turned around and headed for Milwaukee. Pumps are working, but sea gate is bent in and can’t keep the water out. Flicker is flooded. Seas are tremendous. Things look bad. Crew roll is about the same as on the last pay day.”

The note explained much of the mystery concerning the sinking of the Milwaukee. If the sea gate was damaged, there was nothing to stop water from flooding onto the main deck. The sea gate is a heavy steel gate that is dropped into place to close off the end of the main deck after the cargo of rail cars has been loaded. Without a functional sea gate, water would eventually fill the entire ship. Later investigation concluded that the sea gate may have broken when Captain McKay attempted to turn the ship around, perhaps causing one of the rail cars to come loose and crash into the gate. The flicker referenced the crews’ quarters that were located below the main deck near the stern of the ship. The purser mentioned the crew roll so the ship’s owners would know who had been aboard.

Later, a second note, sealed in a bottle, washed ashore. “This is the worst storm I have ever seen. Can’t stay up much longer. Hole in the side of the boat.” It was signed McKay. The note may have been a macabre joke. No one would ever know if there was a hole in the side of the Milwaukee, but it seems that if true, the purser’s entry would have mentioned it. It was suspected that the note was fake.

The anchor from the railroad car ferry S.S. Milwaukee. It was recovered by Roger Chapman in 1973 and donated to the City of Milwaukee.

The wreck, discovered in 1972, is located six miles north of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, off Whitefish Bay. Learn more: https://www.wisconsinshipwrecks.org/Vessel/Details/435

Click through to read excerpts from Royce's three books exploring Michigan's coasts:

Julie Albrecht Royce, the Michigan Editor for Wandering Educators recently published a three-book travel series exploring Michigan’s coastlines. Nearly two decades ago, she published two traditional travel books, but found they were quickly outdated. This most recent project focuses on providing travelers with interesting background for the places they plan to visit. Royce has published two novels: Ardent Spirit, historical fiction inspired by the true story of Odawa-French Fur Trader, Magdelaine La Framboise, and PILZ, a legal thriller which drew on her experiences as a First Assistant Attorney General for the State of Michigan. She has written magazine and newspaper articles, and had several short stories included in anthologies. All books available on Amazon.

Help promote Michigan. Books available on Amazon.

All photos in the public domain, via Wikimedia Commons